At the start of his great book Rubicon: The Last Days of the Roman Republic, popular historian Tom Holland presented two seemingly contradictory quotes:

Human nature is universally imbued with a desire for liberty, and a hatred for servitude.

Caesar, Gallic Wars

Only a few prefer liberty—the majority seek nothing more than fair masters.

Sallust, Histories

Julius Caesar’s quote came in the context of the stories he sent home from Gaul to maintain support and popularity while he was away from Rome. They were the 1st-century BC equivalent of our modern political campaigns, in which Caesar bypassed the political establishment—by then hostile to him—and appealed directly to the people. Think President Donald Trump using Twitter to bypass the legacy media.

Sallust, on the other hand, was a supporter of Caesar’s but far more cynical at heart. Like many Roman historians, he looked back with nostalgia at a mythical golden age that ended before he was born, decrying the corruption and decay of his own generation. It’s fair to say Sallust did not have a high view of his contemporaries. Think of the constantly complaining blackpillers on social media.

The Roman people famously hated kings. After throwing off the Etruscan Tarquin dynasty five centuries before the birth of Christ, “king” became a dirty word in Rome. The ideal Roman was not power-hungry or ambitious, but rather like Cincinnatus—who took on dictatorial powers reluctantly and surrendered them as soon as possible.

Yet there is something in human nature that desires a strongman who can Do What Needs To Be Done. The same Romans who abhorred monarchy loved Caesar, who essentially operated as a king without the title. Shakespeare dramatizes a moment in which Mark Antony offers Caesar a laurel crown, only for him to reject it, prompting cheers from the crowd.

Caesar was a populist, using his power to give the people what they wanted—and in doing so, securing his own. In hindsight, it seems obvious that Caesar’s populism led inexorably to autocracy. His successor, Octavian Augustus, did not claim the title of king or even emperor—he called himself princeps, the first citizen of Rome. It wasn’t until three centuries later that Diocletian finally dropped the pretense.

Contrary to his own quote, Caesar’s actions resembled Sallust’s observation about human nature. He understood that most Romans in the 1st century BC were less interested in participating in the Republic than in simply living their lives. Politics can be all-consuming, and a republic—the res publica, or public business—only works if everyone participates. Isn’t it easier to let someone else worry about politics while you tend your garden?

Americans hate kings too. Rejection of monarchy is woven into our founding mythology just as it was in ancient Rome. Our Founding Fathers threw off the tyranny of King George III, George Washington refused a crown, and—as Benjamin Franklin supposedly said—we were given a republic, if we could keep it.

Yet human nature is what it is. Figures like Henry David Thoreau, prototype of the modern libertarian who just wants to be left alone, have always been the exception. We remember Abraham Lincoln as one of our greatest presidents, even though (or despite?) he arrested journalists and lawmakers, suspended habeas corpus without Congress, and called up volunteers to prosecute an undeclared war. He transgressed the bounds of the Republic in order to save it. History looks far more kindly on him than on his predecessor, James Buchanan, who refused to act for fear of violating the Constitution.

In his First Inaugural Address, Franklin D. Roosevelt laid out an ambitious plan to combat the Great Depression, one that vastly expanded federal power. He warned that if Congress failed to pass his agenda, he would ask for essentially dictatorial authority:

But in the event that the Congress shall fail to take one of these two courses, and in the event that the national emergency is still critical, I shall not evade the clear course of duty that will then confront me. I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis–broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.

