Whether or not Jesus Christ was actually born on December 25 doesn’t really matter. King Charles III of the United Kingdom was born on November 14, but his British subjects typically celebrate his birthday on the third Saturday of June, since it offers much better weather for outdoor celebrations.

Nevertheless, I’ve heard some fairly convincing evidence that it might well have been on that date. It at least makes sense why early Christians would have believed it so. The idea that those sneaky Christians picked the date in an attempt to overshadow Roman festivals such as Sol Invictus is nonsense—evidence shows Christmas being celebrated on December 25 as early as AD 200, while the establishment of Sol Invictus didn’t occur until 274.

Constantine didn’t end the persecutions until 313 anyway, so it’s not like early Christians had any institutional power in the 3rd century.

As I said though, it really doesn’t matter. What matters is the why.

Christmas isn’t the highest holy day of the Christian calendar—that would be Easter. But it has nevertheless become the central American holiday, perhaps because it falls so close to the end of the year, serving as both a capstone to what was and an anticipation of what is to come. It has also turned out to be the most susceptible to commercialization.

While some Christian denominations tried to ban Christmas throughout the centuries—whether because they believed it was frivolous, idolatrous, or something else—American Christians embraced the holiday. In 1823, an upstate New York newspaper published “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” helping define the American concept of Santa Claus. In the two decades surrounding the Civil War, Americans composed carols such as “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear,” “We Three Kings,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” and “Jingle Bells.”

The early to mid-20th century solidified traditional American Christmastime. From paintings by Norman Rockwell to advertisements by Montgomery Ward, imagery of trees, bells, wintertime, and Santa Claus became indelible in the minds of the American people. Songs composed in this period were less about the Christmas story itself than about the traditions that had grown up around celebrating it—“Santa Claus Is Coming to Town,” “Winter Wonderland,” “White Christmas,” “The Christmas Song,” “Sleigh Ride,” and so many more.

Many songwriters of this period were Jewish, seeking to assimilate into the American Christmas tradition.

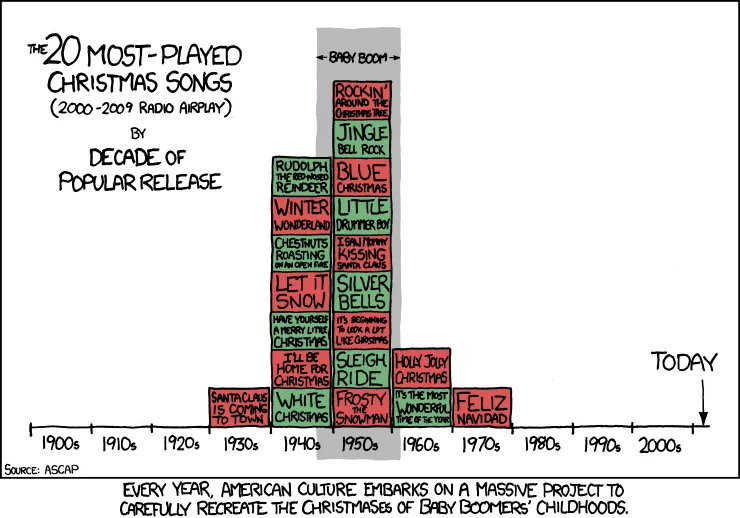

An xkcd comic from about ten years ago demonstrated how the most popular Christmas songs of the 2000s reflected Baby Boomer childhood nostalgia.

It’s probably changed in the last 10–15 years, in any case. Culture is always evolving, though the rise of streaming services like Spotify has had the effect of freezing that evolution, allowing people instead to live eternally in a time of their own choosing.

Yet the story of Christmas is eternal. We tend to celebrate it through a 20th century American lens, but we should never mistake the celebration for the event itself. God entered the world in incarnate human form, a helpless baby, honored by shepherds and wise men, pursued by kings. He came to die, and died to save mankind. If it ended there, it would be an epic story, an inspiring tradition, a piece of our culture. But it didn’t end there. Christ rose again, conquering death and the grave, and offering salvation and eternal life.

Christianity began with a handful of frightened disciples, and within a few centuries was the dominant force in the Western world. Today it is fragmented, with followers fighting amongst themselves, unsure of our identity as we begin the second quarter of the 21st century. Yet no matter what turns of history, no matter how it has been implemented by leaders and cultures throughout history, Christianity remains, as C.S. Lewis put it, the myth that is true.

Americans don’t have a monopoly on the truth, nor on Christianity. Yet it is nevertheless the lens through which we view that truth. We can’t expect anything else. This is our culture, our heritage, our worldview. Our minds have been shaped by centuries of history, and we can no more step outside that than fish can step outside water.

“Sleigh Ride” might be my favorite secular Christmas song. It’s not even really a Christmas song—the only celebration mentioned in the lyrics is a birthday party at Farmer Gray’s home—but that’s part of its charm. It’s all about the imagery: taking a ride on a cold winter’s day, gathering with family and friends around a hot fire, enjoying company and fellowship. It’s the sort of celebration we can easily imagine taking place at Christmastime.

It’s a reminder that all of this—the songs, the gifts, the trees, bells, and holly, the fellowship with family and friends—is the penumbra of something deeper, something important. That doesn’t make those things meaningless; rather, it makes them more meaningful when they point toward the Truth. Jesus really is the reason for the season.

I wish you all a very happy Christmastime with family and friends. Enjoy the celebrations, but remember why we celebrate. May God bless you all!

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.