Last week, Idaho GOP chairwoman Dorothy Moon wrote an op-ed in support of the Parental Choice Tax Credit and in opposition to those suing to block access to it. She cited the “nation’s report card” from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which showed that less than half of Idaho students are proficient in math:

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), only 41% of Idaho 4th graders are proficient in math, and just 31% of 8th graders tested as proficient. While the NAEP notes that Idaho is above the national average, that’s not saying much. Idaho taxpayers spend roughly $3 billion a year on K‑12 public schools, and results like this are unacceptable.

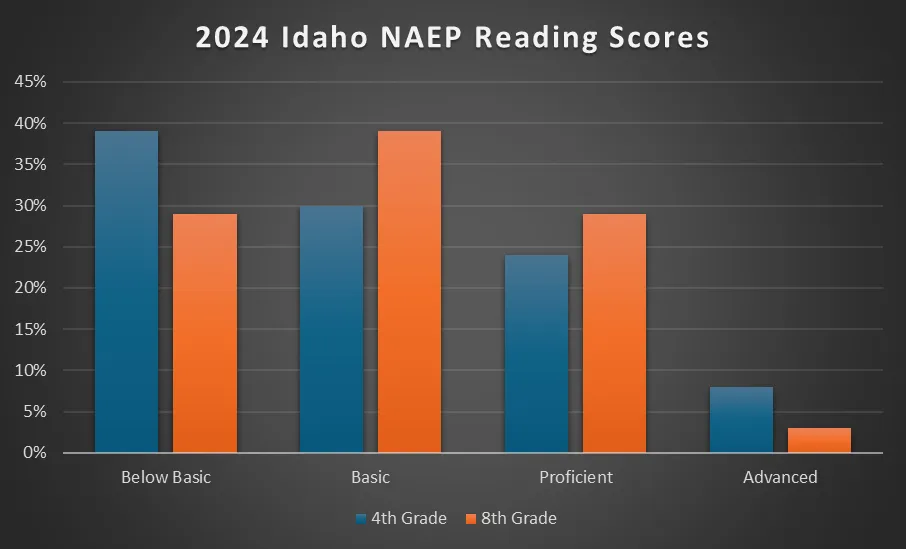

Math is important, but as a writer, I was curious about reading scores as well. After all, language is how we communicate and build a society. Unfortunately, NAEP reading scores are just as abysmal as math scores.

In 2024, 32% of Idaho 4th graders scored as “proficient” or “advanced.” 8th graders hit the same mark. In both cases, Idahoans were above the national average, which, as Moon pointed out, isn’t saying much.

I was curious as to what those terms mean. Here is NAEP’s rubric for 4th graders:

- Basic: Sequence or categorize events from a literary text.

- Proficient: Provide an opinion using relevant information from the text.

- Advanced: Distinguish the theme of a text.

Here are the metrics for 8th graders:

- Basic: Identify basic literary elements such as the order of events, character traits, and main idea.

- Proficient: Identify one or both sides of an argument in an informational text.

- Advanced: Use text evidence from multiple sources to substantiate claims made by an author.

Consider the ramifications of these scores. More than two-thirds of Idaho 4th graders cannot understand a text well enough to develop an opinion. More than two-thirds of Idaho 8th graders cannot identify one or both sides of an argument after reading a text. Nevertheless, 82% of high school students graduate.

Something isn’t adding up. Either students are making up tremendous ground in high school, or we are sending half-literate adults into the world.

If schools are graduating significant numbers of young people who lack basic reading skills, it portends a serious problem for our civilization. Consider what it means to be an adult in 2025:

- Paying your bills

- Managing your budget

- Paying your taxes

- Applying for jobs

- Communicating via email

Consider what it means to take part in the political process of our Republic today:

- Voting

- Reading and understanding news stories

- Discerning the mailers and text messages during campaigns

- Understanding legislation

- Communicating with elected officials

What does it mean for our Republic when anywhere from one-third to two-thirds of adults struggle with basic comprehension?

The Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) conducted a study in 2023 gauging the general literacy of the American people. Click here to read its metrics, which I’ve summarized below:

- Below Level 1: Can handle the simplest reading tasks but not everyday documents with multiple sentences or choices.

- Level 1: Can follow simple written instructions or find obvious information, but has difficulty with complexity or ambiguity.