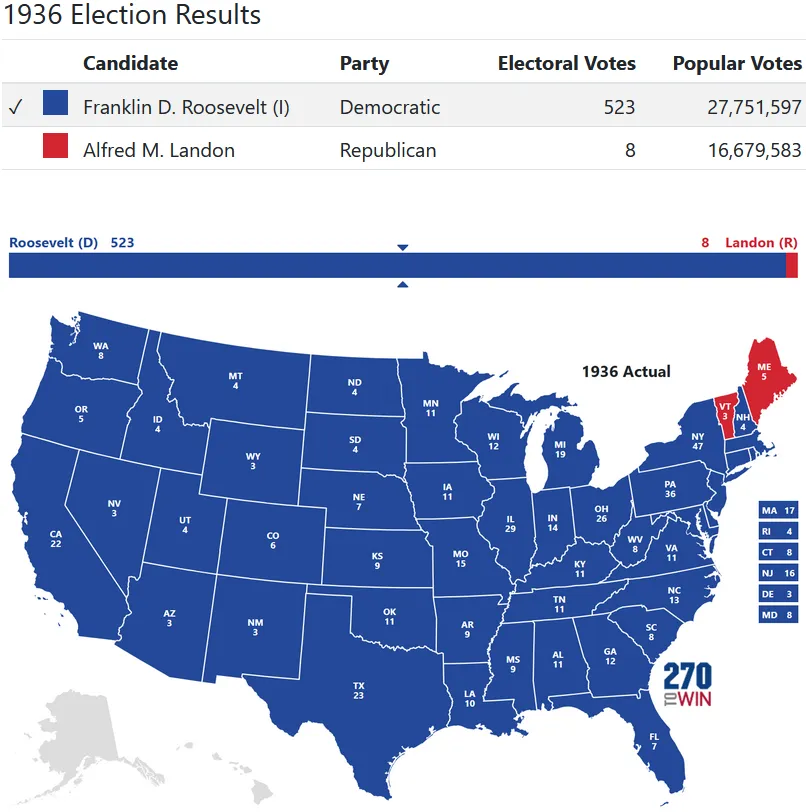

Notice the applause when FDR called for emergency powers. Had he outright declared himself a king, the American people wouldn’t have stood for it. Even before his inauguration, rumors of a coup by military and business leaders shook the nation. Yet like the Romans of Caesar’s day, Americans in the 1930s loved a leader who Did What Needed To Be Done without the kingly title. No matter how often Republicans explained that Roosevelt was far beyond precedent, or how the economy still had not recovered by the late 1930s, the American people adored him. Not only was Roosevelt reelected three more times—every election was a landslide.

Ask yourself which head of state had more direct power over his nation in the summer of 1933: President Roosevelt, or Britain’s King George V?

Americans hate kings, but we tend to love kingly figures. During the Barack Obama administration, I recall Democrats fervently wishing he would ignore Congress, ignore the courts, and just do what they wanted. Obama leaned into that sentiment, echoing FDR when confronted with a Republican Congress:

We are not just going to be waiting for legislation in order to make sure that we’re providing Americans the kind of help that they need. I’ve got a pen, and I’ve got a phone. And I can use that pen to sign executive orders and take executive actions and administrative actions that move the ball forward in helping to make sure our kids are getting the best education possible, making sure that our businesses are getting the kind of support and help they need to grow and advance, to make sure that people are getting the skills that they need to get those jobs that our businesses are creating.

Many supporters of President Trump feel the same way. If Congress can’t, or won’t, act, then the president should. The post-FDR federal government has its fingers in so many pies that modern presidents have tremendous and far-reaching authority. Trump can decide which foreigners are allowed in, DEI and transgender policies in education, the existence of USAID programs, and even what tariffs to levy against foreign importers (pending a Supreme Court decision). Who has more day-to-day power over his country today: President Trump, or Britain’s King Charles III?

Now I’m sure you’re thinking this doesn’t apply to you, that you’re a firm believer in republican government and just as uneasy about Trump’s expanding power as you were about Obama’s. Yet even liberty-minded conservatives betray a desire for a good guy to step in and Do What Needs To Be Done. How many social media posts demand that Someone Just Do Something? The Legislature is spending too much—it should just cut the budget. I don’t like what the governor is doing—we should just elect a new one. The federal government is corrupt—we should just hold them accountable.

Twitter user Devon Eriksen put it well:

“I have a plan for GoodThing!”

“Great, let’s hear it.”

“First of all, everybody has to just —”

“Okay, pump the brakes, there, smart guy. How do you plan to get people to just?”

