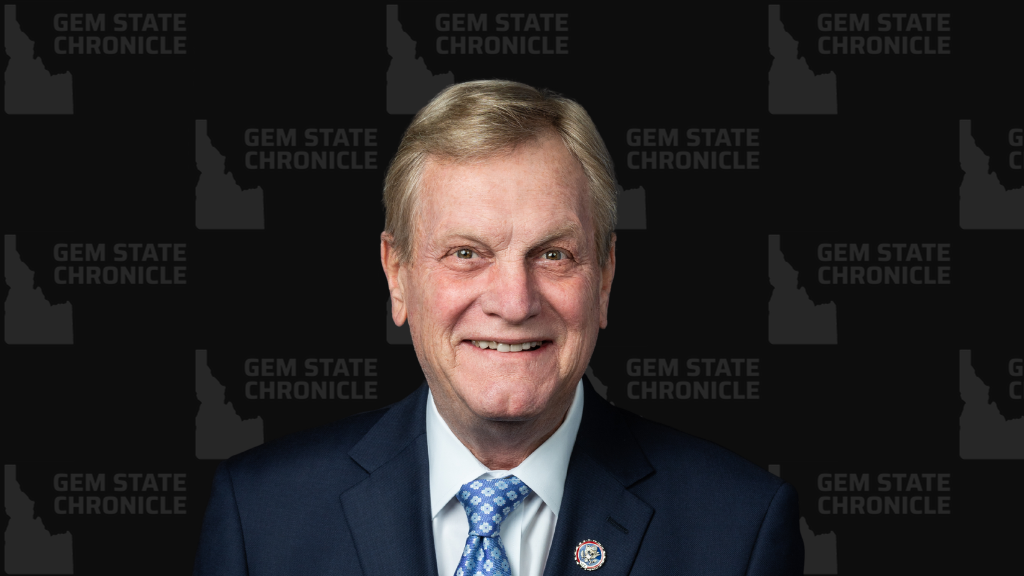

By Eric Parker | Originally published on the Mostly Peaceful Substack

ALL THE CHUCKLES ASIDE LET’S HIT A FEW POINTS WHILE IT’S HOT.

If you’ve spent any time on X lately, you’ve seen it—folks on both sides of the aisle raging about Senator Mike Lee’s proposal to sell off millions of acres of what they call “federal land.”

Senator Mike Lee says he only wants to sell 0.5–0.75% of federal lands. But 250 million acres are technically eligible. And once sold, they’re gone. The rancher loses his lease. The elk lose their range. The hiker loses her trail. The miner loses his claim. You don’t get it back. Public lands aren’t perfect. The feds have mismanaged them. But selling them to cover a budget shortfall is the equivalent of eating your seed corn. It’s shortsighted, it’s dangerous, and it hands control over to the highest bidder—often a global one.

I don’t want a federal monopoly. I don’t want a corporate one either.

I want what Idaho wants—what 82% of us said in a recent poll: Keep public land public. But manage it right. Manage it here. It doesn’t require a court battle. It doesn’t require a constitutional amendment. It just requires political will.

I’ve watched in real-time as people I respect get pulled into the same tired argument that’s cost us every court case for the last 40 years: “The federal government can’t own land.”

Let me be really blunt: That’s not the winning argument.

I’ve been in the courtroom. I’ve seen the government’s playbook. If we want to win—really win—we’ve got to stop swinging haymakers and start using strategy. That’s exactly what I’ve proposed in the Idaho Public Lands Management and Protection Act (IPLMPA).

Federal Land Ownership: The Wrong Hill to Die On

A lot of folks think the feds can’t own land because the Constitution never gave them the authority. I get it. It’s rooted in the Property Clause and Enclave Clause, and on the surface, it makes sense. Hell, I even believed it for a while until I first heard Dr. Angus McIntosh. But here’s the problem: every federal judge sees that argument coming a mile away—and they throw it out every single time. That’s exactly what happened to Utah in Utah v. United States, where they tried to reclaim millions of acres from federal management and got shut down 8–0 by the Supreme Court.

Let’s walk through those clauses for anyone who hasn’t done the deep dive:

The Enclave Clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 17) allows Congress to exercise exclusive jurisdiction over land “purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State” for specific uses like forts, arsenals, or dockyards. That’s not most BLM land.

The Property Clause (Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2) gives Congress the authority to “dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.” That clause has been interpreted by courts as granting sweeping authority to retain and regulate federal land, even permanently. But that interpretation was based on the assumption that the federal government can act like a landlord—without relinquishing full sovereignty.

But here’s what Dr. Angus McIntosh—one of the best minds I’ve ever studied under—taught us: The land may be federally titled, but the sovereignty remains with the states unless it was formally ceded under the Enclave Clause with state legislative consent. And guess what? That cession process rarely happened. That means state law still applies unless Congress proves it has exclusive jurisdiction.

