Last Thursday, I wrote about the Citizen’s Committee on Legislative Compensation and an idea presented by legislative leadership to raise lawmaker pay while eliminating reimbursements for meals. I used that as a springboard to discuss the unequal balance of power between the Legislative and Executive Branches of government and hopefully start a conversation about how to remedy that imbalance.

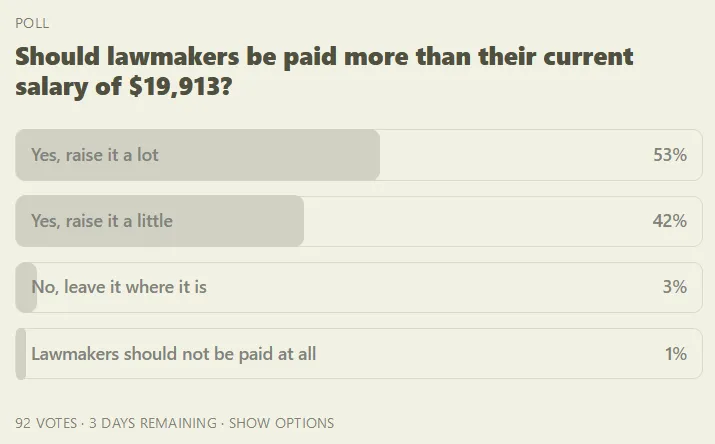

I posted a poll on my previous article asking readers their thoughts on legislative compensation. As of this writing, a large majority of respondents say that lawmakers should be paid more as well as given a budget for staff.

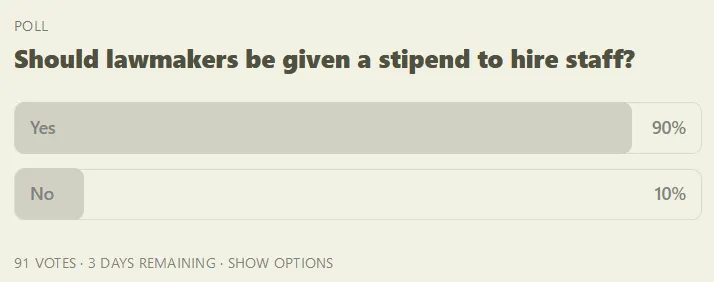

On the other hand, Dustin Hurst ran a poll on Twitter asking if lawmakers should receive a 34% pay raise, which was the number proposed by legislative leadership last week:

He didn’t share how much lawmakers are making right now, so I don’t know if it would have changed the outcome. Nevertheless, the comments below his poll show that many people have strong feelings about this issue. Citizens have grown incredibly cynical about politics, and for good reason. In an age of sky-high inflation and out-of-control government spending, any legislator calling for a pay raise is going to get a harsh reaction, no matter the truth of their current compensation. Yet it remains imperative to approach issues like this from all angles and entertain outside-the-box ideas for cutting government and defending liberty.

Aristotle didn’t actually say “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it,” but I still believe it’s true. I wish more people agreed. I stirred a hornet’s nest last week by merely entertaining the idea of legislative pay raises. One prominent conservative activist called me “statist lite” for daring to even broach the subject, despite me not coming down on any particular side of the debate.

Some of the arguments I heard against raising legislator pay are that they are doing a poor job of reining in government spending, that doing so only makes government bigger, and that lawmakers can’t in good conscience accept more money while regular citizens are struggling under inflation. Those are all reasonable positions.

One other that I saw come up several times is that lawmakers shouldn’t be paid at all, since serving in office is about public service, not getting paid. This one is not so good, I think. This would only further restrict serving in public office to the wealthy, further narrowing the perspective of our Legislature. It reminds me of another debate, that of whether or not churches should pay their pastors. I’ve heard people make the case that pastors should not be paid at all, since the point is to serve God and His people, not draw a paycheck.

Yet if pastors are to serve effectively, they have to pay their own bills. They need a home, food, clothing, and everything else that human beings require in life. The choice churches face is to either pay their pastor a living wage or force him to take a second job, decreasing his ability to minister to his people.

Scripture agrees:

Let the elders who rule well be considered worthy of double honor, especially those who labor in preaching and teaching. For the Scripture says, “You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the grain,” and, “The laborer deserves his wages.”

1 Timothy 5:17-18 ESV

This doesn’t necessarily mean that our legislators should be paid more, and I’m not making that argument. I just happened to notice the similarity.

