It’s a given that nobody likes taxes. While many citizens enjoy some of the things taxes pay for—roads, public schools, libraries, law enforcement, fire protection—few have positive feelings about the taxes themselves.

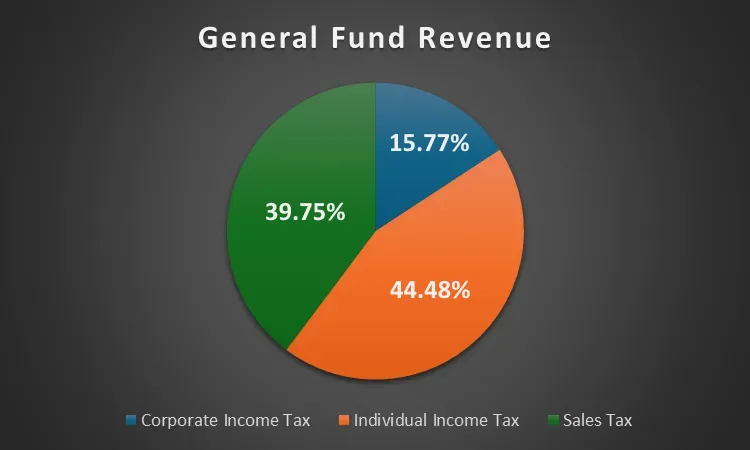

Idaho’s governmental revenue structure rests on a three-legged stool of income taxes, sales taxes, and property taxes. Based on projections for fiscal year 2025, income taxes—levied on both corporations and individuals—make up about 60% of General Fund revenues, while sales taxes account for just under 40%.

Property taxes, of course, are levied by counties, cities, and special taxing districts.

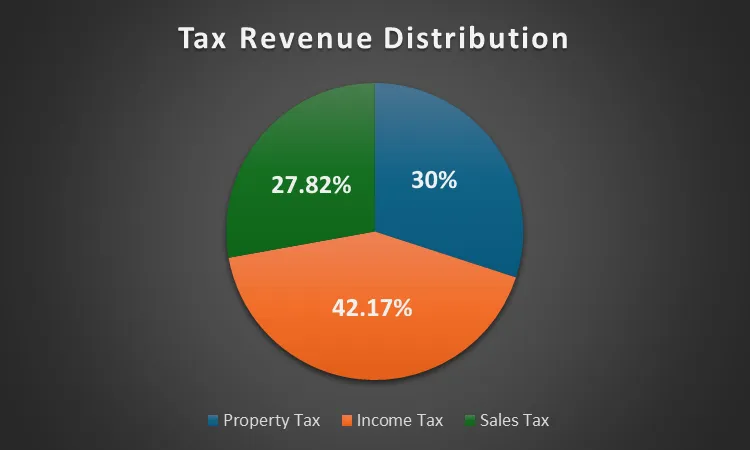

Using ChatGPT to estimate FY 2025 property tax payments based on past years and projected growth gave me a number of about $2.3 billion. Though just a rough estimate, it works for our purposes here in examining the three-legged stool. Using those numbers gives us the following distribution of taxes paid to Idaho governments:

Keep in mind that not all of these taxes are paid by Idaho citizens. Travelers and truckers pay gas taxes as well as sales taxes on purchases, while out-of-state landowners pay property taxes.

Assuming, for the sake of argument, that there must be some form of taxation to fund essential and constitutional government services, what is the ideal? Proponents of the three-legged stool suggest that keeping all three legs maintains a certain balance, allowing each to be kept lower than it would be otherwise. They warn that removing one leg—say, by abolishing property taxes—would force the other two to rise to make up the difference.

On the other hand, some argue that one or more of these taxes should be eliminated altogether. Citing the immorality, inefficiency, or regressiveness of a particular tax, they propose funding the state entirely through just one or two remaining sources.

If you really want an in-depth look at the relationship between Idaho’s various forms of taxation—and how we compare to other states—check out the Tax Commission’s most recent Comparative Tax Potential report. Feel free to review the full report for yourself, but to sum up: the data confirms that Idaho remains among the lowest states in the nation in terms of overall tax burden.

I’ve written a lot about taxes over the past year. Take the time to catch up with these articles if you haven’t read them already:

- Point/Counterpoint by Bryan Smith: Idaho’s Grocery Tax Must Go

- Point/Counterpoint by Carlos Vidales: Sales Taxes Are Fair Taxes

- The Truth About Property Taxes

- The End of Property Taxes?

- Are Taxes Immoral?

