If there’s one thing I hear conservatives and Republicans consistently complain about, it’s how the left marches in lockstep while the right fights among itself. While I think this is somewhat exaggerated — Democrats, too, often argue among themselves — there is truth to the idea that conservatives tend to waste time and energy on infighting rather than presenting a unified front.

Moderates and traditional conservatives are often tempted to disavow those to their right to curry favor with the left. News outlets and groups like Media Matters frequently find some controversial statement by a figure on the right, demanding that other conservatives and Republicans not only condemn the statement but also the individual behind it. If they refuse, these same outlets add them to the disavowal list.

On the farthest right, groups like paleoconservatives, libertarians, and others often condemn those they see as less conservative, labeling them “Republicans in Name Only” (RINOs), sellouts, or outright leftists. This can quickly lead to a “purity spiral,” where each faction cuts ties with those they deem insufficiently conservative, only to be shunned in turn by others to their right.

As usual, I manage to irritate both sides. In 2022, I defended Lt. Gov. Janice McGeachin’s decision to speak via video to AFPAC, the America First Political Action Conference. While the left-wing media and “respectable” conservatives condemned McGeachin, I argued it’s better to reach out to these young people rather than ostracize them, which only drives them to be more radical and edgy.

On the other hand, I have resisted attempts to exclude people from the conservative movement for not being far enough to the right. There are some who routinely decry everyone outside their small circle of activists as sellouts, making no distinction between conservatives who aren’t sufficiently libertarian, moderate or liberal Republicans in the Main Street Caucus, and even Democrats. Then they wonder why it’s so hard to rally support for their candidates and causes come election time. You can’t constantly attack people and then expect their support.

A few years ago, conservative writer and firebrand Charles Haywood coined the phrase “no enemies to the right” (NETTR). His point was that conservatives should present a united front against our real adversaries on the left rather than waste energy on internal conflicts. In a debate with Daniel Miller at IM-1776, Haywood explained:

If we begin with the end in mind, we see that any firepower directed at the Right is necessarily antithetical to the goal of destroying the Left. Any contentious discussion with those on the Right, wherever exactly they may fall on the spectrum of “not Left,” should instead be done privately and be strictly tactical, to agree on how may we cooperate to achieve our joint ends. We may occasionally choose to ignore some on the Right, as charlatans, simpletons, or fools, or simply too different, even malevolent, in their beliefs, but attacking them publicly only serves to make it harder to reach our end.

The phrase “no enemies to the Right” is merely the expression of this approach.

Others on the right disagree, whether they’re “respectable” conservatives wanting to distance themselves from what they view as toxic or controversial elements, or “far right” figures seeking to ostracize those they see as insufficiently conservative. Miller’s responses to Haywood in that debate are worth reading.

Haywood was speaking mainly about the temptation to disavow controversial extremists on what many consider to be the “far right,” but I suggest it applies equally in both directions, which is why I have tried to adopt this framework for my own discourse. Some other conservative commentators, including Idaho’s own Pastor Doug Wilson, have called this “No Enemies On the Right,” or NEOTR:

NEOTR assumes a large body of generally like-minded people, all of them opposed in various ways to the leftist revolution. And some of those people opposed to the revolution are undeniably on the right, while at the same time being on my left. In fact, a lot of them are.

If I have a disagreement with someone on the right, I would prefer to address it privately rather than engage in a public argument. Public infighting only serves to weaken our movement while providing mirth to leftists and their allies in the media. Make no mistake, when conservatives clash on social media, leftists are enjoying ever minute, bowl of popcorn in hand.

This doesn’t mean we avoid calling out nonsense or debating issues. Even Haywood, after all, engaged in a public debate with Miller over NETTR. Since starting this platform on Substack, I have responded publicly to Republican figures like Trent Clark, Laurie Lickley, Mary Souza, and Daniel Silver, sometimes in uncompromising terms. I try to focus on the issues, however, rather than attacking the individuals. Do I always succeed? Of course not, but that is my aim.

I was highly critical of the Gem State Conservatives leading up to the State Convention, but once it was over, I directed my rhetoric at the left, inviting all Republicans to work together to defeat Prop 1 and the Democrats. When the session begins and legislators start voting on bills, I’ll continue calling things as I see them, doing my best to debate the issues rather than going after individuals.

In this time of political realignment, it is imperative to build bridges to form winning coalitions. Yet, as my friend Dan McKnight once told me, those bridges must be built upon solid, principled foundations. I don’t agree with everything Donald Trump says or does, but I am glad to see him leading the MAGA movement. I don’t align with Robert Kennedy Jr.’s positions on guns or the environment, but I welcome his presence in the movement because of his focus on health and skepticism of Big Pharma.

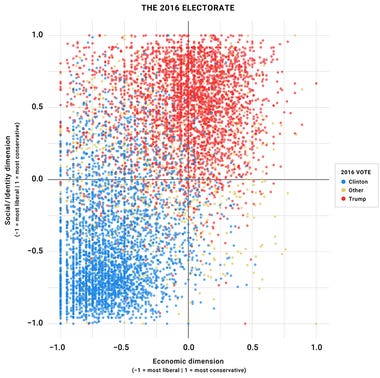

After the 2016 election, someone made a chart showing voter preferences for Trump, Hillary Clinton, and third parties based on a two-axis political compass. The x-axis represents economic views (libertarianism on the right, socialism on the left), while the y-axis shows social views (traditional values at the top, progressive values at the bottom). Trump’s electorate in 2016 was largely socially conservative yet economically centrist.

The bottom right corner of the graph — the emptiest area — is where the old guard Republicans such as Mitt Romney and John Kasich live. Notice there are few voters in that quadrant. The old neoconservative line that we want low taxes, free trade, and to completely ignore social issues is dead on arrival. With apologies to James Carville, it’s not just the economy, stupid.

