There is a lot of land in Idaho. The Gem State boasts mountains, forests, deserts, lakes, rivers, and prairies full of sagebrush, all of which have drawn outdoorsmen to our beautiful state for many years. Prior to the American Revolution, the 83,570 square miles that we call Idaho today was the domain of hunter-gatherer tribes since before recorded history. Explorers and trappers, including Lewis and Clark, traveled through our mountains and prairies, bringing civilization and politics with them.

Anyone could see the vast wealth of natural resources our state had to offer, from gold and precious metals beneath the earth to thousands of acres of forests that could supply lumber for a growing nation, and vast grasslands capable of supporting large cattle herds.

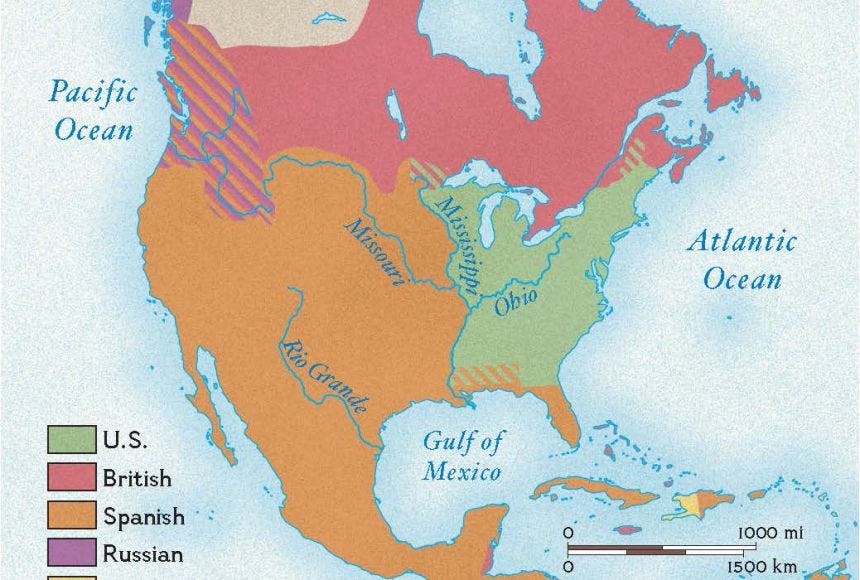

Soon these lands became the subject of a dispute between Great Britain and the young United States of America, which was formally resolved in 1846, and in 1863 President Abraham Lincoln signed an act creating the Idaho Territory.

On November 5, 1889, the citizens of Idaho ratified a new constitution and the following year President Benjamin Harrison signed an act admitting Idaho as the 43rd state of the union.

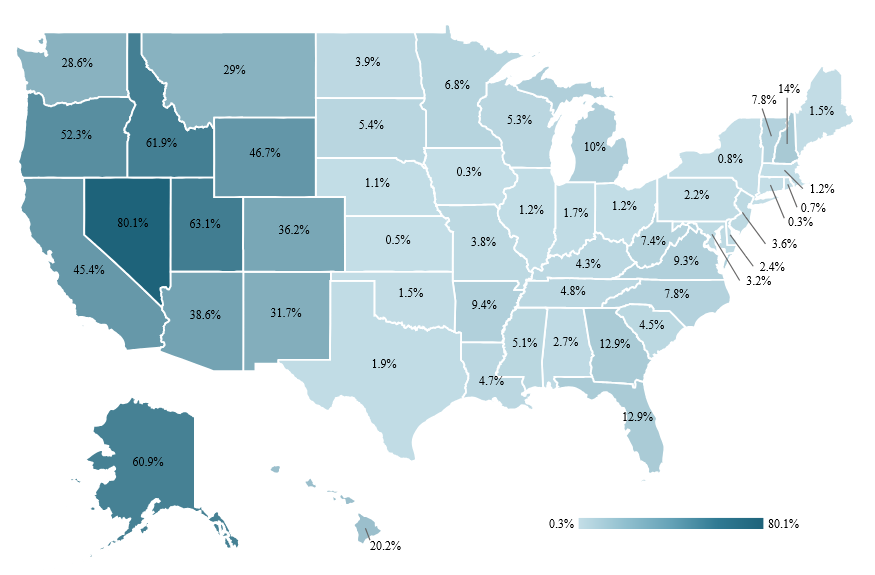

Yet the federal government held on to much of the land in the new state. Estimates today say that between 50% and more than 60% of our state’s land is managed by the federal government. This is the norm for states west of the Rocky Mountains, as you can see by this map from wisevoter.com:

