By Rick Hogaboam

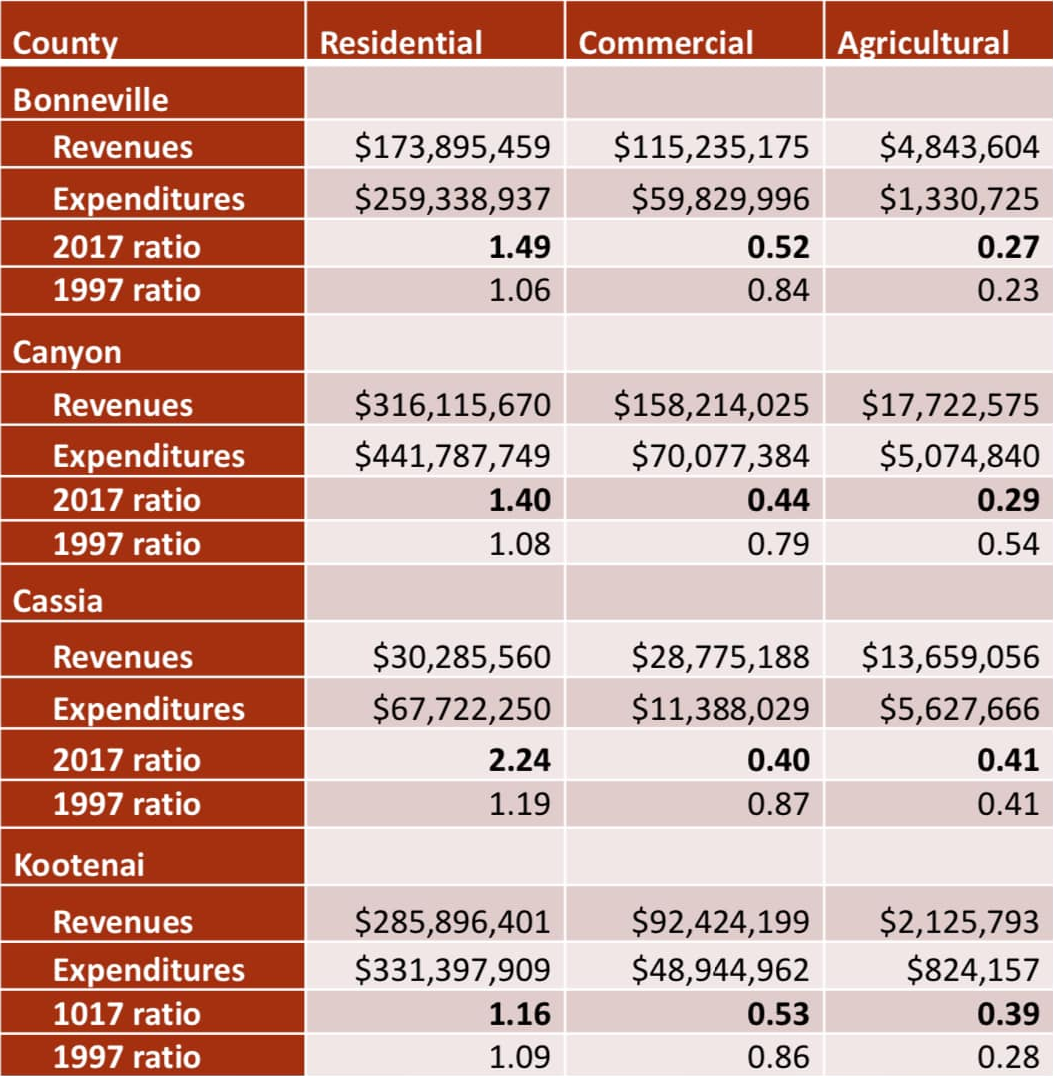

We need an updated report showing the revenue versus cost of service ratios for various classes of property. When agricultural land converts to rooftops, the costs for providing services exceed the revenue generated from residential taxes. Of course people need rooftops to live, but these ratios will create insolvency and/or reduction in level of service. Market forces may very well push a community to approve nothing but rooftops, but such a community will soon realize that it can’t provide all the expected services, leading to cuts and diminished quality of life.

