During the 2025 Idaho GOP Winter Meeting, delegates debated Resolution 2025-2, which called for each county in Idaho to be represented by one senator in the Legislature. I stood up and debated against the resolution, pointing out, among other concerns, that a single senator could not properly represent the 525,000 people living in Ada County.

This did not endear me to delegates from rural counties, who have long supported this idea. I promised I would research the issue and share my findings. As I prepare for the Idaho GOP Summer Meeting beginning this Friday, that day has finally come. While I appreciate the passion of the idea’s supporters and the desire for stronger representation in government, I ultimately find myself in the same position I was six months ago. Let’s examine the issue in depth together.

The debate over how best to represent the people in government is an old one. It came to a head during the Philadelphia Convention, where delegates from the thirteen states gathered to replace the Articles of Confederation with a new constitution.

Under the Articles, all thirteen states had equal representation in Congress, with each state’s delegation casting a single vote. The Convention itself used the same structure: one vote per state delegation. Yet the weaknesses of that system had been revealed during the 1770s, and the delegates were open to new ideas.

Edmund Randolph of Virginia proposed a bicameral legislature, with both houses representing the states proportionally. Delegates from smaller states balked, fearing they would be constantly outvoted by the larger ones. William Paterson of New Jersey countered with a unicameral legislature, similar to the existing Congress, in which each state had equal representation.

James Madison and Alexander Hamilton initially supported the Virginia Plan. Madison believed that even the larger states would rarely unite enough to overpower the smaller ones, while Hamilton argued that state borders weren’t particularly important and that the United States should be a single, unified nation. But the Convention reached a deadlock as smaller states refused to support a proportional legislature.

To make a long story short, the delegates settled on a compromise: a new government with an upper chamber—the Senate—with equal representation for each state, and a lower chamber—the House—with proportional representation. The Senate would confirm treaties and presidential appointments, while all spending bills would originate in the House. Senate terms were six years, compared to two years in the House. The result was a Senate that tended to be slower and more conservative, and a House that was more populist.

This structure has worked fairly well for our country ever since. The 17th Amendment, ratified in 1913, made senators directly elected rather than appointed by state legislatures, but equal representation in the Senate remained constant. In fact, Article V of the Constitution forbids any amendment that would deprive a state of its equal vote in the Senate.