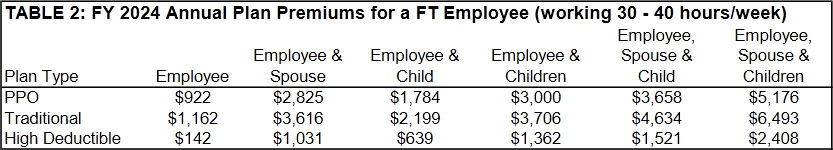

Lawmakers receive more than just cash in compensation. As state employees, representatives and senators are enrolled in PERSI, which is a comparatively generous retirement program, as well as having access to health insurance that costs a fraction of what most people pay in the private sector. According to the legislative budget book, which shows the proposed state budget, lawmakers have the option of purchasing a high deductible healthcare plan for as low as $142 per year:

The Legislature is structurally immune to performance-based bonuses as well. A lawmaker who sits in his or her committee meetings and attends floor sessions but does nothing else gets paid the same as one who works 16 hour days for months on end and then spends the offseason crafting bills, meeting with citizens, and solving problems for their constituents. The only job evaluation that matters comes at the polls, and that often depends on institutional support and skill at campaigning, which is different from the skills necessary to be a good legislator.

Serving in the Legislature can also be a gateway to more lucrative positions. Having “State Representative” or “State Senator” on your resume certainly opens a lot of doors. Most regular people decry the public service to lobbying pipeline, but if some firm offers you six figures after several years of working for peanuts, it would be very hard to say no.

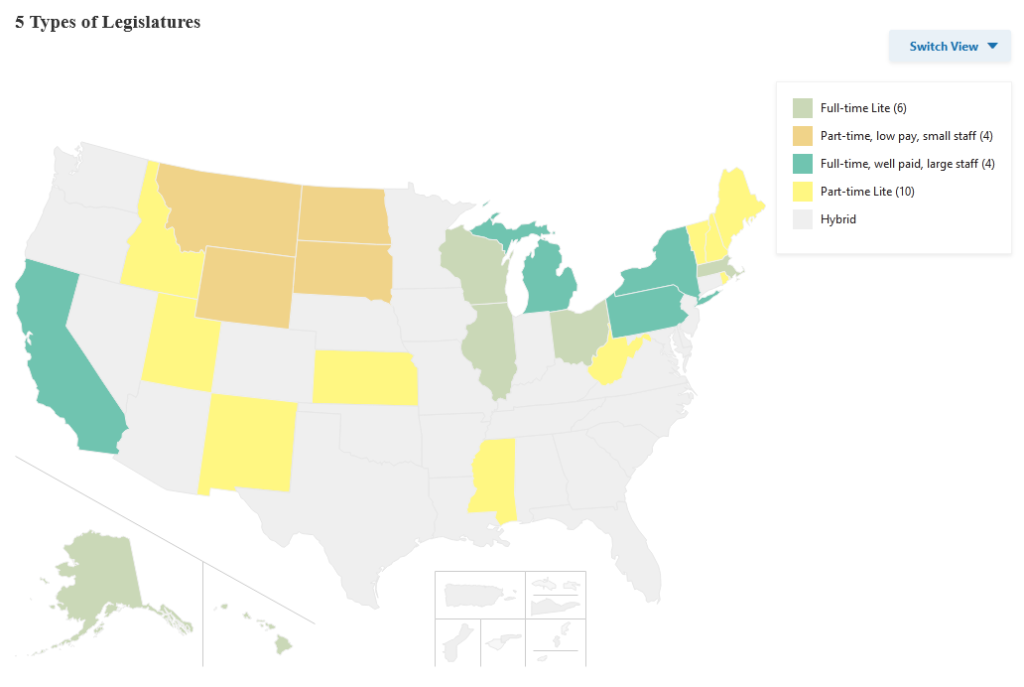

If you’re curious about how other states handle legislative compensation and time on the job, the National Conference of State Legislatures has a good resource. They broke the structure of state legislatures down into three main categories: full time, part time, and hybrid:

There does not seem to be any correlation between whether or not a legislature is full or part time, and how much legislators are paid, and the quality of legislation. Red Ohio and blue Illinois have similar systems, as do blue Oregon and red Florida. More pay and/or a full time Legislature is neither a panacea nor is it the apocalypse.

