Just over a month ago, Christopher Rufo exposed how welfare fraud in Minnesota’s Somali community was not only being exfiltrated from the country, but was potentially funding terrorist networks such as Somalia’s Al-Shabaab:

In many cases, the fraud has allegedly been perpetrated by members of Minnesota’s sizeable Somali community. Federal counterterrorism sources confirm that millions of dollars in stolen funds have been sent back to Somalia, where they ultimately landed in the hands of the terror group Al-Shabaab. As one confidential source put it: “The largest funder of Al-Shabaab is the Minnesota taxpayer.”

Our investigation shows what happens when a tribal mindset meets a bleeding-heart bureaucracy, when imported clan loyalties collide with a political class too timid to offend, and when accusations of racism are cynically deployed to shield criminal behavior. The predictable result is graft, with taxpayers left to foot the bill.

The New York Times picked up the story a few weeks later, exposing left-wing readers for the first time to the rampant fraud in the Somali diaspora—something conservatives have been discussing for years:

The fraud scandal that rattled Minnesota was staggering in its scale and brazenness.

Federal prosecutors charged dozens of people with felonies, accusing them of stealing hundreds of millions of dollars from a government program meant to keep children fed during the Covid-19 pandemic.

At first, many in the state saw the case as a one-off abuse during a health emergency. But as new schemes targeting the state’s generous safety net programs came to light, state and federal officials began to grapple with a jarring reality.

Over the last five years, law enforcement officials say, fraud took root in pockets of Minnesota’s Somali diaspora as scores of individuals made small fortunes by setting up companies that billed state agencies for millions of dollars’ worth of social services that were never provided.

The day after Christmas, YouTuber Nick Shirley published a video showing how dozens of Somali-run daycare centers in Minnesota most likely exist only on paper, despite receiving tens of millions of dollars in taxpayer subsidies. The video went viral, with more than 121 million views on Twitter as I write this:

Twitter poster Aceofhearts followed up with a search of a random city—Boise—and found dozens, perhaps hundreds, of licensed daycare facilities with foreign-sounding names. Her tweet had more than 1.4 million views at this writing.

It made me wonder how much of this is going on in Idaho. There are multiple levels here—outright fraud, like what Nick Shirley found in Minneapolis, but also networks of people deliberately taking advantage of loopholes in systems designed to help the most vulnerable. Remember Jannus? The NGO operates a network of agencies that aim to divert as many tax dollars as possible into their system:

It is one small part of a massive web of NGOs and nonprofits, all designed to convince the government to take more of your money and give it to them for their own purposes. While the mythical Janus had two faces, the modern Jannus is akin to the hydra, which had many.

One head of this hydra issues reports like this, claiming that we need higher taxes to support more government spending on social programs. Another head lobbies the Legislature to create more of these social programs and to appropriate more money—federal and state—to them. Finally, yet another head stands ready to apply for these new grants and distribute them as they see fit. Oftentimes, the purpose of the grants is to incorporate more people into government dependence. Refugees, for example—the primary focus of Jannus now—are brought here and immediately enrolled in myriad taxpayer-supported programs, all with Jannus acting as the middleman.

One of the many heads of the Jannus hydra is a program called Economic Opportunity, which helps refugees start their own businesses through training and funding. A 2019 column in the Idaho Statesman lauded Jannus for this work:

They had help from Jannus Economic Opportunity, a Boise-based nonprofit, using a small federal grant. Jannus EO taught them business, accounting, and child-care regulations. It provided $1,300 apiece for licensing, insurance, books and startup equipment.

Today, Jannus-trained refugees operate a remarkable 64 licensed day care facilities, 10 percent of Boise’s total. Their market niche is caring for the children of people who work night shifts and the odd and broken hours that are left to refugees and poor people.

With tears in her eyes Jannus EO Director Kate Nelson says, “These women inspire my hope for humanity.”

One of the women profiled in the column was Zainab Dalib, who, along with her five children, came to Idaho as a refugee from Somalia in 2012. According to records from Transparent Idaho, Dalib was paid more than $350,000 in welfare from July 2019 through June 2023. (Many records on the site appear to stop in 2023.)

The 2019 column was not the first time Dalib was profiled. A CBS 2 article in 2017 explained how she took advantage of another Jannus program:

…she worked in the hospitality industry when she initially moved to Boise five years ago. She did that until she found out about the Refugee Childcare Business Development Project, under the Idaho Office for Refugees. The project helps refugees, mainly single mothers, start their own in-home day cares.

The article went on to explain how the system works:

Now, these caretakers will watch up to six children at a time, at their own homes or apartments. All the refugees who go through the program get licensed within the city of Boise, or the state, and they’re all signed up with ICCP: the Idaho Childcare Program. ICCP helps working, low-income Idaho families.

“Over 98 percent of the families who are enrolled in these child cares utilize ICCP program,” Nelson said. “And there is a shortage of ICCP providers, because it’s optional for a childcare provider to accept ICCP.”

Mainly, women are involved in the child care project, and most of the time they watch other refugee children.