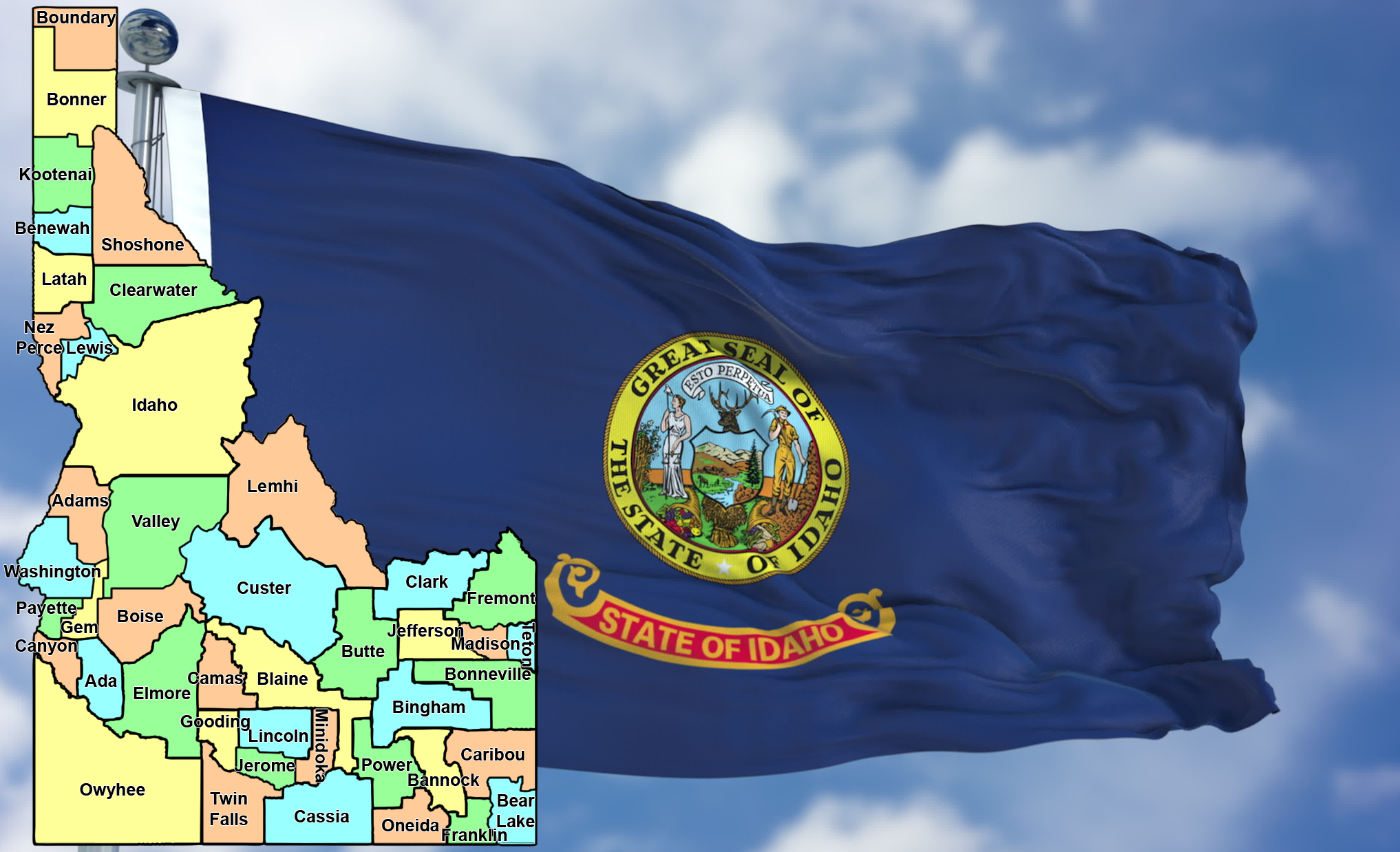

Many states, Idaho included, initially followed the federal model. Upon achieving statehood in 1890, Idaho had 18 counties, each of which was represented by one senator. The House was somewhat proportional, with more populous counties receiving multiple representatives.

In 1964, however, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 8-1 in Reynolds v. Sims that such systems violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote that “legislators represent people, not trees or acres.” Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented, arguing that the 14th Amendment did not govern how states apportioned their legislatures.

In response, Sen. Everett Dirksen of Illinois proposed a constitutional amendment to allow states to continue using equal representation by geography, but the amendment failed in Congress.

Idaho, along with the rest of the states still using the old system, changed to district-based representation. Today, Idaho consists of 35 legislative districts (the maximum allowed by the state constitution), each with approximately 52,546 residents. That number is changed every ten years after the census, with district boundaries redrawn to maintain equal representation. Some geographically large districts, such as LD7 and LD8, span multiple rural counties. Ada County, on the other hand, contains all or part of eleven legislative districts.

That’s how we got here. So what should we do now?

Rural Idahoans are understandably frustrated with the current system. Clark County, the least populous in the state, with only 801 people, is part of LD31 along with Fremont, Jefferson, and Lemhi Counties. All three legislators from LD31—Reps. Jerald Raymond and Rod Furniss, and Sen. Van Burtenshaw—are from Jefferson, the most populous of the four counties.

You can see why a resident of Clark County—or of Lemhi or Fremont, for that matter—might feel underrepresented. Many such residents have been trying for years to do something about it.

A few years ago, the late Charles Lee Barron of Camas County wrote an essay calling for a return to what he called “a republican form of government” for Idaho. He claimed the Virginia Plan proposed at the Philadelphia Convention would have led to tyranny:

The Madison/Randolph plan was a disguised form of democracy… one man, one vote. Democracy works in small venues where the participants are trying to achieve a common goal because of the comity of mutual endeavor. But it is always a form of tyranny, for one side gets everything and the other nothing.

Barron denounced Reynolds as well:

A particularly Socialistic Supreme Court made up of 9 un-elected lawyers, cherry picking through the 14th Amendment, found a hidden meaning in that amendment that allowed the Federal Court to reapportion state legislatures along the lines of the Madison/Randolph proposal. An outcome totally repugnant to the written Constitution.

He proposed a constitutional amendment to return Idaho to a system in which each county has one senator and at least one representative. He said it was necessary to prevent Idaho from devolving into a “tyranny of the majority” where “Ada and Canyon counties run the state.”

Barron’s proposed amendment never saw legislative action, and he unfortunately passed away in 2022. Others have picked up the torch, with Owyhee County GOP chairwoman Tammy Payne submitting Resolution 2025-2 at this year’s Winter Meeting:

WHEREAS; Article 4 Section 4 of The United States Constitution States, states “The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government…”

WHEREAS; The Framers of said Constitution, gave an example through The US Constitution, as to what a properly formed Republic should look like.