Regarding the greater question I examined last week, the balance of power between the Legislative and the Executive, even that is difficult to fully quantify. Sen. Phil Hart made a pie chart showing that the Legislature has less than 1/700th the budget of the Executive Branch, but that doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story. Much of the Executive budget is taken up by things like Medicaid payments and operational costs for our state universities.

What about focusing only on taxpayer-funded employees? The highest paid state employee is BSU head coach Spencer Danielson, whose contract gives him more than $1 million a year. College football is it’s own animal entirely, as it brings in quite a lot of money on its own.

Determining exactly how much money is appropriated directly for employees in each branch is not easy, in any case. Precisely what is the Office of the Governor? Is it just the governor and his direct staff, or does it include the various state agencies that report to him? Some quick math to add up each position labeled “Office of the Governor” at Transparent Idaho comes to just over $1.5 million for that office. Gov. Brad Little’s salary of $151,400 is set by statute, as are the other elected constitutional officers.

Attorney General Raúl Labrador earns $146,730 per year, according to statute. His department is large, encompassing the deputy attorneys general who work within other state agencies. Total salaries for the Office of the Attorney General on Transparent Idaho add up to around $20.78 million. The Legislature appropriated $34.36 million and 231 full time positions to the Office in 2023.

On the other hand, the Office of the Lieutenant Governor is tiny. Lt. Gov. Scott Bedke earns $52,990, once again set by statute, and has one part-time employee who earns $43.12 per hour. Assuming the employee works half time, which still might be generous, the Office spends less than $100,000 per year.

I believe that the discussion about money is a proxy for the heart of the matter, which is power and influence. I think most people have cards they’re not showing here. Think tanks and lobbyists on all sides of the spectrum are likely satisfied with the status quo, because right now they play a large role in persuading lawmakers how to vote. Groups as varied as the Idaho Association of Commerce and Industry (IACI), the Farm Bureau, and the Idaho Freedom Foundation (IFF) each urge lawmakers to support or reject certain bills depending on their own priorities, so who wants staff or aides to get in the way?

I happen to think IFF’s analyses are usually on point, but I don’t think lawmakers should rely 100% on any one group when it comes to how they vote. Legislators ideally serve the constitution, their conscience, and their constituents, not think tanks or lobbyists. Each of these outside groups can provide a valuable service in helping lawmakers understand what they’re asked to vote on, but with many hundreds of bills each session it can become overwhelming.

One interesting idea I’ve seen is to empower the Legislature to hire its own legal counsel, outside the attorney general’s office. Art Macomber, who ran for that office in 2022, has drafted a bill that would do just that. In a comment to my original article last Thursday he wrote:

If you circle back to my proposal to give the Senate and the House separate legal offices, you will find it not only removes the power of the executive to influence the laws created by the legislature through opinions, but it also provides attorneys who can review all of IDAPA (722 sets of rules) and then issue reports to the leaders of the legislature every year prior to each session where the legislators could during the session make changes to the body of executive branch rules.

That is not just looking at the new rules as they come from the executive branch every year, which is the untenable method used now, but the whole body of rules needs review and cutting back.

I don’t think Idaho will fix any balance of power issues or separation of power issues by giving the legislators a pay raise, although it may be helpful to draw better representation from the populace. The way to fix a lack of legislative power is to give the legislature more power, so give them their own legal counsel so they can actually monitor the executive branch all year. These would be full-time jobs, partially so there is no need for a full-time legislature.

A little-noticed change spearheaded by Speaker Mike Moyle last year actually did a lot of good. Prior to 2024, bureaucratic rule changes only needed to pass one chamber of the Legislature to go into effect, meaning the Senate could pass a rule that the House rejected and it would still gain the force of law. This changed in 2024 — now both chambers must concur, as is the case for all laws. This at least brings an extra set of eyes to any proposed rule.

It’s easy to say our lawmakers should just vote better, stick to their principles, and show courage, but what does that mean when scrutinizing a 40 page bill or rule change to make sure there are no poison pills or unintended consequences? Legislators sit on two or three committees, working on their own bills as well as considering dozens or even hundreds of others, while still answering emails and phone calls, and meeting with constituents, lobbyists, and colleagues. It’s a busy job, and details can easily be missed.

Early in the 2023 session, the Senate Health & Welfare Committee approved a rule change for the Idaho Child Care Program (ICCP) that raised the eligibility threshold for families to receive federal subsidies. This change was one reason why the program has become structurally over budget, yet conservatives on the committee voted in favor of the rule. Why? I presume it was because they were new to the game, inundated with a tremendous amount of work, and missed some important details.

