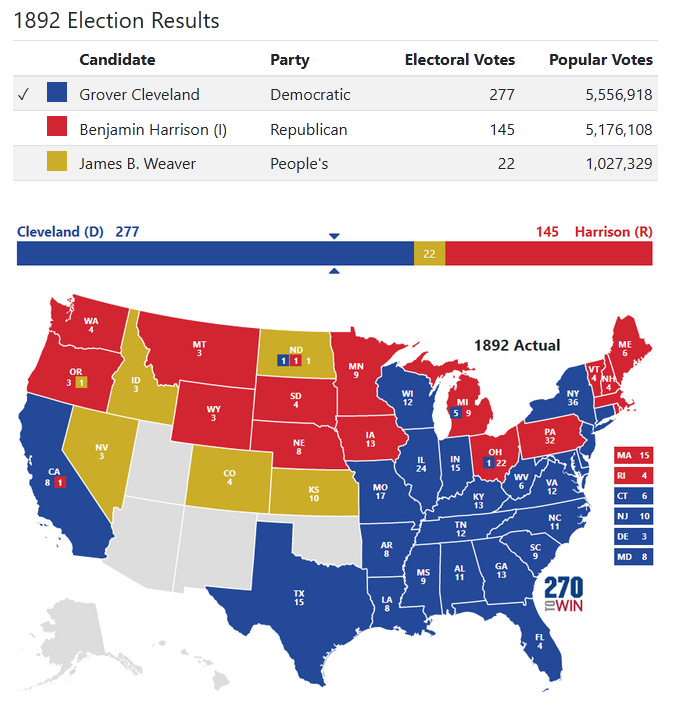

As I continued to research the history of Idaho’s admission to the union and the status of federally-controlled lands in western states, I noticed something interesting. Idaho was admitted to the union in 1890, meaning that the first presidential election our citizens took part in was the 1892 rematch between President Benjamin Harrison and former president Grover Cleveland. However, Idaho voted for neither, opting instead to support James B. Weaver of the Populist Party.

The populism of the late 19th century was mostly a western phenomenon, as farmers, miners, and ranchers sought favorable policies that were generally opposed by the eastern political establishment. Nevertheless, it was in Ocala, Florida, that the platform of the populists was comprehensively laid out.

The Ocala Demands included increasing the money supply, abolishing agricultural futures trading, the coinage of silver, prohibiting foreigners from owning American land, reclaiming land given to railroad companies, repeal of certain tariffs, an income tax, regulation of the press, and the direct election of senators.

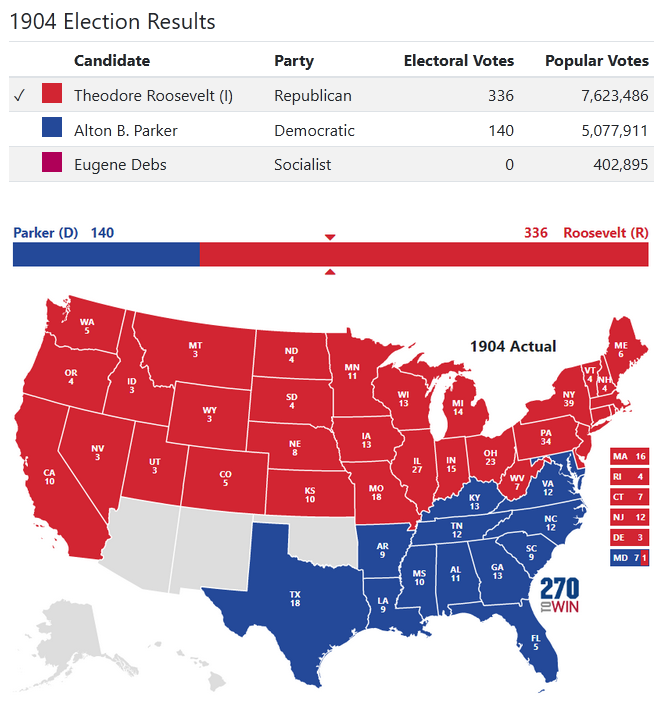

William Jennings Bryan’s takeover of the Democratic Party leading into the 1896 election brought many of these positions into the mainstream. Idaho continued its populist streak, supporting Bryan in 1896 and 1900. However, Republican Theodore Roosevelt championed some of these ideas when he became president following William McKinley’s assassination in 1901, and Idaho followed, supporting Roosevelt in 1904.