WHEREAS; Article 2 Section 3 Of the US Constitution states, “The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State…”

WHEREAS; the purpose of Article 2 Section 3 was to give each State equal representation regardless of population, protecting the more agrarian States from urban rule.

WHEREAS; the current fashion The State of Idaho elects its senators, better resembles a representative democracy, than a republic.

WHEREAS; The State of Idaho has had heavy growth in its urban centers, largely from out of state

WHEREAS; Residents of each county in Idaho have a better understanding, of their culture, economy, natural resources, and strengths and weaknesses, than do urban residents in other parts of the state.

THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, the Idaho Republican State Central Committee recommends that following the example of the US Constitution Article 2 Section 3, that the State of Idaho should have one (1) senator from each county, regardless of population.

The resolution passed, despite my objections, but no action was taken in the Legislature this year.

Before considering the merits of the idea, let us evaluate what it would actually take to return to the pre-Reynolds method of apportionment.

Article III, Section 2 of the Idaho Constitution restricts the number of senators to equal to the number of districts, which is 35. Representatives are fixed at twice the number of senators. Returning to one senator per county would therefore require a constitutional amendment.

The proposed amendment would need to be passed in the form of a joint resolution by 2/3 of both the House and the Senate. That’s already a tall order, especially on the Senate side where only 12 members are needed to kill such a resolution. How many senators would be willing to vote themselves out of a job? With 14 senators between Ada and Canyon Counties alone, all but two of whom would be out of office should this idea come to fruition, it is not likely to pass the Senate floor.

If it somehow passed, the amendment would then need approval by a majority of Idaho voters. Given that over one million residents live in the state’s four largest counties (Ada, Canyon, Kootenai, and Bonneville), it’s unlikely that a majority would vote to reduce their own representation.

Yet even if the measure passed, courts would almost certainly strike it down, since the Supreme Court has already ruled on this issue. While that isn’t necessarily a reason not to pursue it—after all, Idaho recently passed a law reinstating the death penalty for child sex abusers despite prior rulings—it does mean the state would face a lengthy and costly legal battle with very low odds of success.

Is it worth diverting the time and energy of the attorney general and his staff to fight this battle? Even after everything else, the Supreme Court could simply refuse to grant certiorari and all that hard work would be for naught.

To me, that alone suggests this should not be a top priority. But even beyond that, we must ask: is this proposal the right idea? The problem that this idea is attempting to solve is a lack of representation from rural counties. However, it begs the question: should the 801 residents of Clark County have the same representation in the Idaho Senate as the 524,673 in Ada?

There are several assumptions made by supporters of this idea—the “whereas” clauses of the resolution—that deserve scrutiny.

First, the idea assumes that each state should resemble the nation. The states of the early Republic had various ways of apportioning representation, with some having one senator per county, others per town, while others used proportional representation. Following the ratification of the Constitution, many states adopted a similar structure: an upper chamber with equal representation based on geography and a lower chamber with proportional representation based on districts.

However, this again begs the question: are states republics in their own right? Whereas the states themselves were sovereign entities that came together to form the federal government, counties are different. Counties are political subdivisions of the state. Owyhee County is the oldest county in Idaho, organized by the territorial legislature in December 1863. It did not predate the Idaho Territory itself. Several other counties were partitioned over the next few years, including Ada, which was created out of a portion of Boise County.

Statehood came about through the actions of the people and their representatives in the territorial legislature, not the counties. Or, to put it another way, the federal government is a compact between sovereign states, while the state government is a compact by the people of the state. It has nothing to do with counties.

The 10th Amendment guarantees that all powers not explicitly granted to the federal government in the Constitution are reserved to the states or to the people. There is no such guarantee for counties within states. Counties are entirely subordinate to states.

Counties are defined in Article XVIII of the Idaho Constitution, which goes into great detail about their structure and responsibilities—even specifying how county officials must be paid. There is nothing like this in the federal Constitution. Article IV, while outlining certain rights and responsibilities of the states, does not micromanage their internal affairs, because the Framers believed that states had the inherent right to govern themselves.

States are sovereign political entities that voluntarily cede some of their inherent authority to the federal government, while retaining all powers not explicitly delegated by the Constitution. Counties, by contrast—like cities, towns, and special taxing districts—are subdivisions of the state. They are not sovereign entities in their own right but derive their authority entirely from state law.

Article IV, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution says:

The United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government.