Lauren Walker, a conservative activist from North Idaho, spent much of the 2023 session as a volunteer in the Capitol. She shared her first hand perspective in response to my original article last Thursday:

I saw 1 aide for every 3 Senators when I was down there- and worked side by side half the time- and they were overloaded. The House? Forget about it. There was a room of over 30 Reps and supposedly there was one aide who was in another part of the building whom I never laid eyes on the entire session.

This is scary bc it’s the primary reason things slip through in bills and go unnoticed. There’s hundreds of bills rolling through there each session, impossible to read them all, and sometimes I think the overload is intentional to sneak in bill language (not for the good). There’s been remote bill reading teams for the last few sessions that don’t get paid to try to catch this.

But every executive spot has a full entourage of help. It’s EXTREMELY unbalanced. I would say don’t touch the pay, reduce executive staff, budget for 1 aide for every 1-2 legislators. People don’t understand how difficult those 3 months are until they see it first hand.

Also- your legislature is super accessible. Pick your favorite senator/rep and volunteer for a week or more at the capitol to help them. You’ll get a firehose civics lesson, and you’ll be their favorite person on earth. Even if it’s just freeing them up by answering phones/emails. Bonus points if you read bills and spot poison pills in them.

The question I’m examining is not how to further grow government, but how to make our lawmakers (especially conservatives) more effective in their jobs. Rep. Heather Scott presented an interesting idea over the weekend about how artificial intelligence (AI) might help:

As an experiment, I prompted AI to help me with that same 12-15 per hour a month task of organizing and simplifying the thousands of pages of rules regulations and fees. And not just for one month’s data, but for the monthly changes made from January to October.

And guess how much time it took me?

- 3 minutes to find the monthly administrative rules, regulations and fees website

- 3 minutes to upload the documents for analysis

- 2 minutes to get the analysis

- 1 minute to save the document

For less than 10 minutes of my time, I was able to prepare what would have taken possibly 180 hours, or seven and a half (24-hour) days.

Obviously we must be careful with the way in which we utilize AI tools such as ChatGPT. Large language models (LLMs) tend to tell you what you want to hear, not always what is true or factual. However, they can do a great job of summarizing large amounts of information. I routinely use ChatGPT to summarize things like Supreme Court decisions or the full text of state laws. Earlier in this essay I linked to the Idaho statue regarding salaries for constitutional officers. At first, I searched the statutes for “salaries” but found that pointless, so I asked ChatGPT to direct me to the title and chapter in question and it succeeded in the blink of an eye.

So long as you double check the facts before using them, LLMs can be a huge time saver when it comes to research. There’s nothing stopping a legislator from uploading the PDF of a bill to ChatGPT and asking it to highlight any potential poison pills or unintended consequences. Could this be a solution to the imbalance of power in our government?

AI might be able to solve another potential problem in the Capitol, that of the Legislative Services Office (LSO). When a lawmaker needs to draft a bill, he or she sends it to LSO, who puts in the language and syntax necessary for it to conform to the proper standard. However, I have heard anecdotally from numerous people that some within LSO resist conservative ideas, to the point where they insert poison pills or water down language that a lawmaker requested. Considering that LSO essentially acts as the gatekeeper to legislation, this is a serious concern.

What if you didn’t need LSO to fix the structure and syntax of a bill? What if AI could help you instead? I used ChatGPT to help with the structure of my resolution calling for no candidate withdrawals after the primary. The actual wording was entirely my own, but I asked ChatGPT to give me an outline from which to start. Why not do the same thing with legislation? LLMs could also quickly tell a bill author exactly what sections of law need to be amended to accomplish a particular goal.

Perhaps a combination of volunteers and AI tools can change the game for conservative lawmakers without requiring more taxpayer money. As before, I’m not coming down in favor of any particular solution, rather I am trying to think outside the box. The only thing of which I’m sure is that continuing to do the same thing will not result in a different outcome, so let’s put all our cards on the table and come up with a solution that will actually accomplish our shared goals. We all want to cut government, we all want to defend liberty, so let’s do whatever we can to make it happen.

There’s a special bonus note for paid subscribers over at Substack, so check it out. Not subscribed? Sign up for free to get daily posts in your inbox, or support my work and get access to special content!

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.