- Level 2: Can manage common workplace or civic reading tasks, but may struggle with dense, unfamiliar, or poorly organized material.

- Level 3: This is the level typically associated with strong functional literacy in modern society.

- Level 4: Advanced literacy — typical of highly educated readers handling complex professional or academic material.

- Level 5: Expert-level reading and analytical ability.

According to the study, more than half the population of American adults scored Level 2 or below, meaning they might read at a basic level but struggle to understand what they are reading. Another study conducted by the Barbara Bush Foundation in 2020 predicted that eradicating illiteracy—getting all adults to Level 3 in the NCES metrics—would raise America’s gross domestic product by 10%, or $2.2 trillion.

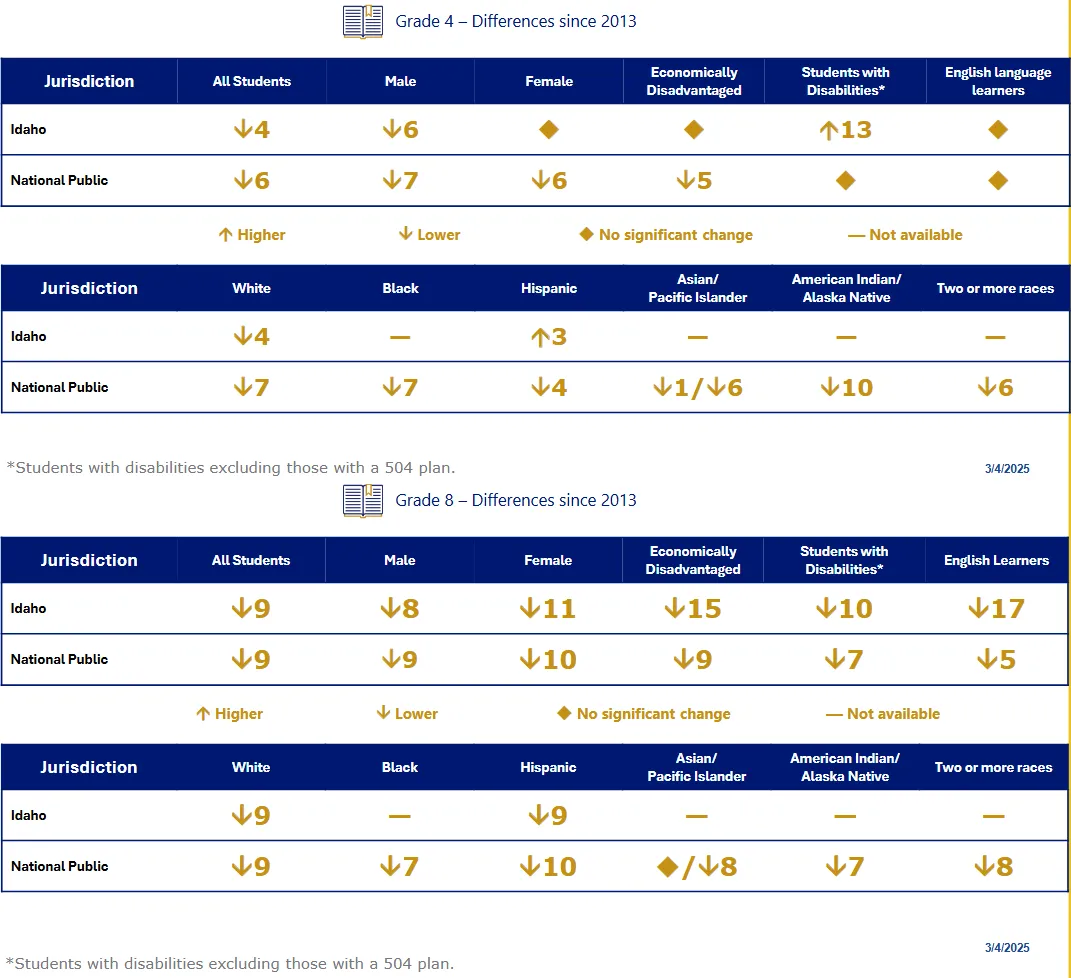

Properly assigning blame for this deficiency would take a full research team. Could demographics play a part in these low scores? The NAEP report card shows that at the 4th-grade level, scores for English language learners did not significantly change since 2013, while scores for students with disabilities went up by 13 points. Scores for boys went down six points in that span, while scores for girls remained steady. White students dropped four points, Black students remained steady, and Hispanic students rose three points.

