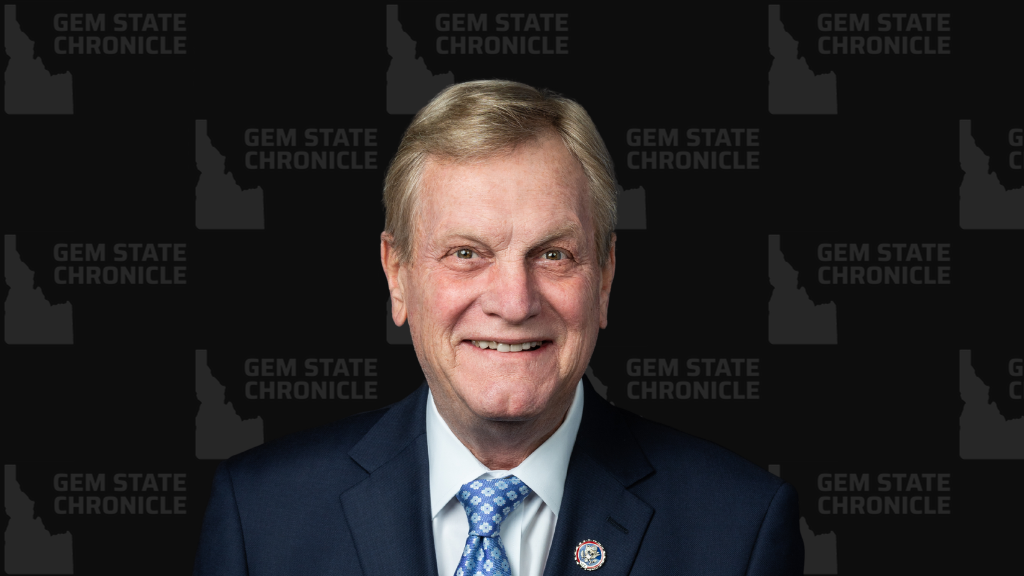

By Sen. Brian Lenney

Last week, we on the Idaho Senate Health and Welfare Committee buried House Bill 131 (H 131) after the House shoved it through 53-17.

The idea was to Label every blood donation by mRNA COVID-19 vaccination status—Pfizer or Moderna shots—so recipients know what’s flowing into their veins. Transparency’s a great goal; and I wanted this to work.

But after two hours of testimony, we saw the truth: this bill was scientifically impossible as well as an interstate disaster waiting to happen.

The Science Says No: No Test Can Reliably Identify mRNA-Vaccinated Blood

Let’s start with the fact that there’s no reliable, rapid blood test to confirm if someone’s had an mRNA COVID shot, especially not long after the jab. H 131 needed that certainty to work.

It didn’t exist, and testimony made that painfully clear.

The mRNA itself—lipid nanoparticles in Pfizer’s BNT162b2 or Moderna’s shots—tells cells to churn out SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, then breaks down fast. A 2022 study out of Denmark used quantitative PCR (qPCR) to track it in blood, finding synthetic mRNA detectable for up to 15 days post-vaccination, max. After that, enzymes shred it—gone.

No rapid test, like a fingerstick lateral flow assay, can spot it months or years later. Even qPCR, a lab-only method needing hours and specialized gear, can’t help at donation scale—Idaho’s blood banks process ~50,000 units yearly, and we’re not hauling DNA sequencers to every site.

What about the spike protein it produces? Typically, it’s short-lived. A 2023 study using proteomic mass spectrometry caught recombinant spike protein in vaccinated blood, but only for days to a couple weeks.

Another paper with ultrasensitive single-molecule assays found it in plasma up to 15 days post-shot, then it clears out—metabolized or flushed. Some labs, like Germany’s INMODIA GmbH, offer spike detection in blood or tissue, but it’s not rapid—it’s a mail-in, wait-for-results process.

Blood banks need answers now, not next week.

Testimony drilled this in: no point-of-care spike test exists, period.

Yale’s latest, from a February 19, 2025, report, threw a curveball (someone just sent this to me)—Akiko Iwasaki’s team found “elevated levels” of spike protein in some folks with post-vaccination syndrome (PVS), alongside immune shifts like lower CD4 T-cells and higher inflammatory markers.