Many of the more extreme populists, upset with the way in which the major parties had co-opted their platform, split off into the Socialist Party led by Eugene Debs. However, it was the GOP that grabbed what was left of the populist movement. Senator William Borah exemplified this kind of Republican progressivism of the early 20th century. In 1908, Idaho supported Roosevelt’s handpicked successor William Howard Taft over William Jennings Bryan, but switched to Democrat Woodrow Wilson in 1912 despite Roosevelt campaigning heavily here as the Progressive Party nominee.

From then on, Idaho went with the winner, supporting Republicans like Calvin Coolidge and Democrats like Franklin Roosevelt. From 1904 through 1972, Idaho supported the winning candidate every time. The final time Idaho supported a Democrat for president was in 1964 with Lyndon Johnson, but has been solid red ever since.

All this is to say that Idaho has a history rooted in populism, which is not always the same thing as conservatism.

What is conservatism, anyway? Most people would say it means going back to the way things were before, whether that means the 1990s, the 1950s, or perhaps the 1770s. Others would say it’s a respect for traditional values, small government, and low taxes. Many would point to the Idaho GOP Platform as our current definition of conservatism. Interestingly, the current platform calls for the repeal of the 16th and 17th amendments to the Constitution (income taxes and direct election of senators), both of which were part of the populist plank at the turn of the 20th century.

The question of what separates populism from conservatism today is an interesting one, and entirely separate from the question of what is the right policy to pursue. Just because a policy idea is considered “conservative” does not make it right, nor does a one labeled “populist” make it wrong. For example, I suggest that grocery tax repeal is more populist than conservative, but that doesn’t mean it is necessarily a bad policy.

Wikipedia, for what it’s worth, defines populism as:

…a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of “the people” and often juxtapose this group with “the elite”.It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment.The term developed in the late 19th century and has been applied to various politicians, parties and movements since that time, often as a pejorative.

A common framework for interpreting populism is known as the ideational approach: this defines populism as an ideology that presents “the people” as a morally good force and contrasts them against “the elite”, who are portrayed as corrupt and self-serving. Populists differ in how “the people” are defined, but it can be based along class, ethnic, or national lines. Populists typically present “the elite” as comprising the political, economic, cultural, and media establishment, depicted as a homogeneous entity and accused of placing their own interests, and often the interests of other groups—such as large corporations, foreign countries, or immigrants—above the interests of “the people”.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, this framework placed the farmers, ranchers, and miners of Idaho in opposition to the bankers and industrialists back east. They supported an income tax because they believed it would make wealthy people pay their “fair share” and supported direct election of US senators as a check against party elites that controlled state legislatures.

Today, that paradigm has flipped. The income tax is used to extract money from productive Americans of all classes while the direct election of senators has cut the states out of our federal government entirely. The end result is a huge and unaccountable federal government that has run roughshod over not only our individual liberties, but the very conception of the federal system as laid out in our Constitution.

Populist movements on both the right and the left exploded in the early years of the 21st century in response to both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations. Right wing populism was borne out in the Tea Party movement, which objected to high taxes, bailouts of private corporations, and the federal takeover of the healthcare sector via Obamacare. Left wing populism was seen in the Occupy movement, which cast its followers as the “99%” who opposed the wealthy and powerful who control our economy for their own benefit.