A “republican form of government” means several things:

- Government by elected representatives: neither monarchy or direct democracy

- Popular sovereignty: power derives from the people

- Rule of law, with constitutions limiting government power

- No hereditary rule, aristocracy, or dictatorship

- A system that reflects the consent of the governed

It does not necessarily follow that a republican form of government requires a bicameral legislature in which one chamber is apportioned equally by certain political boundaries. Republics throughout history have had a variety of forms of representation. For example, the Most Serene Republic of Venice, which existed for more than a thousand years, restricted voting rights to patrician families, which essentially meant that membership in the Senate or Great Council was hereditary. Even the early American Republic restricted voting to white male landowners, a sort of patrician class in and of itself.

In my opinion, returning to a pre-Reynolds system of representation is neither practical nor historically defensible. I understand this may be frustrating for those who feel strongly about the idea, but I can only follow where the facts lead. That brings us to a third, critical question: would this change even accomplish what its supporters hope it would?

The purpose of returning to pre-1964 apportionment would be to gain more representation for rural counties, as opposed to more populous counties such as Ada, Canyon, Kootenai, and Bonneville. Another assumption made in the “whereas” clauses of this year’s resolution is that senators from big cities not only wield disproportionate power in the Legislature, but they vote against the interests of rural areas. I’m not sure that’s true.

Idaho remains a very rural state. Of the 234 198 incorporated cities, only the top three have populations over 100,000. Only the top fourteen even have populations over 20,000.

Of the 44 counties in Idaho, the top four have populations over 100,000. The median is between Franklin and Fremont Counties, which have 14,000 and 15,000 residents respectively.

This means that despite the Treasure Valley being the obvious population center, the rest of the population is pretty widely distributed.

The current Speaker of the House is Rep. Mike Moyle, who hails from Star. With just over 16,000 residents, Star is the 19th largest city in Idaho, nestled between Chubbuck and Jerome in population size. Just a few years ago, it had only a few thousand residents. Is it fair to say that Star is punching above its weight by being the hometown of the Speaker of the House?

The current President Pro Tempore of the Senate is Sen. Kelly Anthon, who lives in Burley—the 23rd largest city in Idaho—and was raised in Declo, which ranks 160th. Burley spans Cassia and Minidoka Counties, the 15th and 18th most populous counties in the state, respectively. Even combined, they have fewer residents than the city of Twin Falls.

Even Gov. Brad Little serves as a counterexample, as he lives in Emmett—the 29th largest city in the state. Emmett is the county seat and only incorporated city in Gem County, which ranks 19th in population with just over 21,000 residents.

I think rural Idaho has representation in our government, though perhaps not sort of representation that some would wish.

The idea that urban senators would band together to vote against the interests of rural citizens does not bear scrutiny either. Consider the senators who currently represent all or part of Ada County: Tammy Nichols, Scott Grow, Codi Galloway, Ali Rabe, Carrie Semmelroth, Janie Ward-Engelking, Melissa Wintrow, Josh Keyser, Treg Bernt, Lori Den Hartog, and Todd Lakey. If you follow Idaho politics, you know there is a wide variety of ideological viewpoints spanning those eleven names. The idea that they would work together to deprive rural Idahoans of their rights doesn’t hold water.

Speaking of water, that is an area that has seen much debate over the past year, especially centering around the needs of ground water users in eastern Idaho and surface water users in southern Idaho. Yet even legislators whose districts are not as reliant on these systems were able to come together and do what was best for everyone. Politics is not always a zero-sum game.

Lava Ridge is another strong example. Although the proposed wind farm site spanned Jerome, Lincoln, and Minidoka Counties—the 16th, 37th, and 18th most populous in the state—Idahoans from across the political and geographic spectrum came together in opposition. If the assumptions behind Resolution 2025-2 were taken to their logical conclusion, one might expect political figures from outside the Magic Valley to show little concern for Lava Ridge. But that wasn’t the case.

Would switching to the pre-Reynolds system change the ideological makeup of the Legislature? Currently, there are five Democrats in the Idaho Senate—the four representing Boise plus Sen. James Ruchti from Pocatello. Moving to county-based representation could potentially reduce that number to two, since only Blaine and Teton Counties voted for Kamala Harris in the 2024 election. Of course, local elections often have their own dynamics, so the exact outcome is difficult to predict.

It’s also difficult to make an apples-to-apples comparison of counties and their ideological leanings over time. For example, 1964—the year of the Reynolds v. Sims decision—was the last time Idaho supported a Democrat for president: Lyndon B. Johnson. Ironically, Ada County voted for Barry Goldwater that year.