Scores for 8th graders, on the other hand, showed a precipitous drop, with lower scores across nearly all categories.

From the perspective of government bureaucrats, there is no problem that cannot be solved with more money. To that end, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Debbie Critchfield requested additional funding from the Legislature this year to improve literacy in elementary schools. Senate Bill 1069 created a new appropriation of $5 million for the first year of a three-year program to train teachers in kindergarten through grade 3 in the science of reading. The appropriation was added via a trailer bill, Senate Bill 1213.

In his press release upon signing S1069 earlier this year, Gov. Brad Little touted $78 million in appropriations for early reading since he took office:

My priority has been and will continue to be getting all Idaho kids to read proficiently by a young age. It just makes sense. Our investments in public education later will have more impact if we can give students a strong start. It is not only our constitutional obligation but our moral obligation as well. Our five-fold increase in literacy funding since I took office is something I am truly proud of.

This, of course, begs the question: What has our public school system been doing wrong all these years that requires additional appropriations now? The answer, apparently, is that sometime in the past two or three decades, teachers and curriculum developers forgot how reading works.

S1069 provided a slight amendment to the Literacy Intervention Program, which was created as part of a comprehensive bill in 2021 that redesigned and consolidated literacy programs and standards in Idaho public education. That bill codified in state code literacy instruction based on “phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary.”

Does that language imply that there are other ways of learning reading?

I was an early reader. At age four, I was reading children’s science books, and by age six, I was reading full chapters. I completed first and second grade in a single year, almost entirely due to my advanced reading ability. My mother had taught me to read using phonics—showing me what sounds letters make and then letting me sound out the words. I did not realize until recently that this method of literacy instruction has been significantly downplayed over the past two or three decades.

I recently watched a video on literacy by author Hilary Layne, whose YouTube channel The Second Story examines literature and language:

Pause what you’re doing and watch the whole video. Layne explains in detail how “critical literacy” and whole language learning not only handicapped a generation of students, but created adults who lack the ability to think critically at all. Layne goes on to speculate that this handicapping was deliberate on the part of left-wing activists such as Paolo Freire, who believed that teaching children to read was not enough, because that only locked them into the existing system, one identified by cultural Marxists as oppressive.

Watching her video led me on a journey into the world of literacy education, a skill that I’ve taken for granted my entire life. Despite—or perhaps because of—my own experience, I never pushed my own children to read early. My wife and I read to them constantly, from birth, and have filled our home with books, but I’ve let them learn at their own pace. My three eldest started school without being proficient readers, but they each learned quickly, and now devour as many books as they can. My eldest, who is in 5th grade this year, has read the Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Harry Potter series’ multiple times through.

Unsurprisingly, their school uses a phonics-based curriculum.

A 14-episode podcast series called Sold a Story examined in-depth how phonics-based education was replaced by whole language and other teaching styles. The producer of the series, Emily Hanford, explained the problem in the first episode:

I’m Emily Hanford. I’m an education reporter. And about five years ago, I started to get really interested in why so many kids are having a hard time learning to read. And what I discovered is that in schools all over this country — and in other parts of the world too — kids are not being taught how to read.

Schools think they’re teaching kids to read. Of course they do. But it turns out there’s a big body of scientific research about reading and how kids learn to do it. This research shows there are important skills that all kids need to learn to become good readers. And in lots of schools, they aren’t being taught these skills.

Over the past few years, I produced a series of radio documentaries and articles about this. And the response was like nothing I’ve ever experienced in my career. Thousands of emails and messages and posts on social media. And there were basically two kinds of things people were saying.

The first was: I know. I know. I’ve been trying to tell people this for years.

The other response was: I had no idea. This is what I heard from lots of teachers. They had no idea they weren’t teaching kids howto read.

What I’ve been trying to figure out it is — why? Why didn’t they know? Why haven’t schools been teaching children how to read? And I have an answer.

Whole language learning began in the 1980s and 90s, embracing theories that said:

- children learn to read naturally, like learning to speak

- meaning matters more than decoding

- students should “construct” understanding from context

This led to instructional strategies like:

- guessing words from pictures

- using sentence context

- skipping unknown words and coming back later

- discouraging sounding out as “inauthentic”

I highly recommend you listen to the entire series. In the third episode, Emily Hanford explained how the already contentious world of competing educational systems became enmeshed in politics. George W. Bush campaigned for president in 2000 on a platform of increasing childhood literacy using phonics-based instruction, which caused many in the public school system to reflexively oppose it.