The question of whether or not it is constitutional for the federal government to own (or claim, or manage, or whatever you want to call it) land within sovereign states is hotly debated. Proponents of states reclaiming land from the federal grasp point to Article IV, Section 3, Paragraph 2 of the US Constitution which says:

The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

On the other hand, as this pro-federal control article from the Grand Canyon Trust explains, “dispose of” does not mean the Constitution forbids the government from holding land, rather it gives Congress flexibility to decide what to do with it. According to the author, when the seven original states that had indefinite western boundaries ceded their land to the national government, it meant Congress could decide what to do with all the land from the Appalachians to the Pacific Ocean:

All states agreed to give that government the responsibility to determine the future of these lands, including overseeing their settlement and admitting new states as settlement advanced.

Ever since then, whenever the U.S. took control of lands from foreign governments and Native American tribes, Congress has exercised its “power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States,” the language of the so-called Property Clause of the Constitution adopted in 1787.

Nevertheless, this does not answer questions about what should be done going forward.

There are several offices within the federal government that manage public land. The Department of the Interior was created in 1849 to manage the natural resources of the growing nation following the Mexican War. 75% of federal land is managed by this department through divisions such as the National Park Service (NPS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), with most of the remainder managed by the US Forest Service (USFS), a division of the Department of Agriculture.

In 1864, President Lincoln signed an act giving the Yosemite Valley to California, with the stipulation that it could not be sold to private parties, and that it must be managed for the purposes of public use, resort, and recreation. Yosemite would be officially named a National Park in 1890.

Before that, however, Yellowstone National Park was set aside in 1872 as our nation’s first National Park. Since Wyoming was still a territory, the federal government managed it directly. In 1916, with ten National Parks had been established, President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Park Service Organic Act into law. The Act charged the new National Park Service with a mandate to:

…conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

Today, the NPS consists of 63 National Parks, 84 National Monuments, and dozens of other areas and sites that have been set aside for preservation. The NPS managed 84 million acres of land, nearly 3.5% of the total land area of our country. Another 8.5% is managed by the USFS, and 10.9% by the BLM. That means nearly one quarter of the land in America is managed by these three federal agencies, and large majority of that is west of the Rocky Mountains.

While the BLM was created in 1949, its predecessor agency the General Land Office (GLO) had been in existence since 1812. The GLO surveyed and administered public lands in the west, and usually handled the creation of titles to various tracts of land through the Preemption Act and the Homestead Act.

The GLO was placed under the new Department of the Interior in 1849. In 1891, President Grover Cleveland reserved 17 forested areas, initially placing them under management of the GLO. In 1905, Congress created the US Forest Service and moved management of the National Forests to that agency.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, ranchers and miners often utilized public lands for their own benefit. In 1910, Congress passed the Pickett Act, which authorized the president to temporarily withdraw these lands from private use. “Temporarily” eventually became “permanently”, and over the course of the 20th century a lot of land was withdrawn from private access.

In 1934, the Taylor Grazing Act created the United States Grazing Service (USGS) to manage rangelands and prevent overuse. In 1946, the GLO and USGS were merged into the new Bureau of Land Management.

All of this is to say that federal oversight of American land has been going on for a very long time.

The so-called Sagebrush Rebellion pushed back on national control of public lands. In 1976, Congress passed the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), which collated and superseded many of the acts of the previous century and a half. The Act ended the system of homesteading and gave the BLM more oversight over how federal lands were used.

Ranchers such as Wayne Hage and Cliven Bundy maintained that their families’ grazing rights predated both the federal agencies who now sought to regulate them as well as the statehood of Nevada and Idaho. This led to an armed standoff in the latter case. Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah attempted to introduce bills in the late 1970s and early 1980s that would allow states to begin taking back portions of federal land, but they did not pass.

