The last time I wrote about calls for an Article V Convention, I lost a few subscribers, and a senior vice president of Convention of States Action wrote an op-ed attempting to refute my concerns. Last spring, a leader of Idaho’s Convention of States organization spent two hours trying to convince me of his position and seemed offended when I remained steadfast in my views.

With two Article V resolutions working their way through the Legislature this month, I am once again compelled to wade into those stormy waters and share my thoughts on why I believe the push for a convention is misguided.

This is an extremely frustrating issue because I believe there are good people on both sides. Nevertheless, supporters of an Article V Convention are often extremely zealous in their advocacy, and I’ve seen good people—and myself—smeared as RINOs or even traitors for refusing to join their crusade.

To review: Article V of the Constitution lays out how the document can be altered:

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, or, on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which, in either case, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of this Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Congress; provided that no amendment which may be made prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any manner affect the first and fourth clauses in the ninth section of the first article; and that no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate.

The Constitution has been amended 27 times since its ratification. Eleven of those amendments came out of the First Congress, following promises made during the ratification process to adopt a Bill of Rights. One of those original amendments, which prohibited Congress from voting itself a pay increase, languished until 1992, when it was finally ratified by enough states.

In each of these cases, amendments were proposed by two-thirds of Congress and then ratified by three-fourths of the states. The second method of amending the Constitution—where Congress would call a convention after being petitioned by two-thirds of the states—has never been used.

My biggest concern with this idea is simply that it has never been done before, which means any assurances about how it would proceed are inherently speculative. Proponents dismiss concerns by claiming that case law or specific provisions would ensure the process unfolds exactly as intended, but life is rarely that neat and tidy. Indeed, one of the strongest arguments against a convention is that the original Constitution itself was drafted by a convention that had been called merely to amend the Articles of Confederation.

I won’t rehash the arguments I and others have already made. If you want to read more, you can find them here:

- A Convention of States is Not the Answer by Dorothy Moon on 1/29/26

- Additional Concerns About an Article V Convention by Brian Almon on 2/21/25

- Why I Don’t Support a Convention of States by Brian Almon on 2/17/25

- Convention of the States is Likely to Disappoint Conservatives by Fred Birnbaum on 8/15/23

- We Can Restrain the Federal Government Without a Convention of States by Wayne Hoffman on 1/31/23

- Turning to a Convention of States in Times of National Crisis is Not the Answer by Dorothy Moon on 1/4/23

- Convention of States is a Fool’s Gambit by Ron Nate on 7/25/22

If you want to read arguments in favor, check out Convention of States Action, US Term Limits, or Balanced Budget Now.

This year’s proposals come via resolutions sponsored by Reps. John Shirts and Josh Tanner. House Concurrent Resolution 23 calls for a convention to draft an amendment related to congressional term limits, while House Concurrent Resolution 25 calls for a convention to propose a balanced budget amendment.

An attempt to sign Idaho onto a call for an Article V Convention failed last year by a vote of 26–44. Rep. Bruce Skaug, who supported that effort, asked in committee last week why this year’s attempt would be any different. Rep. Tanner responded that splitting the issues into separate resolutions gave each a better chance of passing. Rep. Shirts’s resolution goes even further, explicitly referencing a “33-state strategy” intended to pressure Congress into passing a balanced budget amendment without actually convening a convention.

Loren Enns, president of Balanced Budget Now, testified in favor of HCR25 this morning, saying the goal was not to hold a convention, but to reach 33 states—one short of the number required to compel Congress to call one. This, he argued, would force Congress to pass the amendment itself.

One question I wish committee members had asked is: what if Congress calls your bluff? If you are explicitly saying you have no intention of actually convening a convention to propose amendments, how does that force Congress to act? It’s like going all in at the poker table holding an off-suit seven and two. You might scare your opponent into folding—but what if you’re wrong?