- Cut Spending by Cutting Taxes

- Idahoans Vote for More Property Taxes

- Can We Eliminate Property Taxes in Idaho?

As you can see, my personal focus has been property taxes, though I’ve tried to learn as much as I can about the entire system. I was just talking with someone the other day who pointed out that if we were to eliminate property taxes, we’d receive nothing from out-of-state landowners. It’s just another twisted thread in this tangled tapestry.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how many property taxes, though levied at the local level, are necessary to fulfill legislative mandates:

As you can see, while the Legislature doesn’t levy property taxes directly, it does pass laws that require counties and other districts to perform—and pay for—specific functions. Bringing property taxes under control will require more than attending budget hearings; it means working with your legislators to ensure that these mandates reflect the priorities and values of Idaho citizens as well as the proper role and scope of local government.

Prior to that, I explored the relationship between property taxes and government services. In that article, I quoted Margaret Carmel of BoiseDev, who explained how the state distributes sales tax revenue:

It might seem counterintuitive, but just because you buy something in Boise doesn’t mean your sales tax money heads right over to city hall to be spent.

Sales tax revenue in Idaho is collected throughout the state before heading to the Idaho State Tax Commission. From there, all of the tax money is redistributed to localities statewide based on a formula set by state law. This means localities all get a share of the total equal to a per capita rate, not the amount of money spent within their borders.

That throws another wrinkle into the equation, doesn’t it? Property taxes are levied by counties, cities, school districts, and other districts—often to fulfill state mandates—while sales taxes, levied by the state, are shared with cities and counties. In the article about government as a service, I pointed out that property taxes only make up a portion of a city or county’s total budget.

For Fiscal Year 2025, Ada County’s total budget was just under $391 million. About half of that—$172 million—came from county property taxes. Another $111 million (28%) came from department revenues, including payments from cities that contract with the county for police services, as well as fees from DMV transactions, trash collection, jail contracts, and more. Another $62 million (16%) came from the state and other governments—mostly from shared sales tax revenue, but also including liquor taxes, cigarette taxes, and reimbursements from the state judiciary. The remaining $46 million (12%) came from prior-year savings.

Bringing clarity and accountability to this system requires sustained effort from citizens and legislators alike to align spending mandates with both constitutional principles and common sense. No matter what, you need to be engaged and involved. Simply railing against taxes on social media won’t accomplish anything.

Eliminating property taxes is a popular idea—one I’m quite sympathetic to—but keep in mind that these are the most local of taxes. If we shifted responsibility for funding cities, counties, and special districts entirely to the state’s general fund, what would happen to local accountability?

Could a local sales tax option fill that gap? On my recent road trip to Arizona, I encountered varying sales tax rates depending on where I was. Receipts showed one line for state sales tax, another for the county levy, and yet another for a city tax. The downside of that system is confusion—how do you plan for sales taxes when every city and county sets different rates? I’ve really appreciated the consistency of living in Idaho, where the sales tax is 6% no matter where you go.

Of course, exempting groceries from sales tax remains a popular idea as well. But it’s more complicated than simply removing the tax on one category of goods, because doing so would affect revenue sharing. Every bill to repeal the grocery tax has included changes to the sales tax revenue-sharing formula, including Rep. David Leavitt’s personal bill filed last session. Go ahead and read the bill text to gain a greater appreciation for the complexity of the current system.

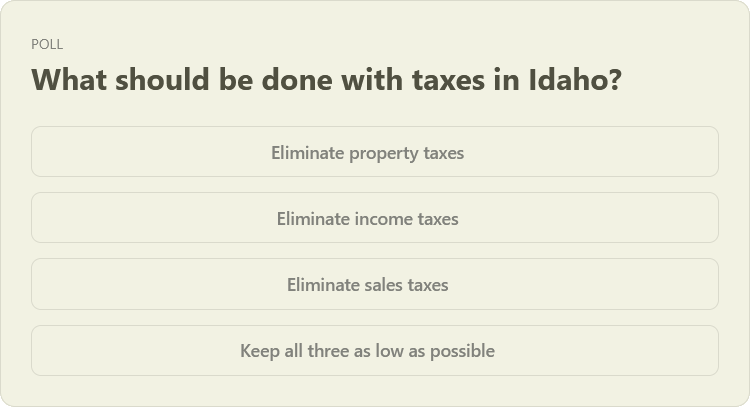

Taxation is a complex web of overlapping responsibilities and funding sources. Changing or eliminating one tax will inevitably cause ripple effects through the others. All that said, let me know what you think should be done with our three-legged stool. Subscribe for free over at Substack and cast your vote in the poll:

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.