In any case, the question that many proponents of this idea are really asking is can we elect more conservatives to the Legislature? Would switching from districts to counties make the Idaho Senate more conservative, or less?

Measuring degrees of conservatism is challenging, as people have different definitions of what it means. Predicting how representation might shift if senators were elected by county rather than by district is even harder. Using the Idaho Freedom Foundation’s Freedom Index as a guide, 10 senators fall within the top quintile (80%-100%), 12 in the 60%-80% range, 7 between 40%-60%, and the five Democrats score between 20% and 40%.

Switching to county-based representation would eliminate quite a few of these senators. For example, Canyon County would have to choose just one out of Sens. Tammy Nichols, Camille Blaylock, Ben Adams, and Brian Lenney. On the other hand, Sen. Christy Zito from LD8 would be limited to representing just Elmore County, leaving Boise, Custer, and Valley Counties needing to elect new senators. I’m not sure there are many who would be more conservative than Zito.

Returning to the Freedom Index, the five lowest-scoring Republicans are from the counties of Bingham, Bonner, Jefferson, Bonneville, and Bannock. Those range from the 4th largest (Bonneville) to the 12th largest (Jefferson). Returning to a pre-Reynolds system would mean those five would likely still represent their counties, while Boundary, Butte, Clark, Fremont, and Lemhi would elect their own senators. There’s no guarantee that they would be more conservative than their current legislators, but it’s possible.

Beyond constitutional questions, there are numerous logistical issues with the idea to return to county-based representation. Right now, each state legislator represents a district of approximately 52,000 people, whether it be confined to a few city blocks like LD20 in Meridian or spanning hundreds of miles from Oregon to Montana in LD7. Switching to county-based representation would mean that a single senator would be required to represent the more than half a million residents of Ada County all by him or herself.

Prior to Reynolds, the smallest Idaho county, Clark, consisted of only 915 people, while the largest, Ada, had a population of 93,460. That’s a ratio greater than 102:1. Today, Ada County is home to 524,673 people, compared to Clark’s 801, for a ratio of 655:1. That means that if we switched to a county-based system, one Clark County resident would have 655 times more representation in the Senate than his Ada counterpart.

Does that sound like representative government?

While this argument resembles those proffered by leftists who oppose the U.S. Senate and the Electoral College, remember that these are two very different situations. States hold on to a measure of sovereignty within the federal union, while counties are simply political subdivisions of each state.

The resolution also claims that county residents are better equipped to understand their own counties than urban dwellers (many of whom, according to the resolution, come from out of state). Yet isn’t the converse true as well? Switching to a county-based system means that the senators representing the 23 least-populous counties would constitute a Senate majority despite representing less than 10% of Idaho’s population. There are churches larger than the population of Clark County.

To sum up the three reasons I believe this should not be a priority for Idaho Republicans:

- The cost and effort required are too high, with a very low chance of success.

- The idea doesn’t align with the historical foundations of America or Idaho.

- I’m not convinced it would actually increase rural representation or make Idaho more conservative.

After the 2025 Winter Meeting, I promised to research this issue and share what I learned. I know it is surely disappointing that my position hasn’t changed, but I must follow where the facts lead. It would have been easy to simply agree for the sake of approval, but that’s not how I operate. I’m not married to this position; like many others in this space, I want what’s best for the people of Idaho, whatever that may be. I deeply respect those who hold opposing views and hope this doesn’t cause any rifts. Wise people can agree to disagree.

Rather than pursuing a questionable plan that has a very low chance of political success, I believe that our finite time and resources would be better spent reaching out to voters in rural counties and bringing them into the process. The right candidate can win even if they live in a small county—Rep. Faye Thompson lives in Valley County, which is 27th largest by population, yet she defeated incumbent Megan Blanksma from Elmore County, which is 13th.

Our current system is not perfect, but I believe it reasonably represents the people of Idaho. That said, I understand the concerns motivating proponents of the Idaho Republic idea. I humbly suggest that we focus our time, energy, and resources on solutions that will yield a far better return than trying to overturn 60 years of precedent and case law. We are already making meaningful progress in making Idaho a friendlier place for faith, family, and freedom. Now is not the time to lose momentum by chasing what I believe is a costly and distracting red herring.

I wrote a short bonus note for paid subscribers. Click over to Substack to check it out. Don’t know what I’m talking about? Consider supporting the Gem State Chronicle by becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.