“Well, they should just —”

“Perhaps, but how are you going to get them to just?”

“They should!”

“They will not. They will not just. Never in the history of humanity have they just.

The whole tweet is worth reading. Whether you’re at a computer or standing on a street corner, demanding that Someone Just Do Something is the perspective of a subject, not a citizen. Subjects beg their kings; citizens of a republic have the responsibility of governing themselves.

Say what you will about the Star Wars prequels, but George Lucas hid some interesting philosophical debates beneath the hammy acting and flashy action:

ANAKIN: I don’t think the system works.

PADME: How would you have it work?

ANAKIN: We need a system where the politicians sit down and discuss the problems, agree what’s in the best interests of all the people, and then do it.

PADME: That is exactly what we do. The trouble is that people don’t always agree. In fact, they hardly ever do.

ANAKIN: Then they should be made to.

PADME: By whom? Who’s going to make them?

ANAKIN: I don’t know. Someone.

PADME: You?

ANAKIN: Of course not me.

PADME: But someone.

ANAKIN: Someone wise.

PADME: That sounds an awful lot like a dictatorship to me.

If you’ve read this far and think I’m advocating for monarchy, you’re not paying attention. I believe the American Republic is the greatest form of government ever created by man, but it requires citizens to participate, not spectate.

Citizenship carries responsibilities. I often think about Theodore Roosevelt’s 1910 speech at the Sorbonne, in which the former president explained to young French aristocrats what it meant to be a citizen of a republic:

A democratic republic such as ours—an effort to realize in its full sense government by, of, and for the people—represents the most gigantic of all possible social experiments, the one fraught with great responsibilities alike for good and evil. The success of republics like yours and like ours means the glory, and our failure the despair, of mankind; and for you and for us the question of the quality of the individual citizen is supreme… With you here, and with us in my own home, in the long run, success or failure will be conditioned upon the way in which the average man, the average woman, does his or her duty, first in the ordinary, every-day affairs of life, and next in those great occasional cries which call for heroic virtues. The average citizen must be a good citizen if our republics are to succeed.

I posted a deep dive into this speech and why I believe it is so important last spring:

We take for granted the difference between subjects and citizens. If we were subjects of a benevolent monarch, we could safely ignore the world of politics, leaving that to the king and his advisors. What a relief that might be—not having to worry about what our government is doing. But for citizens, tasked with the awesome responsibility of self-government, disengagement is not an option. Every one of us must not only govern ourselves, but take part in the great discourse of republican service.

The great and terrible irony is that if citizens of a republic do not fulfill their responsibilities—if they sit back and complain, demanding Someone Just Do Something—then eventually someone will. Caesar became dictator for life, transforming the Roman Republic into an Empire with enthusiastic popular support. Napoleon ended the chaos of the French Revolution and, for a time, became master of Europe. Hitler was the democratically elected chancellor of a dysfunctional republic before consolidating power, again with popular support.

Those examples show the inherent danger of a populist dictator. The Bible records God’s warning to Israel when they demanded a king:

So Samuel told all the words of the Lord to the people who were asking for a king from him. He said, “These will be the ways of the king who will reign over you: he will take your sons and appoint them to his chariots and to be his horsemen and to run before his chariots. And he will appoint for himself commanders of thousands and commanders of fifties, and some to plow his ground and to reap his harvest, and to make his implements of war and the equipment of his chariots. He will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers. He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive orchards and give them to his servants. He will take the tenth of your grain and of your vineyards and give it to his officers and to his servants. He will take your male servants and female servants and the best of your young men and your donkeys, and put them to his work. He will take the tenth of your flocks, and you shall be his slaves. And in that day you will cry out because of your king, whom you have chosen for yourselves, but the Lord will not answer you in that day.”

1 Samuel 8:10-18

Populist dictators carry the seeds of destruction for themselves and their nations. All three mentioned above met ignoble ends—Caesar was assassinated by Roman senators, Napoleon died in exile, and Hitler committed suicide as his enemies closed in, his name to live forever as the personification of pure evil.

