Last spring, Gov. Brad Little finally signed “that stinkin’ library bill” into law. House Bill 710 requires schools and public libraries to have a policy regarding material that is defined by Idaho Code to be harmful to minors as as well as a form to allow citizens to request review of library materials.

The definitions of what is considered harmful to minors is laid out in Idaho Code 18-1514, which was originally created in 1972, and most recently adjusted via H710 this year. The biggest hurdle remaining in the law is this passage:

Nothing herein contained is intended to include or proscribe any matter which, when considered as a whole, and in context in which it is used, possesses serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value for minors.

Who decides what is considered “serious literary value for minors”? It’s first up to the school or library board that is reviewing challenged books, and then up to a judge after that. This means that a library board in Boise will surely come to different conclusions than one in Eagle. Conservatives argue (and I generally agree) that no amount of “literary value” can outweigh the harm caused by exposing children to explicit depictions of sexual situations. The other side argues that keeping children, or teenagers, from these materials is in itself harmful because they need to understand what real life is like, especially as they might be working through harmful situations in real life.

These two sides are clearly dug in, and there can be little understanding when we have such distinct worldviews. I would like to look at a deeper issue, therefore, one that is driving this debate: Why do so many books marketed toward teenagers contain graphic depictions of sexual situations?

On Wednesday night, I joined my colleagues on the Eagle Library Board of Trustees to decide what to do with 25 books that were challenged under the new law. While it’s great that members of the community stepped up to try and protect children, there is some confusion about the letter of the law. The civil cause of action allowed by the new law technically only applies to a child under 18 who obtained material that is considered harmful to minors or the parent of a child who obtained such material. Some of the citizens who submitted forms did not appear to meet that criteria; nevertheless we decided to evaluate all of the challenged books.

We deliberated over the books in an executive session, because of the possibility of litigation depending on our decision. I can’t tell you the details of that discussion, but after we returned to the public meeting we voted to move twenty-two books from the teen section to the adult section, and three more off the floor and replaced with dummy copies in case adults want to check them out.

We also voted to implement a tiered library card system, allowing parents to opt-in to giving their children or teenagers restricted cards that will not allow them to check out adult materials. I believe this combination of actions will significantly decrease the chances of children coming across explicit sexual materials in the library.

Some of the 25 books we evaluated were especially heinous, while others seemed to use a lot of profanity and sexual expressions in the dialogue. Several books by author Sarah J. Maas were included in the list, part of a series of young adult fantasy/romance novels that have been popular lately. The newer books apparently contain extended sexual scenes, which calls into question the audience to whom these books are marketed. Before the meeting I said to our library director that I thought most of the people checking out these books were likely twenty-something women rather than teenagers, and he agreed.

I went to a Barnes and Noble in Boise this afternoon to see where some of these books were placed. The young adult section was filled with teen romance, often with LGBTQ+ themes, while the young adult sci-fi/fantasy section was full of the sort of romance novels that have a veneer of fantasy, such as the Twilight series. I couldn’t find any of the books by Sarah Maas until I turned around and found an entire pillar devoted to them:

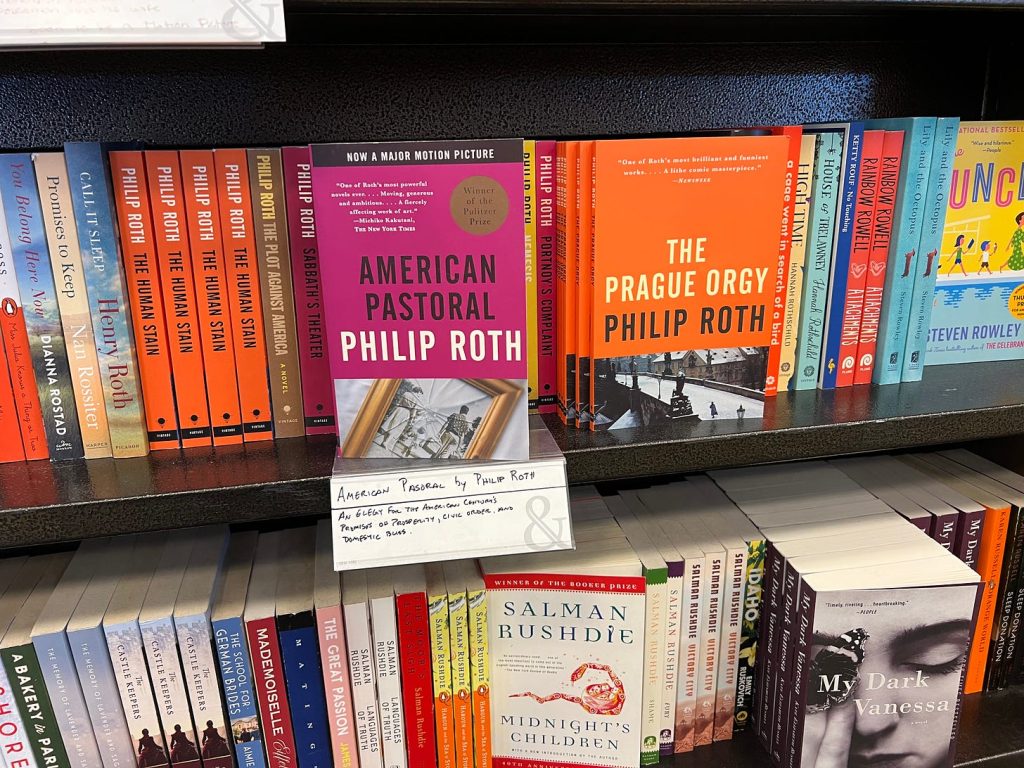

One of the three books our board considered so explicit as to move off the library floor entirely was Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, which is apparently full of explicit sexual language. I found it at Barnes & Noble as well:

This raises the question: If the sexual content in these books fits the definition of materials harmful to minors in Idaho Code, then why is a bookstore allowed to keep them on its shelves where any child can wander by and flip through them?

On the other hand, if it doesn’t fit that definition, then what course of action should Idaho library boards take in light of the letter of the law?

This is why I think the problem is bigger than even the most zealous crusaders think. As library trustees, we can examine individual books and decide on which shelves they belong, but authors and publishers continue to crank out books like this with sexually explicit language and scenarios faster than we can keep up. I can’t read every book that goes on our library’s shelves, and neither can the staff. We’re all trusting in third parties — publishers, review journals, subscription services, or websites like Moms4Liberty or Booklooks — to tell us what is out there.

- We must ask why authors and publishers are putting these ideas into books that are then marketed toward teenagers. When did we as a society decide it was normal for novels read by 13-year-old girls to contain explicit sex scenes?

- We must clearly define what the law is able to accomplish. Having closely studied the law for several months now in the process of my duties as a library trustee, I see a dozen different ways in which a savvy defense attorney could defeat attempts to bring injunctive relief to parents concerned about materials in their child’s school or public library. Can the law be made stronger? Probably, but then would the authors just get sneakier and the lawyers get savvier?

- We must decide what we as communities want to promote. There are many books in the library that, while not containing scenes as explicit as Sarah Maas’ works, promote values that many Christians and conservatives believe are contrary to a healthy society. Fixing that requires more than filling out a form on a library website, it requires a revolutionary change in the direction our society is going, starting in our families and communities.

I will continue to do the best I can as a trustee of the public library to make it a safe and welcoming place for children. I have been a cardholder of the public library since I was ten, and it has always been a positive place for me and so many others. Yet keeping the sickness of our society off its shelves is going to take a lot more work than many of us thought.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.