McIntosh’s Core Legal Principle:

Even if the federal government holds title, it never acquired sovereign jurisdiction over those lands—residual state authority remains, except where land was acquired through the Enclave Clause. This is the “constitutional judo” underpinning our Idaho strategy.

Some claim that the Constitution’s Enclave Clause only allows the federal government to own land for forts, dockyards, or needful buildings “with the Consent of the Legislature of the State,” to them everything else is unconstitutional. That argument has failed in court over and over again. And it’s why Utah lost its recent federal land claim lawsuit at the Supreme Court. They challenged the federal government’s ownership.

The Enclave Clause governs exclusive federal jurisdiction—but not all federal ownership. The Property Clause (Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2) gives Congress the power to “dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.” This clause has been upheld repeatedly—from Kleppe v. New Mexico (1976) to Light v. United States (1911)—to confirm Congress’s authority over federal lands.

That’s why Utah lost. They claimed the government couldn’t own land at all. But the courts—going back over 100 years—have made it clear: the federal government can own land. The right question isn’t whether it can, but whether it should—and how that land should be managed.

Strategy, Incorporating Their Own Language

Here’s where the Idaho Public Lands Management and Protection Act comes in. Instead of challenging federal ownership head-on (and losing again), we pivot. We use their own statutes—their own language—as the foundation for our state law.

We pulled key principles from:

The Organic Act of 1897, which governs national forests and emphasizes timber and watershed protection.

The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, which regulates grazing on public lands and ties usage rights to base properties.

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976, which mandates that public lands be managed for multiple use and sustained yield—not closed off or sold for housing developments.

Why does this matter?

Because when we pass a state law that mirrors those federal principles, we don’t challenge federal law—we clarify and assert our jurisdiction alongside it. That’s constitutional judo. It’s not defiance—it’s incorporation. And when it lands in a federal courtroom, it’s hard for the DOJ to explain why a state using the exact language of Congressional statutes is somehow “in conflict” with federal authority.

Put plainly this tactic makes it legally and politically harder to strike down our law. It forces federal agencies and courts to wrestle with their own precedents—and it gives sheriffs, counties, and the Idaho Legislature a real lever to use.

A Foundation to Build On

The IPLMPA isn’t meant to be the final word. It’s the first step. It’s a framework—a foundation for Idahoans to build on through their own representatives.

If there’s a road closure that cuts off a rancher’s allotment—we fix it through the Act. If a prescribed burn damages grazing rights—we hold the agency accountable through the Act. If a mining claim is blocked or ignored—we protect that property interest through the Act. This isn’t about restoring some mythical “original” Constitution. It’s about giving Idaho the tools to fight back—legally, strategically, and effectively.

Here’s what the IPLMPA would do:

Codify Multiple-Use: Grazing, logging, recreation, mining, and habitat—balanced by Idaho’s own definitions.

Protect Grazing Rights: Enshrining the tie between base properties and allotments as real, defensible property interests.

Mandate County Coordination: No road closed or prescribed burn lit without consultation and consent of the sheriff and county commissioners.

Enforce Local Law Enforcement Jurisdiction: Federal agents cannot act unilaterally in Idaho counties without notifying and coordinating with local sheriffs.

Penalize Violations: Federal or state actors who violate these requirements could face fines or jail time.

This isn’t nullification. It’s not fantasy. It’s legal, it’s local, and it’s enforceable. It’s constitutional judo: using their own statutes, doctrines, and mandates to reassert our role in managing the land we depend on. Let’s be honest: the feds are overreaching. They closed roads without local input. They sold off allotments. They labeled law-abiding Americans as “domestic terrorists” for daring to protest. And now they want to liquidate millions of acres of land that supports our ranchers, hunters, and rural economies. Utah took a shot—and got flattened by the Supreme Court. Why? Because they used a blunt instrument and swung for the fence.

We’re not swinging. We’re leveraging. I don’t argue the feds can’t own land. I argue they don’t own it the way a sovereign landlord does. They hold it in trust, bound by constitutional limits, and subject to state jurisdiction unless exclusive jurisdiction has been properly ceded by the state. That distinction is crucial—and it’s why the real power to influence land use lies with us, not with a Supreme Court ruling. Idaho should be the tip of the spear in ending this decades-long battle. We’ve got the culture. We’ve got the case law. We’ve got the political will. Now we need the strategy.

The Idaho Public Lands Management and Protection Act isn’t just legislation—it’s a declaration that Idaho will no longer be dictated to by agencies that don’t understand our land, our way of life, or our Constitution.

Assert our jurisdiction, using their own language, under our own law.

That’s the win we can build off of and how Idaho can lead the way on putting this to bed.

About Eric Parker

Eric Parker is a husband, father, and working-class Idahoan who supports the 2nd Amendment, conservation, and criminal justice reform. He was acquitted after two federal trials and nineteen months in custody, and today fights against the weaponization of government. He currently serves as the state committeeman for the Blaine County GOP.