Yesterday afternoon, Mayor Robert Simison of Meridian delivered his 2025 State of the City Address. Perhaps the most consequential proposal he made was to place a permanent $5 million levy on the November ballot to fund law enforcement and first responders.

In 2023, Meridian accepted a federal grant that funded 18 firefighter positions, but that grant is set to expire next year. Simison’s proposed levy would fund those positions permanently and provide additional resources for the police department. It would also allow Meridian to establish its own prosecution office, ending its reliance on Boise for those legal services.

In debates about the proper role of government, most people agree that public safety is essential. However, since money is fungible, city councils can prioritize nonessential spending and later tell voters that unless taxes are raised, core services will be cut.

The federal government often plays the same game; holding popular programs hostage to secure unrelated spending. I recall one instance when a Republican-controlled Congress shut down the government during a budget dispute, and President Obama responded by closing national parks and even placing cones to block roadside views of Mt. Rushmore.

Still, voters expect certain services from their local governments. Asking citizens to approve a tax increase for clearly defined public safety functions might be the most transparent and equitable approach. Meridian voters will soon decide whether they’re willing to pay an additional $100 or so per year for more police and fire protection.

This got me thinking about how government increasingly resembles the subscription model that has taken hold across much of the private sector. Rather than buying a movie, we subscribe to Netflix. Rather than buying software outright, we pay monthly license fees.

Jared Henderson recently published an informative video on this phenomenon.

My 2024 property tax bill came to just over $1,600, or just over $130 per month. In exchange, I receive fire and police protection, access to well-maintained parks and trails, and support for public schools and community colleges. Even though nobody in my family attends public schools, they are ideally designed to produce a well educated citizenry that benefits the whole community. We can debate the efficiency or necessity of these services, but this is how the system is designed to function.

Of course, the key difference between private subscriptions and taxes is consent. Nobody forces you to subscribe to Netflix, but if your city council votes to raise taxes, you’re obligated to pay, even if you oppose it.

Some libertarians envision a fully voluntary model: you pay for the park when you use it, fire protection is an insurance policy, and police functions are handled by private security. Could that work? I’m not sure.

If you’re running one of the PACs that will likely campaign in favor of the levy—say, a firefighter or police association—you might ask voters, “Would you subscribe to a service that guarantees quick, professional help during an emergency for just $8 a month? Of course you would!”

Opponents, however, could argue that $100 per year is too much, especially when, as Mayor Simison noted, Meridian is already among the safest cities in the country. They may also point out that it’s misleading to claim the levy is only for public safety when the city continues to spend on less essential services. And once this levy passes, it’s permanent—no take-backs.

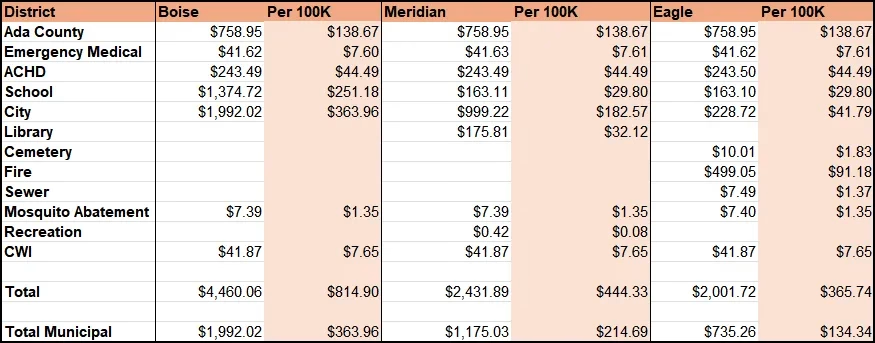

So what do taxpayers get for their involuntary subscriptions? For fun, I selected three homes—one each in Boise, Meridian, and Eagle—of similar size and valuation. I then normalized their tax bills using the amount each homeowner pays to Ada County to allow for a better apples-to-apples comparison.

To make the comparison even fairer, I also created a “Total Municipal Tax” row that combines city, fire, library, and sewer charges. Boise, for instance, operates its own fire and library systems. Meridian has its own fire department, but the library is part of a separate taxing district. Eagle has a separate fire district, but operates a city library.