Last month, the state of Utah filed suit asking the Supreme Court to rule on whether or not the federal government has the authority to indefinitely hold unappropriated lands within a state. Gov. Spencer Cox said:

It is not a secret that we live in the most beautiful state in the nation. But, when the federal government controls two-thirds of Utah, we are extremely limited in what we can do to actively manage and protect our natural resources. We are committed to ensuring that Utahns of all ages and abilities have access to public lands. The BLM has increasingly failed to keep these lands accessible and appears to be pursuing a course of active closure and restriction. It is time for all Utahns to stand for our land.

Putting aside the question of whether Utah really is the most beautiful state in the nation, it will be interesting to see this case play out. Does the federal government have the legal and moral authority to tell states that certain places are simply off limits? Are states sovereign entities, or are they political subdivisions of our national government?

Cox mentioned the recent course of action by the BLM to cut off access to public lands. Under the Biden/Harris administration, the BLM has been attempting to place conservation as a higher value than other uses such as grazing, logging, or mining. Conservatives worry that this could go so far as not allowing any use of public lands at all, even for recreation.

Last January, Rep. Ron Mendive hosted a committee discussion on so-called Natural Asset Companies (NACs), organizations which could potentially take public lands under trust for the purpose of conservation. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was considering allowing NACs to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange, but the proposal was soon withdrawn after questions from elected officials in western states.

Attorney General Raúl Labrador was especially critical:

A Natural Asset Company is the latest fad of environmental activists to get paid for their efforts to control intangible assets like clean air or water, or carbon-scrubbing forests. This is all in the name of fighting climate change and promoting ESG policies – Environmental Social Governance. Instead of intelligent management of our public lands for job-creating efforts like forestry, mining, mineral extraction and recreation, NACs would be locking up public lands and prohibiting productive economic uses.

Proponents of states reclaiming public lands point to these moves by the federal government as evidence that more local control is needed to protect these resources. Last month, Darr Moon, geological engineer, professional civil engineer, and Idaho miner spoke to the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Federalism about how this summer’s massive wildfires were exacerbated by federal mismanagement:

Today, few conservatives contest that it is right and proper for the federal government to administer certain areas such as National Parks and National Monuments. However, what about the millions of acres of land through the west that is still held by the federal government? Is the fact that the federal government controls huge swaths of land west of the Rocky Mountains, yet very little back east, a violation of equal protection?

In 2015, nine years before its current suit, the state of Utah commissioned a study of the relevant laws to determine if there was a legal argument to be made for reclaiming federal lands. The authors of the study found three potential areas in which Utah might be able to prevail:

- Equal Sovereignty Principle

- Equal Footing Doctrine

- Compact Theory

The authors concluded that the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) violated the Equal Sovereignty Principle of the Constitution in that it allowed the federal government to permanently hold on to public lands with no specific use. Under this interpretation, the federal government is treating western states like Utah and Idaho differently than other states which retain nearly full control over their own lands.

The Equal Footing Doctrine says that new states have the same sovereignty as existing states. The authors of the study point out that the original thirteen states, as well as new states such as Texas and Hawaii, each joined the union with full control of their own lands. However, western states such as Utah and Idaho were admitted to the union with the federal government retaining control over vast expanses of land within their borders.

Finally, Compact Theory suggests that statehood created a compact between Utah and the federal government, and gradually returning federal lands to state control was implicit in that contract.

Time will tell if these legal arguments make headway. Undoing decades, even centuries, of federal management of public lands would be a huge undertaking for any court, but the current set of conservative justices have shown a willingness to undo past precedents like Roe v. Wade and Chevron USA v. Natural Resources Defense Council, so perhaps they would be willing to tackle this issue as well.

Not everyone on the right thinks this is a good idea. Just this morning on Twitter, Lafayette Lee asked “If western politicians take back federal land and immediately sell it off to multinational corporations and foreign developers, is it still a win for sovereignty?”

