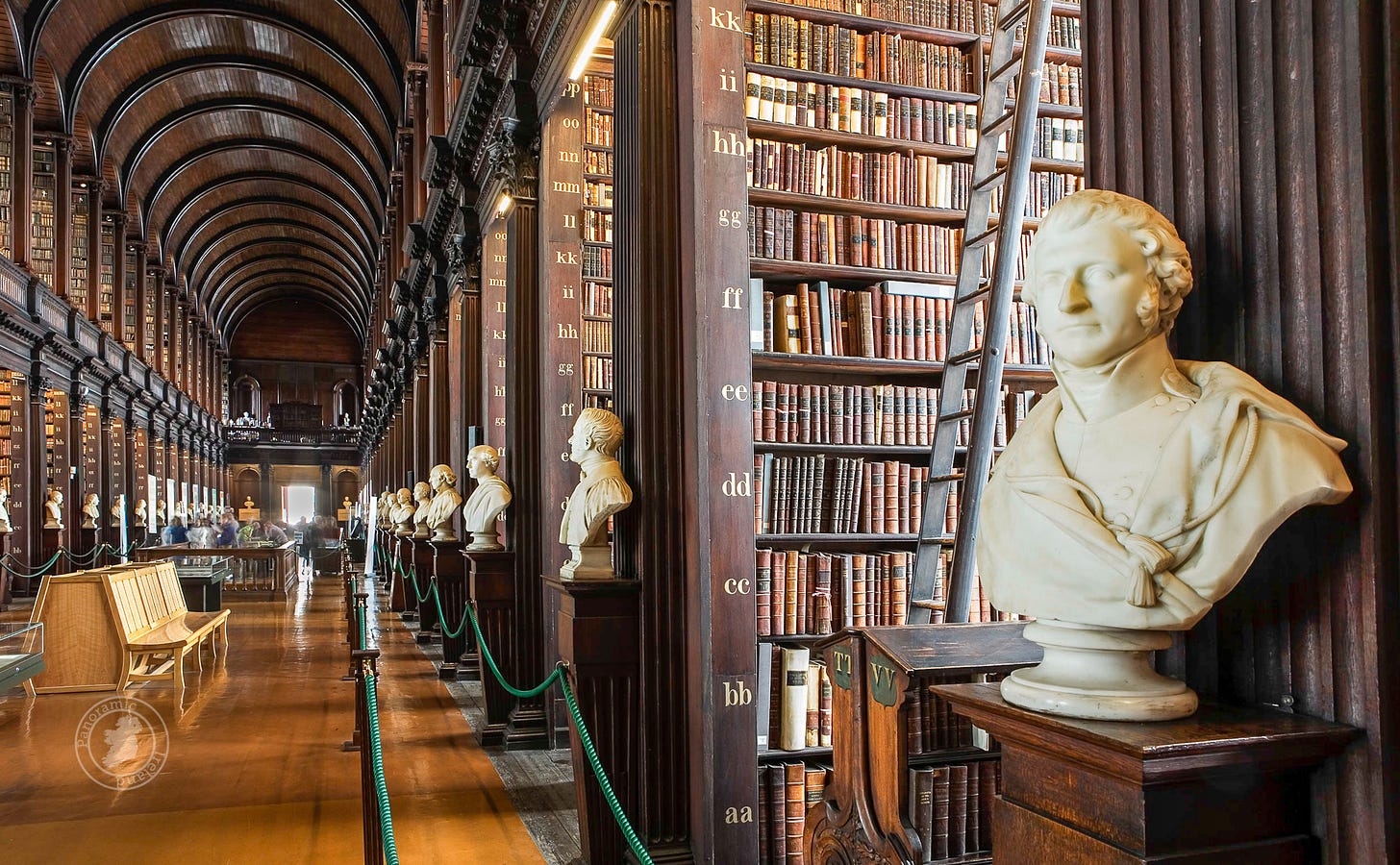

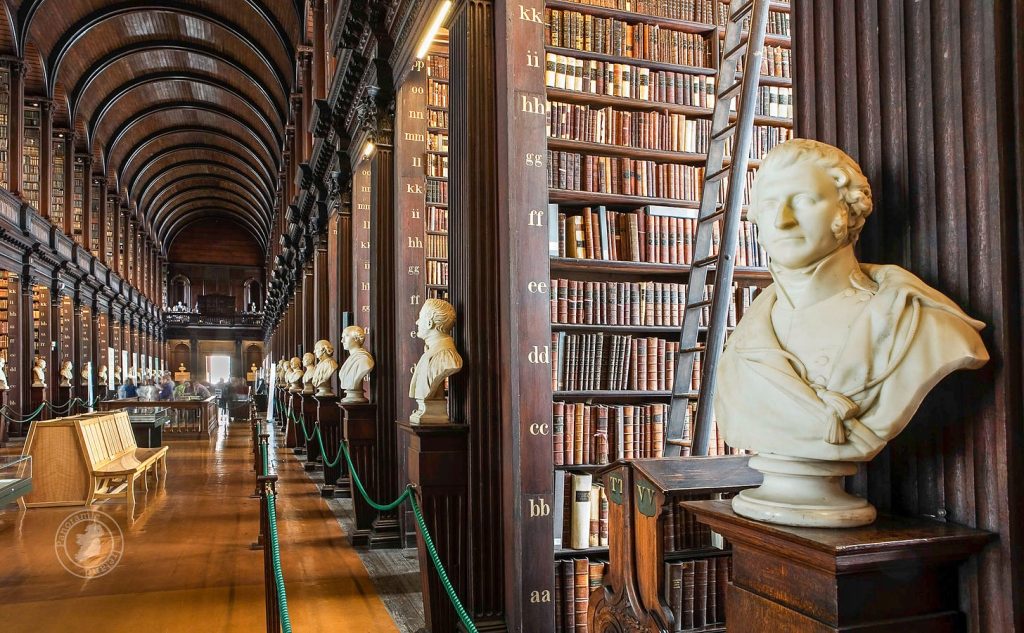

Ever since human beings began using the written word, we have used libraries to house the knowledge of our civilizations. There is evidence of proto-libraries in the ruins of Sumeria dating back to 3,400 BC, and the Hittites and the Assyrians built depositories for the written word in antiquity as well. The Great Library of Alexandria was begun in the 3rd century before Christ by Ptolemy II and served as a repository of all known knowledge for many years. The library of Trinity College, Dublin, was established in 1592 and to this day carries a copy of every work published in Ireland.

Some of the earliest public libraries in America were established by the Anglican Church in the early 18th century. Charitable societies connected to the church took donations to operate free public libraries in the colonies, such as the one at Old State House in Boston that was destroyed by fire in 1747.

In 1731, Benjamin Franklin and some others founded the Library Society of Philadelphia, which sold shares to citizens who then had the right to check out books. The Library Society still operates as a nonprofit to this day.

The Library of Congress was founded in 1800, and its collection replenished after the burning of the White House during the War of 1812 from Thomas Jefferson’s private collection. To this day it remains the official depository of knowledge in America, containing two copies of every copyrighted work in the nation.

Industrialist Andrew Carnegie famously used his massive fortune to establish free public libraries throughout America and the world starting in the late 19th century. Many libraries got their start through donations from wealthy benefactors, and the architectural grandeur of these buildings was the gift of these benefactors to their communities.

Even today, wealthy benefactors fund library buildings or renovations in exchange for recognition. I have a distant cousin who donated nearly half a million dollars to the Anaheim Public Library, and the children’s wing now bears her name. The Eagle Public Library’s new Family Place Space was sponsored by Valnova, the new housing development in the northwest corner of the city.

