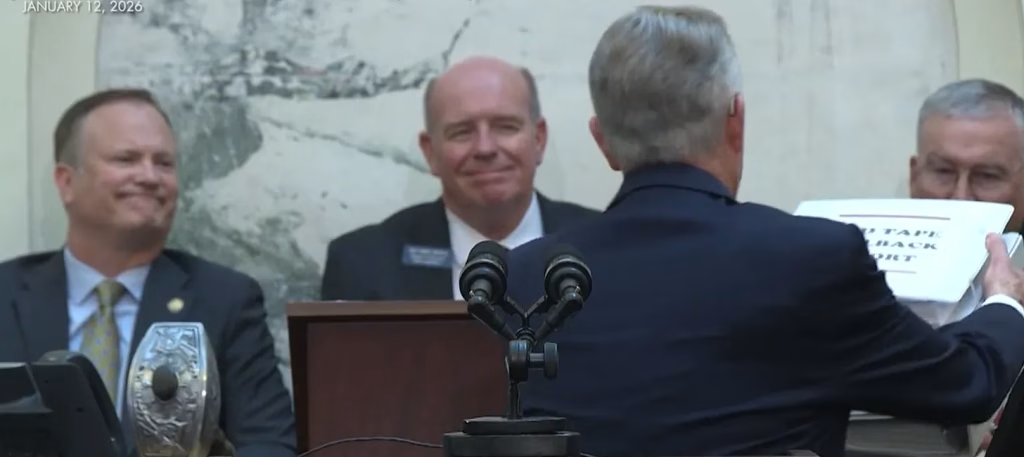

Remember that moment in Gov. Brad Little’s State of the State Address last week when he plopped a stack of binders in front of Lt. Gov. Scott Bedke and House Speaker Mike Moyle, calling it the “Red Tape Rollback Plan” and promising it would eliminate 145,000 words from state law?

Moyle was rather nonplussed, later remarking that while it was a cool prop, there were “issues” in the binders. He said his staff was reviewing them and had already found errors or sections of code that should not be repealed. I managed to get hold of the first 50 pages of the plan and have been sifting through them for the past few days.

To understand how we got here, we have to look back over the past seven years and understand the distinction between law, which is found in Idaho Code, and bureaucratic rules, which are found in the Idaho Administrative Procedures Act (IDAPA).

I wrote about IDAPA last year:

In theory, Idaho has a part-time Legislature, with lawmakers coming to Boise in January and going home in April. In reality, however, we have a full-time lawmaking body — scores of them, in fact. The Executive Branch of Idaho’s government includes 189 departments, divisions, and agencies, many of which have rulemaking authority delegated by the Legislature. This authority is detailed in Title 67, Chapter 52 of Idaho Code, known as the Idaho Administrative Procedure Act (IDAPA).

…

Rules promulgated by these administrative agencies carry the force of law. New rules must be authorized by the Legislature each year, but temporary rules created between sessions are just as valid.

What this means is that the Legislature passes laws, according to its constitutional authority delegated to it by the people of Idaho. The executive branch—the bureaucracy—is charged with executing those laws and is authorized to promulgate rules to guide how that is done. These rules carry the force of law.

Both Idaho Code and IDAPA rules tend to grow unchecked, like kudzu, or computer code. Like an application that becomes more complex as programmers add more functions, these bodies of law become more labyrinthine over time. Cutting outdated and obsolete sections of statute and rule is a constant battle, but one that both the governor and the Legislature have been focused on for several years.

Although many conservatives are unable to forgive Gov. Little for the actions he took during the COVID-19 pandemic, I’m sure he would like his legacy to be cutting bureaucratic rules and regulations, investing in public education, and the Idaho LAUNCH program. The year 2019—Little’s one full year in office between his election and the lockdowns—was all about cutting red tape. In January 2020, Little signed Executive Order 2020-01, establishing zero-based regulation for all state agencies. Under that order, every administrative rule had to be reviewed by the Legislature over a seven-year period to determine whether it was worth keeping.

That order followed an unlikely series of events in 2019, when the Legislature failed to pass a bill codifying administrative rules. As a result, every rule was set to expire. The governor then had the opportunity to pick and choose which rules would be marked as temporary—keeping them in place until the next session—and which would be allowed to lapse. By the end of the year, Little boasted that Idaho had cut or simplified 75% of its bureaucratic regulations.

If you ask members of the Legislature, they might say this never would have happened without their actions, while the governor’s office might say it was Little’s initiative. As I’ve said before, I don’t care who takes credit so long as things get done. Cutting and consolidating administrative rules is a noble endeavor no matter who is doing it.

The Legislature then went on to change the rules surrounding the rules themselves. House Bill 206 in the 2023 session, which passed on a mostly party-line vote, allows either chamber to reject a proposed administrative rule, rather than allowing rules to advance through only one chamber as before. This means that two germane committees—one in the House and one in the Senate—must review and approve each permanent rule before it goes into effect.

The 2025 session saw further action to move administrative rules into statute, giving elected legislators even more direct control over regulations that carry the force of law. That was why I wrote about it at the time. It was—and still is—a laudable goal to bring these rules under the direct purview of our lawmaking body.

House Bill 14 last year began the process of cleaning up Idaho Code itself, in addition to administrative rules. The Code Cleanup Act required state agencies to review their own enabling statutes—the portions of Idaho Code that created and authorized them—and identify anything that was outdated, obsolete, or otherwise unnecessary. The DOGE Task Force worked closely with agencies in this process.