Author, veteran, and Idaho rancher Braxton McCoy echoed that sentiment in a recent podcast where he and his guest worried that the Legislature would be tempted to sell our public lands to Bill Gates, China, or anyone else in exchange for a short term windfall:

These aren’t empty concerns. The Idaho Constitution states that the primary purpose of public lands under state control is to “secure the maximum long term financial return” for the purposes of funding education in our state. If lands currently managed by the BLM or the USFS were to suddenly come under state management, would Idaho be required by our own constitution to sell them to private interests?

[EDIT: Brent Regan pointed something out on Twitter with regards to the constitutional provision regarding state-run public lands: “Idaho Constitution Article IX Section 8 limits the amount of land that can be sold to 100 sections (64,000 acres) per year and no more than 1/2 section to any one buyer. Idaho has 83,642 square miles. 63% is 52,694 square miles of federal land. A section is a square mile. If we sold all the federal lands at the maximum allowed rate it would take 527 YEARS. Because math.”]

On the other hand, Idaho is currently at the mercy of BLM bureaucrats when it comes to our own soil. The federal government has been proceeding toward erecting a massive windmill farm at Lava Ridge to sell so-called “green energy” to Californians, despite nearly unanimous opposition for the people and politicians of Idaho. If Idaho had control of its public lands, then the Lava Ridge Wind Farm would have zero chance of being constructed.

President Donald Trump has been talking about something he calls “Freedom Cities” to be developed in currently unused public lands. If his next administration decides to construct a new city in the Idaho sagebrush, we will surely want to have a say in that, even to the point of vetoing it if necessary.

This week, the Idaho Freedom Caucus (IDFC) announced that it was joining forces with the American Lands Council in support of Utah’s lawsuit seeking the transfer of federal lands to state control. This has implications for Idaho — if Utah prevails, then there will surely be pressure in our state to reclaim our own lands. IDFC co-chair Rep. Heather Scott penned an editorial explaining the decision:

Idaho, like many western states, is both blessed and cursed with federally owned public lands. Although there is ample land for hunting, fishing, recreation, mineral extraction, timber and ranching, excessive amounts of federally owned lands impacts Idaho’s ability to generate necessary local property tax revenues, limits private land ownership, results in a constant potential for dangerous wildfires, and creates friction between the public, state and federal entities when it comes to management.

IDFC vice chair Sen. Brian Lenney expanded on the lawsuit on Twitter, saying “The the feds own more than 60% of Idaho land. And they’re very BAD neighbors.”

Lenney also tweeted an image of a sign restricting access to a fishing spot near his hometown of Nampa:

So which is true? Is federal management of public lands preserving them for productive uses rather than allowing them to be bulldozed and developed? Or is consolidating control of Idaho’s lands in the hands of unaccountable bureaucrats thousands of miles away taking away our right to use and enjoy our own lands?

Perhaps both are true, which makes solving this issue that much more difficult.

In any case, this debate will not be going away any time soon. If the federal government continues down the path of restricting usage and access of public lands, forcing unwelcome projects like Lava Ridge down our throats, and allowing forests to turn into tinderboxes that threaten our citizens, then we in the west will continue to call for local control of these lands. However, men like Lee and McCoy are correct in that there is a risk that our public lands, rather than being set aside for hunting, fishing, grazing, mining, and hiking, would be sold off to private developers once under state control.

We seem to be damned if we do, damned if we don’t.

If Utah prevails in its lawsuit, or if Idaho otherwise begins the process of reclaiming federal lands, perhaps a constitutional amendment could be crafted to preserve the multi-use policies of the BLM and USFS, ensuring continued public access for Idaho ranchers, miners, and citizens. This, of course, would require thorough legal analysis.

One thing is certain: a system that can’t go on forever won’t. Something has to give. Hopefully, this article sparks robust, in-depth discussion of this complex issue, so we as citizens and elected officials can make the best decisions possible. I think we all agree that our posterity deserves to enjoy the pristine and useful lands that we take for granted today.

Thank you all for your support as I continue to bring you news and analysis that empowers you to make positive change in Idaho. Make sure to subscribe, follow me on Twitter, and follow the Chronicle on Facebook, Telegram, YouTube, and Rumble. Have a great weekend!

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.