Free and public libraries sprang up wherever Americans gathered. Along with churches, schools, and taverns, the presence of a library demonstrated the reach of civilization. That every city and town in America should have a free public library supported by taxpayers is the sort of progressive idea that we all take for granted today. Our great-grandparents generation assumed that having books and reference materials available for all citizens would naturally result in a more educated society.

Are free public libraries still necessary to fulfill that mission?

Today, most Americans have access to the internet, which brings to our fingertips more information than Ptolemy or Jefferson could ever have imagined. The entire contents of college history courses are available alongside videos of silly cats — our problem today is not access to information, but too much information.

The Eagle Public Library, of which I am a trustee, stocks approximately 57,000 books. A large number of those are checked out at any given time. In August 2024, the last month for which I have data, 26,936 children’s books were checked out along with 1,528 teen books and 16,060 adult books. An additional 16,104 digital items licensed by the Eagle Public Library were checked out by residents as well.

The Eagle Public Library Board of Trustees voted in September to relocate 25 books — 22 from the teen section to the adult shelves, and 3 off the floor entirely, to be replaced with “dummy” books that still allow patrons to check them out, as many places still do with DVDs and video games.

This decision has led to a lot of chatter in the media. Everyone is waiting to see how House Bill 710 affects the status quo, as many members of our communities have called for measures to prevent minors from accessing books with inappropriate imagery and descriptions. Eagle’s is the biggest relocation yet, and I’ve been contact by numerous members of the media to explain why we did what we did.