The governor’s three binders of recommendations represent the next step. I obtained about fifty pages from one of the binders, consisting of a matrix of Idaho Code sections, determinations of their relevance, explanations for those determinations, whether each section should be repealed in whole, and the agency to which it is connected.

I scanned the packet, which you can read here. Apologies for the copy quality.

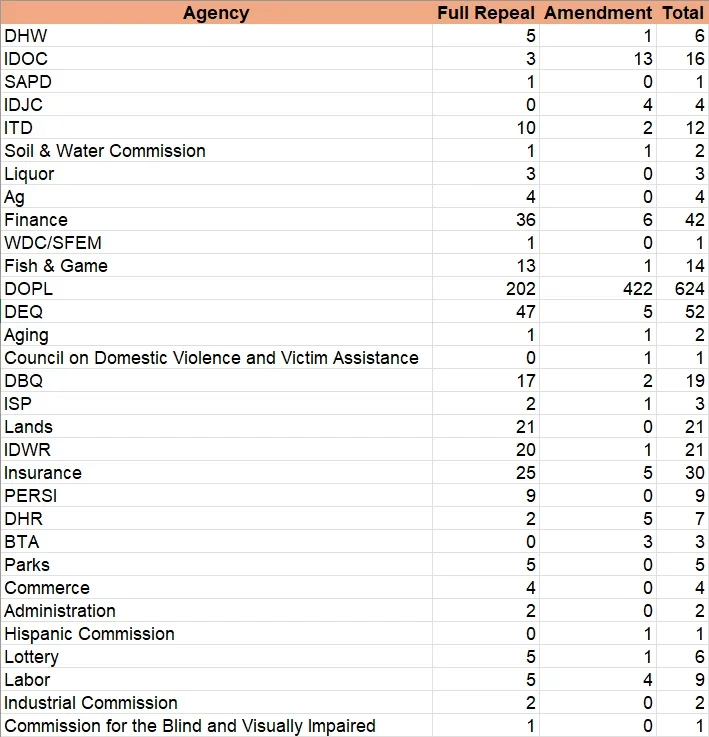

It’s a lot to read. I ran it through Grok—take that with the usual grain of salt—which counted 895 sections of code identified, with 481 proposed amendments and 414 marked for repeal. I asked it to break the recommendations down by agency, and this was the result:

As you can see, DOPL—the Division of Occupational and Professional Licenses—accounts for the lion’s share of the proposed cuts. I picked a few of the DOPL changes at random for a closer look.

Idaho Code § 54-204(1)(j), which is marked as “unnecessary,” appears in the section outlining the powers and duties of the Idaho State Board of Accountancy. It reads:

Such other rules as the board may deem necessary or appropriate to implement or administer the provisions and purposes of this chapter.

The governor’s recommendation is to remove it as it does not “effect public health, safety, or welfare.”

Other such recommendations include Idaho Code § 54-204 (5), which says:

To authorize by written agreement the division of occupational and professional licenses as agent to act in its interest.

The sheet points to Idaho Code § 54-204 (6) as being outdated, classifying it as “outdated for being duplicative and/or not aligning with modern regulatory practices”. That line says:

Any action, claim or demand to recover money damages from the board or its employees which any person is legally entitled to recover as compensation for the negligent or otherwise wrongful act or omission of the board or its employees, when acting within the course and scope of their employment, shall be governed by the Idaho tort claims act, chapter 9, title 6, Idaho Code. For purposes of this subsection, the term “employees” shall include special assignment members of the board and other independent contractors while acting within the course and scope of their board related work.

The next paragraph is also listed as outdated:

All hearings, investigations or proceedings conducted by the board shall be conducted in conformity with chapter 52, title 67, Idaho Code, and rules of the board adopted pursuant thereto, and, unless otherwise requested by the concerned party, be subject to disclosure according to chapter 1, title 74, Idaho Code.

That’s just a random sampling of the hundreds of lines of DOPL code referenced in the binder. I can only speculate as to exactly why some of these sections are deemed unnecessary or outdated. I do know that DOPL’s statutory and regulatory framework is incredibly complex and convoluted.

Incidentally, just this morning I watched Rep. Jordan Redman present an RS to the House State Affairs Committee. Chairman Brent Crane joked about the size of the packet—apparently the legislation would consolidate everything in DOPL code related to disciplinary actions into a single section, which explains the amount of paper. Now that it has been printed as House Bill 505, I see that the title alone spans more than three pages.

Rep. Redman’s initiative, separate from the governor’s recommendations, builds on last year’s H14 and the work of the DOGE Task Force. It consolidates disciplinary provisions into a single section of code, which not only trims the statute but also standardizes procedures across occupational licensing agencies. For citizens, that makes the law easier to read and establishes consistent expectations across professions.

Beyond the question of whether or not DOPL should exist at all, this is a good thing. Going forward, the Legislature and the executive branch should continue to regularly reform and maintain both administrative rules and state law so that we don’t have to cut another 145,000 words decades from now.

As necessary as this process is, we should be careful not to oversell it. This effort will not deliver structural reform to government itself, nor roll back the growth of government to its proper size and scope. That requires additional legislation. Still, cleaning up the code is essential work and should draw support from all sides. Recall that H14 passed unanimously in 2025.

Watch for more code cleanup bills this year. It’s tedious but necessary work. The average citizen should be able to read and understand the law to which he is held accountable, so I applaud these initiatives.

Feature image created with Microsoft Copilot.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.