Originally published on Memorial Day 2023.

Memorial Day grew out of the Civil War, from the formal and informal remembrances by veterans and widows in both North and South for the young men who paid the ultimate price in America’s bloodiest and most personal conflict.

It is hard to imagine today, but the reconciliation between North and South after the war was unique in history. Men who were killing each other in 1863 were able to shake hands in brotherhood fifty years later.

Isn’t it fascinating to see how the men who actually fought the Civil War bore each other much less ill will than do today’s activists and agitators? America has never fought a more determined enemy than herself, but the two sides came together over the proceeding half century to build the greatest and most powerful nation in the history of the world. By the time the last Civil War veterans had passed away, the matter of the war was considered settled. The North got what it wanted – the Union was maintained and slavery abolished – while the South had the freedom to honor its heroes and wax nostalgic about the lost cause.

Today, that reconciliation is being erased in the name of a new civic religion based on grievances and victimhood which is passionately promoted in many cases by people who have no historical connection to the Civil War themselves. Confederate statues have been torn down, military bases named for Confederate generals have been renamed, bodies have been exhumed, and the Battle Flag – once a symbol of Southern pride – has been effectively banned. This iconoclasm dishonors the dead on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line.

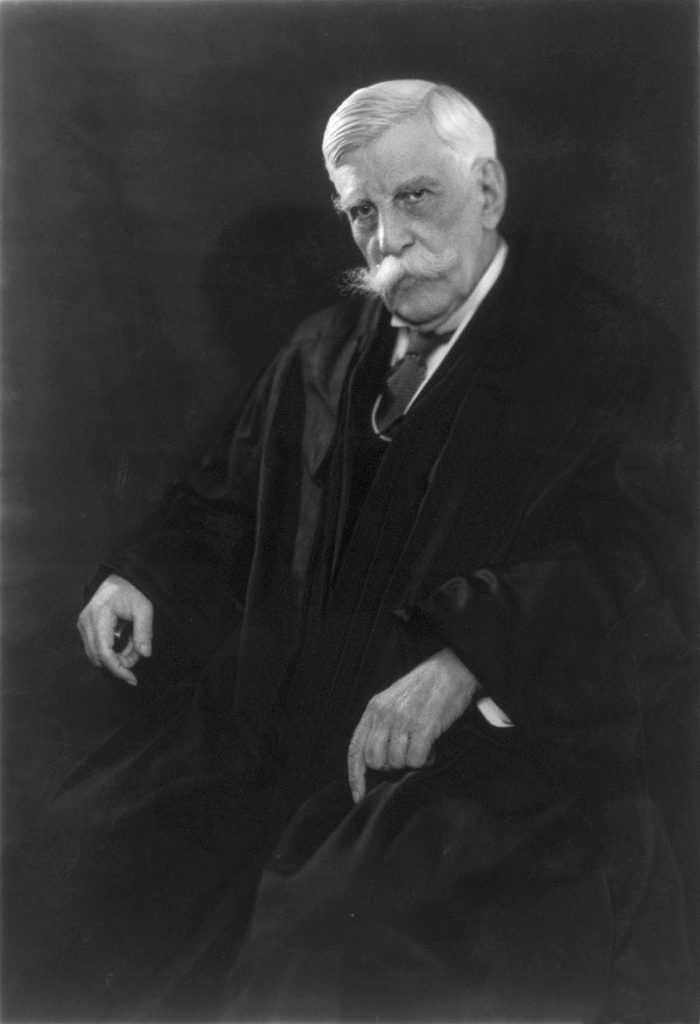

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was wounded three times during his service in the Union Army. He would later go on to be one of our most prominent Supreme Court justices and his writings on American jurisprudence are still routinely cited today. In 1884, nearly two decades after the end of the Civil War, Holmes gave an address to John Sedgwick Post No. 4 of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization of Union veterans.