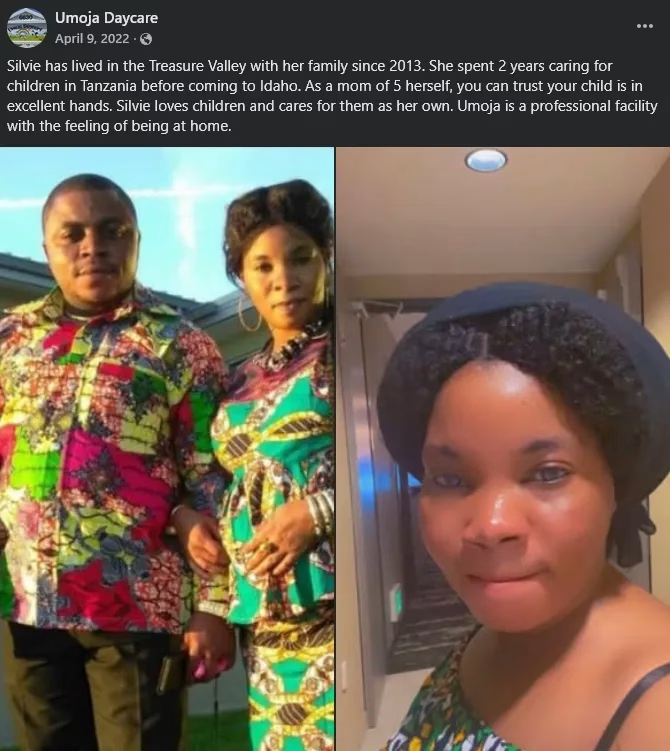

Last night, I posted a thread on Twitter about another refugee small business owner. Silvie Mwenematale, a mother of five, came to Idaho from Tanzania in 2013. In 2019, she opened Umoja Child Care on Overland Boulevard in south Boise.

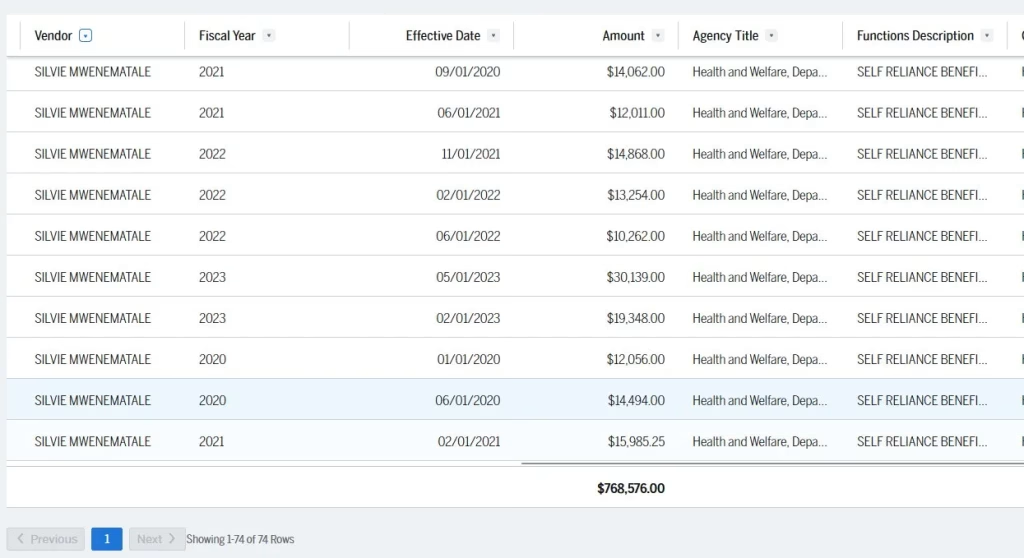

According to Transparent Idaho, Mwenematale received more than $750,000 in welfare from Idaho taxpayers between November 2019 and June 2023. Payments started around $12,000 per month in 2019 but ballooned to more than $30,000 per month by the time records ceased in 2023.

Mwenematale was twice charged in 2023 with misdemeanors for allowing an unlicensed person to supervise children at her daycare. That same summer, Umoja’s participation in the Idaho Child Care Program was terminated over concerns of noncompliance. However, the daycare’s Facebook page has apparently not been updated in quite some time, as it still states that Umoja accepts only ICCP payments.

Mwenematale failed to file an annual report for Umoja Child Care LLC in 2025, and the company was terminated in October of this year. A collections agency sued Mwenematale this summer for nonpayment of a $12,000 debt, receiving a default judgment earlier this month.

The address Mwenematale used in her initial 2022 filing for Umoja Child Care LLC is owned by Bellancine Mukeshimana, who is listed on Idaho Child Care Check as the proprietor of Bella Day Care in another home just around the corner. I drove through the neighborhood this morning and saw no evidence of a daycare. Bella Day Care does not appear to have an online presence, either.

I also drove by Umoja Daycare in Boise. It’s gone now, but a new business has appeared in its place: Yetu Sote Daycare.