Had these two populist movements worked together, it might have changed history. Conservatives were beginning to be skeptical of big business, while disaffected liberals were starting to see that government could be just as corrupt as corporations. The neoconservative Republican establishment attempted to co-opt the Tea Party, but were unable to stop Donald Trump from seizing the movement and transforming it into MAGA.

On the other hand, the Democratic establishment successfully squashed its own populist uprising. The DNC rigged the 2016 primary for Hillary Clinton, keeping the left wing populist Sen. Bernie Sanders out, and then cleared the deck for Joe Biden in 2020. Sanders meekly kissed the ring and returned to the Democratic fold.

Political realignments happen regularly. Republicans at the turn of the 20th century were generally progressive while Democrats at that time were mostly conservative. Today we are near the end of another realignment. Tea Party / MAGA populism is ascendant in the Republican Party, which has caused neoconservatives like Liz Cheney, Bill Kristol, and John Kasich to align with the Democrats. It’s surreal to see Kamala Harris celebrating the endorsement of Dick Cheney, who was tarred as the devil himself by Democrats in the 2000s. The Occupy movement denounced big corporations, but today’s leftists align with those same big corporations on nearly every issue.

The populist movement within the Republican Party was driven by mounting frustration over how Republican politicians tended to campaign one way but govern another. Nearly all Republicans call themselves conservatives and promise to lower taxes, reduce the size and scope of government, and fight to maintain traditional values. Yet at the end of the day, our government is bigger than ever, taxes and inflation continue to hurt families and businesses, and as for values, conservatives couldn’t even conserve the women’s restroom.

Is it any wonder that the GOP faced a populist revolt? Many in the NeverTrump crowd complain that the MAGA movement is not traditionally conservative, and that the GOP must return to its roots. Yet as Cormac McCarthy wrote, “If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?” Republicans have lied to their voters for so long that they turned to a movement that promised to fight for them instead.

Is it populist to believe that the American government should serve the interests of the American people? Is it populist to believe that citizenship should mean something? Is it populist to believe that it’s not our job to intervene in every foreign conflict? Is it populist to believe that big corporations shouldn’t be allowed to run our lives any more than big government? If those positions are populism, then call me a populist.

What do “conservative” and “progressive” mean in this new age of populism? The linguistic and logistical problem with these labels is that they are relative by definition. Conservatives by nature want to keep things the way they are, or roll them back to the way they were two weeks ago. Progressives, on the other hand, want to change things. What happens when progressives succeed in changing society in the way they want? They become the new conservatives.

I believe the best way forward is a hybrid, a combination of conservatism and populism that presents a positive vision for what we want our society to be. We can’t be bound by specific definitions of “true conservatism” that might have been useful in the past, but by that same token we must remain grounded in the principles of freedom and liberty that made America the greatest nation on earth. We can look to past leaders such as Ronald Reagan for inspiration, but we must also not allow ourselves to be restrained by their specific positions. Our time is not their time; our battles are not their battles. Yet human nature remains the same.

I am pleased to see many of my friends on the right presenting just that sort of positive vision. The Idaho Freedom Foundation has published its 2025 Freedom & Family Agenda, while the Idaho Freedom Caucus crafted a New Vision to Strengthen Idaho. Despite many of us still using the term “conservative” to describe our team, these ideas show that — contrary to leftist propaganda — we are not regressive, we are not merely reactionary, and we have something positive to offer the people of our state and our communities.

These visions are neither purely conservative nor purely populist. Perhaps someone will coin a new label that catches on. For now, most of us will likely continue using the existing terms, which serve more as team mascots than accurate descriptions.

In any case, Idaho’s history shows that its people have long defied political labels. Idahoans have a proud tradition of supporting ideas that benefit society, regardless of the party or politician championing them. As for me, I’m proud to be a member of the party that has embraced this populist moment and is working toward a bright future for all our citizens.

Paid subscribers click over to Substack for a bonus note! Not subscribed? To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.