“But growth is adding revenue,” proponents state; yes, and also creating the need for more infrastructure and personnel. When the infrastructure and personnel are not added in proportion to the new growth, the overall level of service is partially diminished. Compound this effect over years and decades and it will certainly be felt. And the more we find “outside” funding at the federal or state level, the more it perpetuates an illusion of wealth and solvency, but that asset is also depreciating (and a future liability) with a replacement cost in the future that may not be covered by the outside revenue source. Who’s responsible? The recipient who couldn’t afford the thing to begin with. And how are they going to fund replacement and significant capital maintenance? Bonds? And if that doesn’t work? Well, that thing will likely not be replaced or simply phase out of existence. End result? Community is either ponying up more revenue via additional taxes or suffering the loss of a once valuable asset that it perceived as being able to afford. In some cases, such pruning may actually reveal that the costly thing wasn’t as needed as once thought. Communities grow rapidly, building lots of shiny stuff, and then fast forward, that same community has to make some difficult decisions about what’s worth keeping as cost of maintenance and replacement exceed budget capacity to sustain. A hard reality sets in. And you don’t have the luxury of turning back the clock and making different decisions.

The temptation is grow, grow, grow, because the new revenue becomes, in part, a way to fund existing liabilities. But that should be a clue not all is well. Rather than solving the problem, this pattern can actually exasperate the problem.

All of this is compounded by the fact that the conversion from productive agricultural land to residential use creates a service cost in excess of the increased tax revenue, in the net aggregate, in general. Of course factors like arterial access and infill versus sprawl all play significant factors in a thoughtful cost of service analysis. People also need homes. And if the market-driven demand for new homes is organically fueled, then it is merely a reflection of the local economy creating more employees who need places to live. But, when the demand side is inflated by an influx of prospective residents who don’t have a local job, then that inflationary demand creates some challenging dynamics, namely the inflation of homes beyond local wage growth, which pressures the locals. So the default answer is to build more homes, and quickly, but this market-driven instinct may perpetuate a problem more than it solves.

Of course there are property rights, but such rights exist within the framework of prudent land use decisions, always mindful that growth should not diminish the level of service for the existing population nor create a subsidized liability to be paid by the existing base. Why have land use law at all if “free market” means the right to do and build anything anywhere at anytime at any cost to the existing community in shared (or exasperated) use of existing infrastructure? Thankfully, our land use law allows for prudence to mitigate against decisions that would negatively affect the community.

Many communities have sprawled into a state of insolvency. The replacement costs on existing infrastructure far exceed budget capacity, necessitating bonds for replacement, let alone new capital. This is where a community descends into the death spiral, where ever-increasing debt that can’t be adequately funded when bonds are rejected require the scaling back of services and the inevitable decline of the quality of life in said community. Everything from schools to the courthouse to the jail are affected, and it’s possible to exasperate the ability to provide essential mandated services while having no mechanism for funding costly new capital projects fueled by growth. Impact fees may help the growth increment, but they aren’t in place for schools and not implemented for jails. What this means is that growth eventually creates a tipping point where expansion is needed, and who gets to fund that expansion? The community at large.

We need to seriously question the cost of growth and ensure that it doesn’t compromise our existing quality of life and proportionate cost of service model. Until mechanisms are in place to ensure responsible growth and long-term solvency, I’m afraid we’re just intoxicated in a growth pattern with a false illusion that it’ll all work out. We must do better or else we will look back on this time as a case study of reckless growth without proper mitigation policies in place to ensure the ability to sustain critical infrastructure.

Originally published on Facebook. For more information visit the research paper titled “Costs of Community Services – Idaho Counties Redux” by Allan Walburger of BYU-Idaho.

About Rick Hogaboam

Rick Hogaboam a husband, father, and the current Canyon County Clerk. He previously served as Chief of Staff for the City of Nampa. He is focused on election integrity, fiscal stewardship, transparency, efficient court administration, & accurate record-keeping and processing.