The premise of his speech was an answer a hypothetical question: why do we still celebrate Memorial Day? Rather than re-litigating the causes of the war, Holmes recognized that the men who fought for both the North and the South did so for what were to them good reasons:

The soldiers who were doing their best to kill one another felt less of personal hostility, I am very certain, than some who were not imperiled by their mutual endeavors…

We believed that it was most desirable that the North should win; we believed in the principle that the Union is indissoluble; we, or many of us at least, also believed that the conflict was inevitable, and that slavery had lasted long enough. But we equally believed that those who stood against us held just as sacred conviction that were the opposite of ours, and we respected them as every men with a heart must respect those who give all for their belief.

Holmes went on to answer the question he posed at the beginning of his speech:

So to the indifferent inquirer who asks why Memorial Day is still kept up we may answer, it celebrates and solemnly reaffirms from year to year a national act of enthusiasm and faith. It embodies in the most impressive form our belief that to act with enthusiasm and faith is the condition of acting greatly. To fight out a war, you must believe something and want something with all your might. So must you do to carry anything else to an end worth reaching. More than that, you must be willing to commit yourself to a course, perhaps a long and hard one, without being able to foresee exactly where you will come out. All that is required of you is that you should go somewhither as hard as ever you can. The rest belongs to fate.

After spending some time remembering some of the men he knew who fell in battle, and remarking on the friendships that are forged in the fires of war, Holmes struck at the heart of the matter:

But, nevertheless, the generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing. While we are permitted to scorn nothing but indifference, and do not pretend to undervalue the worldly rewards of ambition, we have seen with our own eyes, beyond and above the gold fields, the snowy heights of honor, and it is for us to bear the report to those who come after us. But, above all, we have learned that whether a man accepts from Fortune her spade, and will look downward and dig, or from Aspiration her axe and cord, and will scale the ice, the one and only success which it is his to command is to bring to his work a mighty heart.

Everybody knows that the purpose of Memorial Day is to remember those who died in service to our country, but there is a deeper meaning as well, something that Oliver Wendell Holmes understood nearly 150 years ago. There is no way for those who served in combat to fully convey that experience to those who did not, but days like today serve to impart a sense of solemn gravity to those who follow behind. As Holmes said that day:

Feeling begets feeling, and great feeling begets great feeling. We can hardly share the emotions that make this day to us the most sacred day of the year, and embody them in ceremonial pomp, without in some degree imparting them to those who come after us. I believe from the bottom of my heart that our memorial halls and statues and tablets, the tattered flags of our regiments gathered in the Statehouses, are worth more to our young men by way of chastening and inspiration than the monuments of another hundred years of peaceful life could be.

It is easy for us to sit in our comfortable chairs and debate the merits of this or that conflict. I think history clearly shows that most of America’s wars since 1945 were unnecessary, but that need not cheapen the sacrifices made by American soldiers. They fought for country, for honor, for God, and for their friends, and that should be sufficient. It is not the heads of state and diplomats that we remember, but the soldier doing his duty to the ultimate end. “We in it shall be remembered,” said Shakespeare’s Henry V, stirring your soul no matter your opinion about the utility of the Battle of Agincourt. “They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old,” wrote Laurence Binyon, and this remains true whatever your thoughts on the First World War.

In 1863, with the outcome of the Civil War still in doubt, President Abraham Lincoln visited the Gettysburg battlefield and said, “…we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.”

War has been part of the human condition since the dawn of time, and will surely always be so. We lament war as the destruction of human lives and livelihoods, yet we honor those who fight, because they exhibit the best of human nature: courage, bravery, honor, and self-sacrifice. More than a million young Americans gave their lives in conflicts from Lexington to Fallujah, and each one deserves to be remembered. The stripes on our flag are dyed with their very blood.

But grief is not the end of all. I seem to hear the funeral march become a paean. I see beyond the forest the moving banners of a hidden column. Our dead brothers still live for us, and bid us think of life, not death–of life to which in their youth they lent the passion and joy of the spring. As I listen, the great chorus of life and joy begins again, and amid the awful orchestra of seen and unseen powers and destinies of good and evil our trumpets sound once more a note of daring, hope, and will.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. – May 30, 1884

If you live in the Treasure Valley, stop by the Eagle Field of Honor at Merrill Park. Each flag represents someone who served our country, someone dear to those who remain today.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.

One Comment

Comments are closed.