But it’s no game-changer. It’s a small study—60 people, preprint, not peer-reviewed—focused on chronic symptoms, not every vaccinated donor. They don’t say how long spike lasts or why it’s there, and it’s not a rapid test we could use. It’s not a smoking gun, and nowhere near ready for H 131’s demands.

Then there’s antibodies—the closest we’ve got. Rapid tests, like JOYSBIO’s 25-minute kit, use a fingerstick to detect anti-spike IgG antibodies, which mRNA vaccines induce.

Sounds workable… until you unpack it.

SARS-CoV-2 infection also triggers anti-spike antibodies, so a positive doesn’t prove vaccination.

Experts suggested a workaround: pair it with a nucleocapsid antibody test. mRNA shots don’t code for nucleocapsid protein—only infection does. So, anti-spike positive and nucleocapsid negative might mean vaccinated, not infected.

But it’s a house of cards. Antibody levels drop over time—studies show anti-spike IgG waning in months to years, depending on the person. Nucleocapsid antibodies fade too, especially post-mild infection.

Bottom-line: a blood donor vaccinated in 2021 could test negative now; an infected one might lack nucleocapsid markers later. False negatives, false positives—it’s a mess. No antibody combo guarantees a vax label long-term. The Yale data only deepens the doubt—if spike’s lingering unpredictably, antibodies might not even match up.

Nail in the Coffin: Interstate Blood Flow

But even if we ignored or even SOLVED the test problem, H 131 would’ve imploded the moment blood crossed state lines.

I learned that Idaho’s plugged into a national blood grid—Red Cross, America’s Blood Centers—moving units to Washington, Utah, Montana, and back. Testimony laid out the numbers: 20-30% of our ~50,000 annual units go interstate. Hospitals here lean on that flow; rural ones especially need hubs like Seattle for rare types.

If we’d passed H 131, every Idaho donation would’ve needed a vax label.

No other state does this—none.

Our blood, tagged “vaccinated” or “unvaccinated,” would hit a wall out-of-state. Places like Oregon or Wyoming don’t track vax status, don’t care, and don’t have systems to handle our quirky labels. They’d reject our units as non-standard—red blood cells spoil in 42 days, platelets in 5, so delays kill supply.

Flip it around: their unlabeled blood rolls into Idaho, and H 131 says we can’t use it without testing every drop. But with no rapid test (see above), we’d be stuck—retest with slow lab methods or toss it. Either way, 5,000-7,500 units could vanish yearly, gutting our stockpile.

Donors travel too—Idahoans hit Spokane, Washington folks donate in Boise.

H 131 wouldn’t bind out-of-state sites, so an Idahoan’s donation there comes back unlabeled, unusable here. In-state travelers self-report? Sure, but memory fails, and some lie. Without a test to verify, it’s chaos. Testimony showed us a disaster scenario: a wildfire or crash, and Montana’s emergency blood sits at the border, rejected over label fights, while our rural hospitals bleed dry.

The FDA’s another snag—they oversee blood nationally, and vax status isn’t on their radar. Idaho going rogue could’ve lost us accreditation, cutting federal ties. Costs—millions for testing, tracking, lost units—would’ve crushed a system already down 10-15% in donors since COVID.

We couldn’t risk that.

Two hours of this—scientists, blood bank reps, hard stats—convinced us: H 131 was a good idea that wouldn’t work in the real world. No test can tag mRNA-vaxed blood with certainty, and interstate flow can’t survive a lone state’s rule.

We killed it to protect Idaho’s supply, full-stop.

Originally published at Brian Lenney (Nampa’s Senator) 3/10/25

About Brian Lenney

Brian Lenney represents District 13 and the city of Nampa in the Idaho State Senate. A Nampa resident since 2010, he lives there with his family and enjoys fishing in Idaho’s outdoors. He is also the author of two books: "Why Everyone Needs an AR-15! A Guide for Kids" and "Why is Feminism So Silly? A Guide for Kids".