Proponents of the “threaten Congress” strategy argue that similar pressure tactics have worked in the past, but my reading suggests there is disagreement on that point. The Bill of Rights emerged from agreements made during the original ratification process, meaning Article V was not yet in force at the time. Every other amendment originated directly in Congress. The only amendment that can plausibly be tied to the threat of state conventions is the 17th Amendment, which required senators to be directly elected rather than appointed by state legislatures.

This is especially ironic, in my view. Enns claimed in his testimony that Article V was meant to serve as a check by the states against centralized power, but in reality it was the Senate that historically fulfilled that role—until the 17th Amendment severed the states’ direct influence over the federal government.

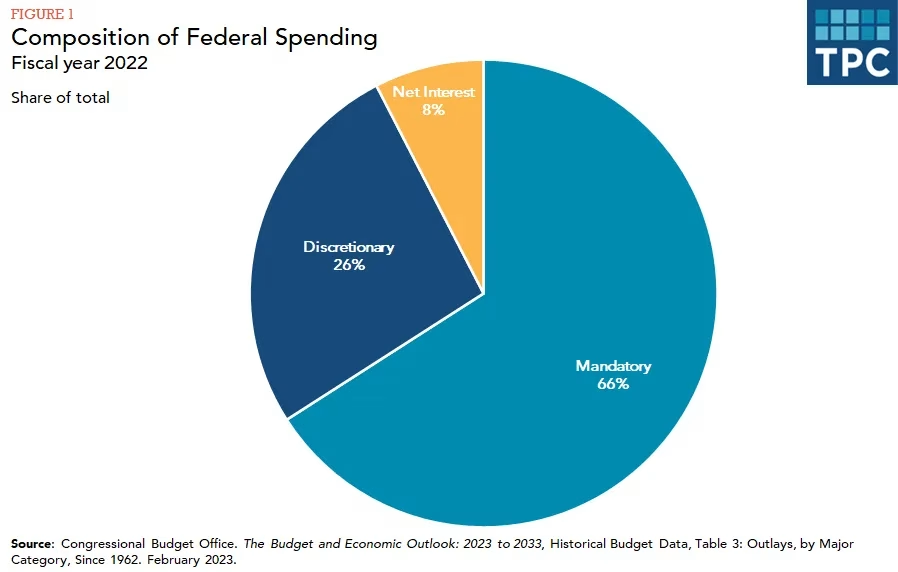

This is just one of many ways structural problems have become deeply embedded in our system. The administrative state has grown large and powerful over the past century, and Congress increasingly delegates its lawmaking authority to unelected bureaucrats. Federal spending is out of control, but roughly two-thirds of the budget is mandatory—set by statute and mostly out of reach of congressional budget writers.

Many Republicans speak in general terms about reining in federal spending, but few appear willing to do what that would actually require. Balancing the budget would mean slashing Medicare, Medicaid, and other welfare programs, as well as sharply reducing funds sent to the states. Thirty-seven percent of Idaho’s FY2026 budget comes from federal dollars. Are we prepared to backfill that with our own state tax dollars, or eliminate those programs altogether? I personally support making large cuts to government spending, and I suspect you do as well, but a great many voters would balk at such a plan.

The other option for Congress would be raising taxes, and surely no Republicans want that.

The Article V Convention—whether as a bluff or a sincere effort—strikes me as a mythical “fix everything button.” It feels like a Hail Mary pass, an attempt to solve every problem at once and then ride off into the sunset. That’s not how life works, and it’s not how politics works. We are not going to fix every problem quickly, or perhaps even within our lifetimes. Our responsibility is to do the best we can with the circumstances we face and, hopefully, leave the country in better shape for the next generation.

If you support an Article V Convention, I hope you read this in the tradition of spirited debate—iron sharpening iron. This issue cuts across factional lines, with people I deeply respect on both sides. I hope we can engage in a productive discussion about how to move our country in the right direction without impugning one another’s motives, resorting to name-calling, or trying to push dissenters out of polite society.

I believe the time, energy, and money being devoted to the Article V Convention would be better spent elsewhere, but I’m not going to castigate those who support it. We all want to leave our nation better than we found it, so let’s have productive conversations and get to work.

Feature image created with Microsoft Copilot

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.