But that is our future if we don’t fulfill our responsibility as citizens of the American Republic. Auron MacIntyre laid it out in a column earlier this month:

When legislative bodies fail, bureaucracies grow unchallengeable, and moneyed elites block ordinary people from their own society, Spengler argued that a Caesar figure reliably emerges — a leader who sweeps aside gridlock and imposes order. Not necessarily a tyrant in the cartoonish sense, but a figure who commands enough power to break the stalemate.

The danger is obvious: Once such a leader accumulates that power, nothing guarantees he gives it back. Caesar may save the nation, transform it, or accelerate its decline. What is certain is that once he arrives, the political order changes rapidly.

Auron went on to say that Donald Trump is not Caesar, but could be a precursor, just as Lucius Cornelius Sulla foreshadowed Julius Caesar. Sulla believed that the reforms of his rival Gaius Marius went too far, so he took action to save his beloved Republic. He marched on Rome with an army, forced the Senate to name him dictator, purged Marius’ supporters, and then retired to his villa, believing his work finished.

Caesar, then a teenager, watched, learned, and awaited his moment. The Republic was already over, but nobody knew it yet.

The question we face today is how to avoid the same fate. If an American Caesar comes, it will not be in the form of a mustache-twirling villain, but a populist who pledges to Do What Needs To Be Done without regard for the law or precedent. A critical mass of the American people will celebrate the moment, not condemn it. How, then, can we maintain the American Republic amid massive and rapid changes in technology, geopolitics, demographics, and a global economy?

MacIntyre’s follow-up column addressed the demographic issue especially:

The phrase “self-governing” can mislead because it suggests isolated, autonomous individuals. That is not what classical thinkers meant. A republic needs the lightest touch of any governmental form because the community reinforces itself. Citizens hold each other to account.

From Aristotle to Machiavelli to the American founders, the assumption was the same: A republic requires a virtuous people bound by thick ties of identity and shared moral expectations. Formal authority exists, but most of the real enforcement happens through custom and communal pressure, with the civil magistrate stepping in only when necessary. A republic works only when its people possess enough virtue and cohesion to govern themselves.

Our future is in our hands. We must relearn the lessons Theodore Roosevelt taught at the Sorbonne. We must reclaim our birthright as American citizens. We must fulfill our responsibilities to our nation and our communities.

That is why I do what I do. The purpose of the Gem State Chronicle is to empower you to make positive change in Idaho by giving you the tools to be engaged citizens of a republic rather than subjects spectating on the sidelines. I’m not here to tell you what to think or to drive you to outrage in hopes you’ll sign a petition or send me money. If you like what I’m doing, I’m grateful for your support, but you’ll notice that I rarely put anything behind a paywall. Everything on Idaho Insider is available for free because I believe in the mission. Citizenship in our Republic is not reserved for those with money—even just $9.99 per month—but is the birthright of every American.

Article I, Section 2 of the Idaho Constitution clearly explains our role in government:

All political power is inherent in the people. Government is instituted for their equal protection and benefit, and they have the right to alter, reform or abolish the same whenever they may deem it necessary

Voting, attending town halls, speaking to your representatives, donating to candidates, knocking on your neighbors’ doors, and standing for elected office—these are not privileges. They are responsibilities belonging to every citizen. The future belongs to those who show up. If you’re sitting on the couch tweeting that Someone Should Just Do Something, beware: someone will—and you might not like the result.

The American people face the same choice as did the people of Rome in the time of Sulla and Marius, Caesar and Sallust: do we step up and reclaim our Republic, or do we sit back and let a strongman take care of everything? Be careful what you wish for. Stop waiting for someone to step up, and realize that you are that someone. You are a citizen of the greatest nation in the history of the world, and it’s your responsibility to pass it on to your posterity.

“A republic, if you can keep it,” goes the saying. That’s the question—will you and I keep our Republic?

Feature image screenshot from video by KTVB.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.