Earlier this week, Fred Birnbaum of the Idaho Freedom Foundation published an article laying out what he called a road map for ending property taxes in Idaho. He explained that despite the Legislature cutting $4.6 billion in taxes over the past five years, tax revenue has nevertheless increased by 46% from 2019 to 2023:

That’s over 2.5 times the increase in the consumer price index, the most common measure of inflation. And yes, the population has increased about 8% over the same period, so when we add inflation to population, it sums to about 26%.

Yet even with the tax cuts, total tax collections are up 46%. These are differences that matter: tax collections are nearly double what inflation and population growth would dictate.

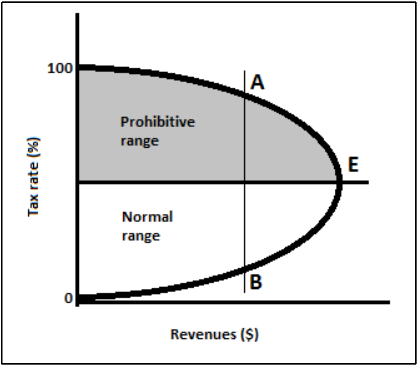

It is tempting to think of tax rates and tax revenues as being perfectly correlated with each other, but there are many factors that affect how much revenue a government can extract from its citizens. In a growing economy, people tend to make more money and also buy more things, both of which increase government revenues from income and sales taxes. This can occur even if tax rates go down, which is clearly what happened in Idaho from 2019-2023.

Tax rates also alter behavior. If Idaho was to eliminate the 6% sales tax on groceries, it logically follows that many families would be able to increase their grocery budgets by a commensurate amount. Similarly, when income taxes go up, employees might look to decrease their total working hours since the additional labor is not worth the smaller paycheck.

Economist Arthur Laffer identified this phenomenon many years ago. The Laffer Curve shows how there is an ideal tax rate that will maximize tax revenues:

Idaho is certainly not hurting for cash. The increase in tax revenues has enabled Gov. Brad Little and the Legislature to cut taxes nearly every year since 2019 while not having to worry about finding ways to cut spending to make up the difference. Talk about having your cake and eating it too!

Birnbaum explained that had the state limited taxation to a 26% increase from 2019 to 2023, rather than the 46% we saw, total revenues would have dropped from $9.5 billion to $8.2 billion, a difference large enough to offset approximately 60% of property taxes.

Logan Finney of Idaho Public TV questioned Birnbaum’s proposal on Twitter, pointing out that Rep. Jason Monks has long suggested that property taxes could be eliminated entirely simply by raising the state sales tax from 6% to 11%.

Birnbaum replied by saying that the point was to offset property taxes without raising sales taxes by reducing spending instead.

In his article, Birnbaum pointed out that total state appropriations (excluding federal, county, and local expenditures) increased from $5.4 billion in 2019 to $7.4 billion in 2023. However, had state spending been capped by the same 26% number (inflation plus population growth), the fiscal year 2023 expenditures would be $6.8 billion instead. Rather than shuffling the extra $600 million in revenues into a rainy day fund or new project, the state could have added it to the existing $300 million in revenue sharing the state already used for property tax relief.

Birnbaum said that if the state had started capping its spending earlier, such as in 2014, the resulting savings could have eliminated property taxes entirely.

House Bill 292, passed in 2023, created something called a surplus eliminator. A portion of any tax revenue that goes above and beyond budgeted expenditures is returned to the citizens in the form of property tax relief. This led to a return of $300 million to property owners in 2023 and $76.5 million upcoming in 2024.

What would eliminating property taxes in Idaho look like? As Birnbaum explained, the state could reduce spending and use the remaining funds to support the budgets of taxing districts that currently rely on property taxes. These include cities, counties, school districts, library districts, fire districts, and others. However, if the state were to simply transfer money to these districts to cover their existing budgets, it would reward those with excessive spending habits while penalizing cities and counties that have been more fiscally responsible.

When I asked Fred about this, he suggested the state could possibly commission a study to benchmark local spending — determining, for example, how much cities spend on public safety or public works per citizen. The state could then provide funding based on these averages, allowing taxing districts to seek voter approval for anything above that amount. Cities like Boise and Meridian could ask their residents for consent to maintain their big spending, while more frugal communities could be content with what they receive from the state.

In the end, it’s all our money. Figuring out the most efficient and most moral way to appropriate tax dollars is a primary duty of our elected officials. Cutting taxes and reining in spending are both necessary not only to keep our own money in our own pockets, but also to curb the growth of government which continually threatens our liberties.

We need big ideas if we are to move toward a fairer society, and Birnbaum’s article lays out a logical path toward eliminating perhaps the most unfair tax of them all. Read the whole thing and ask your legislators to read it too.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.