As the numbers show, Boise levies $364 per $100,000 of home value for municipal services—far more than Meridian’s $215 or Eagle’s $134. Despite differences in population (Boise has 235,000 residents, Meridian has 135,000, and Eagle only 32,000), is there a logical reason why taxes increase so dramatically? Obviously more people demand more services, but does that necessarily follow that each taxpayer must pay even more? I suppose “climate justice” and whatever else Mayor Lauren McLean is championing don’t pay for themselves.

Property taxes, however, are just one part of the picture. In fiscal year 2024, Eagle’s total city revenues were about $52 million, but only $4.8 million came from property taxes. That’s under 10% of the total. Even when considering just the general fund ($32.5 million), property taxes still make up less than 15%.

Even if Eagle maxed out its legally allowed 3% property tax increase, it would generate less than $150,000—barely enough to hire one new skilled employee, and certainly not enough for major capital projects like renovating Heritage Park or building the new athletic complex along Highway 16.

In Meridian, by contrast, property taxes made up around 55% of general fund revenue in fiscal year 2025.

So if property taxes don’t fully fund city government, where does the rest of the money come from? One big chunk is sales tax revenue sharing, where the state redistributes tax money to cities. Margaret Carmel, writing for BoiseDev in 2022, explained how sales tax revenue sharing works in Idaho:

It might seem counterintuitive, but just because you buy something in Boise doesn’t mean your sales tax money heads right over to city hall to be spent.

Sales tax revenue in Idaho is collected throughout the state before heading to the Idaho State Tax Commission. From there, all of the tax money is redistributed to localities statewide based on a formula set by state law. This means localities all get a share of the total equal to a per capita rate, not the amount of money spent within their borders.

Prior to 2020, the distribution formula was based on property values throughout the state, which meant that expensive locales such as Sun Valley received a lot of sales tax revenue compared to other cities. Rep. Jason Monks sponsored House Bill 408 that year which changed the system to be mostly based on population instead.

Several Boise legislators voted against the bill, while city officials worried about the potential loss of revenue. Carmel quoted Boise’s then-budget director Eric Bilimoria who said:

From the City of Boise’s perspective, we are an economic engine for the state… Lots of activity has thrived here and our daytime population is higher than our nighttime population, so we need to provide additional police services and a whole slate of services for people within the city throughout the course of the day. None of that was accounted for.

So how are cities funded? Typically through:

- Local property taxes (with strict caps)

- Sales tax revenue sharing (based on population)

- Impact fees (levied on new development)

- User fees (permits, sports leagues, etc.)

Of these, impact fees tend to be the least controversial. “Growth should pay for growth” is a favorite phrase for politicians of all stripes. These are one-time charges on new homes and commercial buildings meant to cover the cost of additional infrastructure, including roads, parks, fire, and police. Developers pay the fees upfront, but pass the cost to homebuyers. So while impact fees spare existing taxpayers, they increase the cost of new housing, which is something many complain about as well.

State law strictly regulates these fees. For example, school districts are not allowed to charge impact fees, meaning any new schools must be funded by voter-approved bonds or state funds. Impact fees must also be public and transparent. Here are Eagle’s fees, which include parks, pathways, police, and fire. The city of Star, one of the smaller communities in Ada County, charges about three times as much in impact fees than Eagle. Eagle charges $111 in impact fees per new home for police, while Star charges over $3,300.

Shifting more of a city’s budget onto impact fees can please current residents who already complain about property taxes, but what happens once the explosive growth we’ve faced in the Treasure Valley for the last decade slows? Where will cities find the money to cover the inevitable holes in their budgets?

Back in 2022, the city of Nampa spun off its fire department into an independent taxing district after finding itself unable to keep up with its costs. What will happen to cities with low taxes like Eagle and Star, that rely heavily on impact fees to cover essential services?

Ultimately, the question comes down to how much residents are willing to pay for the amenities they expect from their cities. The upcoming levy will be an interesting test case; a referendum by Meridian voters on their council and the value they believe they’re getting from city government. Like it or not, we usually get the government we vote for.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.