Brian Holmes of KTVB, who aired a hit piece against me when I was initially appointed to the board two years ago, decided to follow up last week. While Aspen Shumpert, the reporter who recorded the interview, was evenhanded with her questions, Holmes couldn’t resist being his snarky self, suggesting that I was on a crusade to remove LGBTQ+ materials:

I wrote before my appointment to the board that libraries, as public institutions, should reflect the values of the communities they serve, and that Christian and conservative members of those communities must step up if they are to maintain those values. I believe that organizations such as the American Library Association (ALA) have taken an explicitly hostile position toward such values, and are actively using the library to get between parents and children. That is a major reason why I voted earlier this summer to remove various statements from the ALA from the Eagle Public Library policies and mission statement.

Nevertheless, Eagle has a very nice library. It’s free from some of the overt leftist proselytizing that you see in Meridian and Boise, and unlike big-city libraries throughout the country, it has not been turned into an encampment for the homeless and mentally ill. Nevertheless, does the library still serve a purpose in 21st century life that justifies the cost to taxpayers?

Wayne Hoffman, founder and former president of the Idaho Freedom Foundation, wrote an article last week about the controversy over inappropriate books. He suggested that we’re missing a larger issue:

Here’s where I take issue with the law and others like it across the country: There are an estimated 158 million books in the world. Before a library board commits to restricting access to books, one would necessarily ask why a tiny library like Eagle would have more than two dozen books that could be considered “harmful”? In other words, why are the books are being purchased in the first place? Does the law do anything to stop or even pump the brakes on that? Of course, the answer is no.

Even with the new law, objectionable books are still being purchased at taxpayer expense. If anything, the law frees — even authorizes — libraries to continue to make questionable book purchases. But I think it’s more concerning that the law now gives government library boards the obligation to create lists of “banned books” or “restricted books” which then draws attention to those books that might not ever amount to anything but not for having appeared on a government book list.

Giving a book the designation of “banned” or “restricted” by government is the ultimate attractant. It fuels interest rather than lessen it.

It’s easy to argue that the reason any of this is happening across the nation is because of leftism in academia which has trickled down into the librarian community, and that may play a role here. But it also boils down to the immutable law of government agencies and programs: they exist to remain relevant and to grow. Never forget that public libraries are government agencies.

Hoffman suggests that Eagle could take nearly $2 million spent on the library and instead buy e-readers for every man, woman, and child in the city. (He clarifies that he’s not advocating such an action, just pointing out an alternative.)

Hoffman concludes by saying that public libraries are not necessarily the proper function of government at any level:

It would benefit everyone if the government would be completely out of the book selection business, freeing people to decide on their own which books to view and which to avoid. It would also put an end to questions about what books the government is purchasing and why, and questions about what books belong on list and which don’t. That would be the best outcome for intellectual advancement in the 21st century.

I struggle with where to draw the line regarding the proper role of government. It’s easy at the federal level: read the Constitution. Much of what the federal government does today is outside of the enumerated powers our Founding Fathers gave it. States have more power — many of our Founders believed that states could do a lot that the national government could not do, such as establish a state church. Idaho’s constitution requires our state to maintain a public school system, for example.

Cities are a different animal. Residents often choose to live in cities partly because of the public amenities available. Cities maintain parks, youth sports leagues, public libraries, and many other services that most conservatives believe fall outside the scope of state or federal government. Cities also frequently take steps to attract not only residents but businesses, which contribute a significant portion of the taxes that fund these amenities.

Public libraries were one of the great ideas of Western civilization, and I believe they still have a role to play in the 21st century. The Eagle Public Library not only houses physical books but also offers digital and audiobooks, movies, board games, cake pans, audiovisual equipment, and even seeds for your spring garden. The Family Place Space provides a fun and safe environment for young children to play, while the desks and workrooms offer people of all ages a quiet place to work, do homework, or simply read a book. The library is one of the few civic institutions that serve people of all ages and demographics, and it is therefore a meeting place for the community.

Perhaps the old model of private organizations or wealthy benefactors creating public libraries would be more appealing to libertarian sensibilities than taxpayer-supported institutions, but in any case, libraries are here to stay. It’s up to you to ensure that your public library reflects the values of your community and fulfills its mission of providing information and entertainment for all ages.

If your local library isn’t properly fulfilling its mission, you must take action. Start by having a conversation with the library director to share your concerns and learn more about how things operate. Attend library board meetings, and use public comment time to voice your thoughts. In the two years I’ve served on the Eagle Library Board, I can count on one hand the number of people who have taken advantage of the right to public comment.

If your library is an independent taxing district, you can support challengers to incumbent trustees or run for a position yourself. If it’s part of a city, as in Eagle, you can still speak with the trustees but also share your concerns with the mayor and city council.

Our job as citizens of a republic is to manage public institutions for the good of the community, rather than allowing them to be taken over by career bureaucrats and leftist activists. It’s time for Christians and conservatives to stop abandoning these institutions and instead reclaim them. The library is part of our heritage as Americans, and it’s up to us to ensure it stays true to its mission.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.