That doesn’t mean we sacrifice principles, but as I’ve written many times, we must figure out how to apply those principles to a vastly different country than the one our grandfathers grew up in. That means, for example, building a coalition of people as diverse as J.D. Vance, Robert Kennedy Jr., and Tulsi Gabbard. It also means we can stop trying to please former Republicans like Romney, Kasich, Liz Cheney, or Adam Kinzinger.

The emerging Republican coalition is not quite so wedded to talk radio shibboleths about tax cuts and small government, and is much more willing to express skepticism of big business and civic institutions. In response to claims that this or that policy is not “conservative,” people within this coalition rightly point out that conservatives were unable to conserve even the women’s restroom, much less our culture, and it’s time to try something new. This is not your grandfather’s Republican Party.

What does this mean in relation to NETTR? It means that, to win public office and enact policies that reflect our principles, we need to build coalitions with a broad range of allies. This means debating issues, not demonizing individuals.

I see a tendency on all sides in Idaho’s political debate to cast people as heroes or villains. I keep saying that politics should be about policy, not personnel. Too often we fall into a cult of personality, both in how we worship our favorite figures as well as in how we demonize those we dislike. Once someone is in one box or another, it’s hard to change your mind. “You can’t trust this representative; he was endorsed by IACI.” “I won’t listen to that senator; she’s with IFF.” It’s the same story over and over. Leftists and moderate Republicans denounced Rep. Heather Scott for something as banal as taking a picture with a Confederate flag to show her commitment to free speech, while some conservatives have denounced her for supporting Speaker Mike Moyle in the recent primary.

If you spend all your time ostracizing or excommunicating anyone who disagrees with you on any single issue, you’ll soon find yourself with a constituency of one — a surefire way to lose every election. On the other hand, if you constantly disavow conservatives who say anything remotely controversial while cozying up to leftists, people will rightly begin to wonder whose side you’re really on.

No Enemies to the Right doesn’t mean we avoid disagreement or even forceful debate. It means we hash out our differences behind the scenes while uniting to face the real enemies when the battle begins. It means we focus on the issues, not the characters. It means we stop playing the role of tattletales, constantly looking for reasons to kick someone out of the club. It means we exercise discipline on social media, rather than putting on a show for the left.

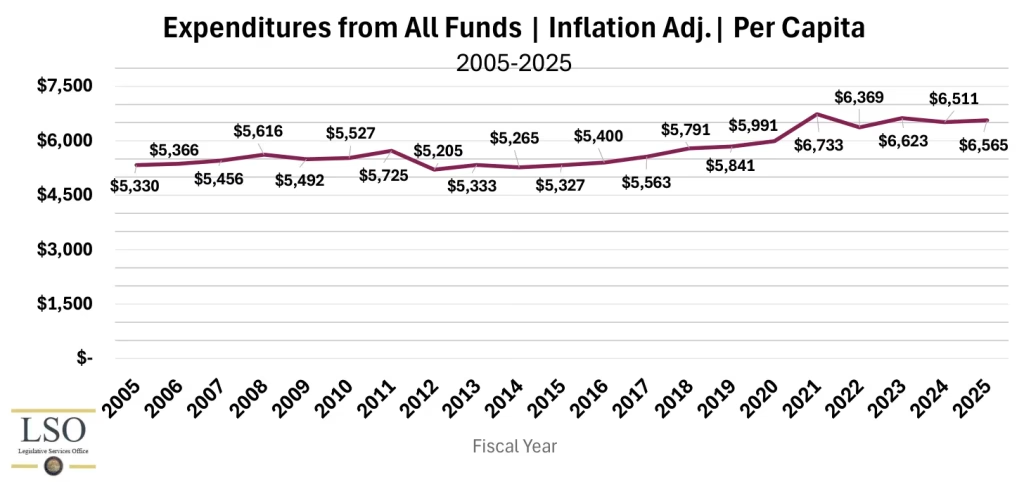

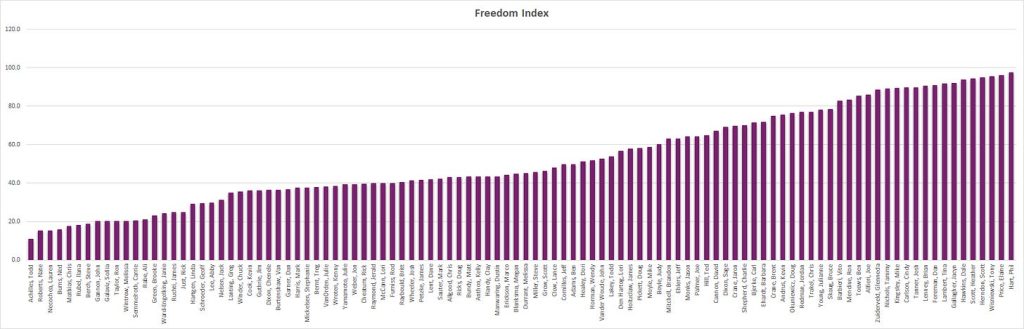

Above is a graph of legislators based on their 2024 Freedom Index scores. If you ask 20 random Republicans where to draw the lines between “extremists” and “reasonable conservatives” and “RINOs” you would get at least 40 different lines. Rather than using a microscope to figure out how to divide the movement, I think our time is better spent moving forward with a positive vision based on our timeless principles. Those who want to get on board are welcome, while those who oppose us are invited to get out of the way.

Paid subscribers head over to Substack for a spicy bonus note. Not subscribed? Sign up for free to get daily posts, or support my work!

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.