By Julianne Young

After four months of intense deliberation, on September 15, 1787, the Founders were engaged in a final review of the draft. The stakes were extraordinarily high. Consensus was critical to avoid the collapse of the fledgling nation into political chaos.

According to James Madison’s notes, Article V of the draft at that time stated:

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem necessary, or on the application of two thirds of the Legislatures of the several States shall propose amendments to this Constitution . . .

Upon review of Article V, Colonel George Mason and Elbridge Gerry, both staunch Anti-Federalists, raised concerns. These men consistently opposed consolidating power at the federal level and sought to limit federal authority wherever possible. Colonel Mason argued that granting Congress exclusive authority to propose amendments was unwise, that an “oppressive government” could refuse to propose amendments.

Misrepresenting the Convention Clause

Modern convention advocates distort Mason’s concerns, claiming the Article V convention mechanism was designed as a remedy for an “oppressive government.” While Mason did voice concerns about government overreach, his argument was specific to Congress’s potential reluctance to propose amendments—not a general safeguard against federal tyranny. The Founders relied on impeachment, elections, and the Constitution’s checks and balances to address abuses of power, not an amendment convention.

Following Mason’s remarks, Gerry and Gouverneur Morris proposed an amendment to Article V requiring Congress to “call a convention to propose amendments” upon the states’ request. Madison expressed mild reservations, questioning why Congress wouldn’t be equally bound to propose amendments as to call a convention. However, he ultimately had “no objection… against providing for a convention for the purpose of amendments,” though he did note concerns about potential difficulties regarding quorum and procedural matters.

The inclusion of this convention mechanism was not a centerpiece of Constitutional design or an intentional safeguard against an overreaching federal government. Instead, it was a last-minute compromise suggested by an opponent of the Constitution and accepted with little debate in an environment where concerns were noted, but overshadowed by a broader desire to build consensus at a critical moment in time.

The Founders’ True View on Conventions

Convention proponents ignore critical context from that same day’s debates. Mason and Gerry, having just influenced the addition of the convention mechanism, immediately proposed convening another full Constitutional Convention. Mason warned of an impending monarchy or aristocracy and insisted that a second convention, informed by the people’s will, would produce a system more aligned with their interests. He objected to presenting the Constitution as a “take it or leave it” decision.

This idea was swiftly and forcefully rejected. Thomas Pinckney warned that calling another convention would lead to confusion and discord, with delegates reflecting their states’ competing interests rather than reaching consensus. “Conventions are serious matters and should not be repeated,” he emphasized. While he personally objected to some provisions in the Constitution, he preferred to accept them rather than risk “the sword” — a clear reference to potential national instability and conflict.

Madison’s notes record a unanimous vote against a second convention — with Mason and Gerry apparently outvoted within their own state delegations. Ultimately, Colonel Mason and Mr. Gerry would be two of only three delegates that did not sign the final Constitution. Over the next two days, as the remaining delegates signed the Constitution, they emphasized the urgent need for unity and the danger of reopening fundamental debates. Their collective wisdom has now blessed Americans for nearly a quarter of a millennium. The Constitution they signed has proved to be a wise and sound foundation for the most prosperous, free nation in the world.

The Danger of Misrepresenting the Founders’ Intent

Claiming that the Founders intended future generations to use the Article V convention process as a safeguard against “out-of-control” federal government is an egregious distortion of history. While they were willing to include the “convention” method in a spirit of compromise as a means to address perceived “defects,” the record plainly shows that the primary advocates of the convention mechanism were men opposed to the Constitution itself — while the vast majority of delegates recognized and sought to avoid the dangers inherent in conventions.

Having risked their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor to secure independence and national unity, the Founders knew the immense cost of the Constitution they crafted, and they approached the question of conventions with great caution. Surely, they would expect no less caution of us. Rather than risk it all based on a false narrative, let us safeguard and enforce it.

Source: The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Volume 2 (Scroll to Madison’s notes from September 15, 1787.)

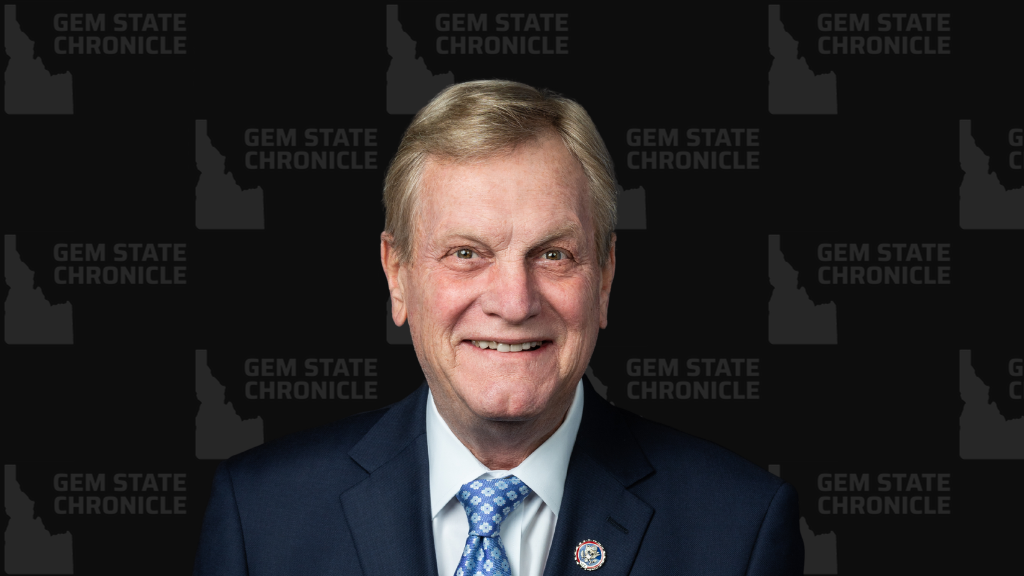

About Julianne Young

Julianne Young served three terms in the Idaho House of Representatives. She and her husband Kevin live in Blackfoot and have ten children. She currently sits on the board of Idaho Family Strong.