Yetu Sote shares the grounds with another daycare called Piruetas, which, according to its website, is run by a couple from Venezuela. Yetu Sote Daycare LLC was created in April 2024 by Agnes Murekatete, and according to Idaho Child Care Check, it was inspected twice last April, passing both times. I chatted with someone who works nearby who confirmed that Umoja Daycare did have children coming and going while it was in operation, so at least that much was real.

There appears to be a distinction between completely fake daycares, like those Nick Shirley found in Minnesota, and those that serve a small number of children from the same insular community. The former is outright fraud; the latter is engineered to exploit the system. Some in the latter category may also engage in fraudulent practices involving the many subsidies available, but uncovering that would require a much deeper investigation.

The child-care industry was already heavily subsidized before the COVID-19 lockdowns threatened to upend it entirely. The American Rescue Plan of 2021 delivered $138.6 million to Idaho for the Child Care Stabilization program, covering wages, rent, and supplies. The federal government also increased investments through the Child Care and Development Fund. The Idaho Department of Health & Welfare expanded its own subsidies through the Idaho Child Care Program, leading to cost overruns in 2024:

The Idaho Legislature retains the authority to appropriate federal funds for the CCDBG program, but it is administered by the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare (IDHW) under the Idaho Child Care Program (ICCP). For fiscal year 2024, the Legislature appropriated just over $52 million for ICCP, which currently serves 7,800 children in Idaho.

ICCP is just one childcare subsidy available to Idaho families. The Workforce Development Council has limited grants for childcare and there is a state tax credit that can defray costs of up to $12,000 per eligible child.

Last week, IDHW Director Alex Adams informed the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee that ICCP is $15 million over budget this year and is expected to go $22 million over budget next year. Rather than asking for a supplemental budget, Adams said he would work with the department to correct the causes of overspending.

These subsidies, along with additional public and private grants available to immigrants and refugees, make child care a field that offers quick and easy money. None of this is proof of fraud, but it raises serious questions. Just two women—Silvie Mwenematale and Zainab Dalib—received more than $1 million, courtesy of taxpayers, over a four-year span. That is on top of whatever private donations and passed-through federal dollars they may have received. For example, Mwenematale was gifted $1,850 by a nonprofit called the Krazy Coupon Lady Foundation, which distributes cash grants to refugees in the Treasure Valley. The foundation was created in 2016 by Heather Wheeler and Joanie Demer, cofounders of the Krazy Coupon Lady.

Helping people feels good, and helping people who have fled war and violence surely feels even better. At what point do we put our feet down and say that American tax dollars—if they must be used for charitable purposes at all—should be reserved for American citizens?

There are also touchy questions about cultural clash. Some cultures view fraud not as immoral, but as a legitimate way of earning money. Consider Somalis in Minnesota sending ill-gotten gains back to their home country. They feel no shame at defrauding—or at least exploiting—these welfare programs; they believe themselves clever for funneling tax dollars to their own people, while the rest of us go to work and pay our taxes.

Did you know that, prior to this year, refugees with incomes up to 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines were eligible for medical assistance programs—higher than the 133 percent threshold for American citizens? Rep. John Vander Woude and Sen. Josh Keyser sponsored House Bill 199, which brought the refugee threshold into alignment at 133 percent. I was in the room as the Senate Health & Welfare Committee debated the bill. Refugees and their advocates testified against it, while Sen. Melissa Wintrow, the committee’s lone Democrat, argued that the bill was not very neighborly.

Watch the full debate here:

H199 passed both chambers on strict party-line votes.

Democrats frame these handouts for immigrants and refugees as compassion, while Republicans generally seek to prioritize citizens and ensure the law is followed. Yet there may be another reason Democrats are reluctant to scrutinize welfare programs too closely. How many tax dollars laundered through welfare schemes end up back in their hands via campaign contributions? It is well known that ActBlue, the Democrats’ payment processor, is likely a vehicle for fraud and money laundering. What better way to ensure the money continues to flow?

Indeed, online sleuths discovered that Somali daycare facilities in Minnesota were maxing out contributions to a Somali political candidate in Washington State. Ubax Gardheere ran for King County Council in 2021, winning the Democratic primary but losing support after voters learned of a 2010 incident in which she boarded a school bus, ranted about U.S./Somalia relations, and implied she might blow up the terrified middle-school children. She later dismissed the incident as a mental-health crisis.

This story touches on nearly every political debate, from immigration and refugees to government welfare and dependency. It’s blowing up on social media—my own post on Umoja Daycare has received more than 80,000 views over the past day. While that’s small potatoes compared to Nick Shirley’s 121 million, it demonstrates how frustrated the American people are with what’s going on.

This will surely remain a hot topic when the Legislature convenes in two weeks. Exposing actual fraud should be low-hanging fruit for Republicans, and trimming back exorbitant subsidies for noncitizens should also be an easy debate. One thing is certain: a system this generous, this opaque, and this lightly supervised is an open invitation for abuse. Idaho taxpayers deserve better.

Feature image from Umoja Daycare on Facebook.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.