President Bush backed a system called Reading First as part of his landmark No Child Left Behind Act. Schools that embraced phonics instruction could qualify for additional federal funds. This angered proponents of whole language models. Hanford quoted a “liberal Democrat” teacher from the Seattle area as saying, “Forget it, I wasn’t going to do any of that. And, you know, I wasn’t necessarily rejecting the curriculum as much as I was rejecting Bush.”

I’ve seen many claims that cognitive science supports phonics instruction. Yet opponents still believe they have the moral high ground. Is it really about teaching children to read, or is it more about teaching them what to think and believe?

I recently came across a fellow on Twitter named Niels Hoven, the founder of an educational company called Mentava which uses phonics to teach preschoolers how to read. Here is how he describes his mission:

The goal of modern education policy is not “helping every kid achieve their potential”, but rather “closing the gap” between high achievers and low achievers.

Unfortunately, this means that many high-achieving students are intentionally slowed down, and held back to allow their classmates to catch up.

@MentavaInc is building software to ensure high-achieving students can have their learning needs met, starting with a software-based tutor that teaches preschoolers to read.

Remember how Hilary Layne explained that opposition to phonics-based education came partly out of the world of left-wing ideology—the Paolo Freire school of pedagogy that said it wasn’t enough to teach children to read; teachers must shape them into revolutionary activists? Niels Hoven’s method sparked an angry reaction from Dana Palubiak, whose Substack bio says she “founded MindLinked Social to explore neurodivergence, motherhood, emotional labor, and the systems shaping us. A retired teacher, she writes to name patterns, spark reflection, and help others unlearn what no longer serves.”

Her article, clearly and obviously written by ChatGPT, denounces Hoven, Mentava, and phonics-based instruction as a “case study in how tech arrogance, political grievance, and structural misogyny are being weaponized against public education with children and teachers paying the price.”

Palubiak claimed that phonics-based education is outdated and wrong:

Mentava’s premise is seductively simple:

drill phonics harder, earlier, louder, and children will magically become readers.

This isn’t innovation.

It’s pedagogical time travel.

Decades of literacy research show that reading is not sequential (“decode first, then comprehend”). It is simultaneous and integrative. The brain connects symbols to sound and meaning at the same time. Isolating decoding is like training a basketball player only to dribble, then throwing them into a game and expecting them to win.

She went on to assert that supporting phonics means opposing teachers:

Students become guinea pigs for a method science abandoned decades ago. They may learn to pronounce words without understanding them becoming “word callers,” frustrated and disconnected from reading.

Teachers become targets. Our professional feedback is recast as emotional hysteria. Harassment campaigns are launched to silence us. Our labor is degraded in public, again and again.

And public trust in education erodes.

Palubiak also said that since most public teachers are women, disagreeing with modern pedagogy is also deliberate and structural misogyny.

Twitter anon memetic_sisyphus interpreted the hit piece:

It’s been the modus operandi for years but this is an excellent case of it. Teachers organizations are extremely sensitive to any threat to their perception as the only force capable of educating students.

Can you see the pattern here? Teachers’ unions and pedagogical associations claim sole authority over education, even to the extent of claiming children as their own, over and above parents. These same figures and organizations fight tooth and nail against alternatives to their control, from charter schools in decades past to school choice options today. Despite scores such as the NAEP showing that fewer than one-third of students are proficient readers, they cling to their systems and call critics misogynistic and stupid.

Niels Hoven suggested that the problem is that the education establishment is more concerned with reducing the gap between high and low achievers rather than raising achievement across the board:

Public schools are 100% capable of supporting the outlier outcomes that Alpha School trumpets.

(My public school did, when I was kid)

The formula is straightforward:

If a kid can learn fast, let them learn fast

Schools can do this in groups (by grouping kids of similar ability)

Or individually (with quality educational software)

But instead, anti-excellence policymakers have decided that our schools’ top priority should be equalization, not education.

Decades of “critical literacy” and whole language education, as Hilary Layne put it, created a system in which students not only struggle to read, but those that can are unable to substantively understand what they are reading.

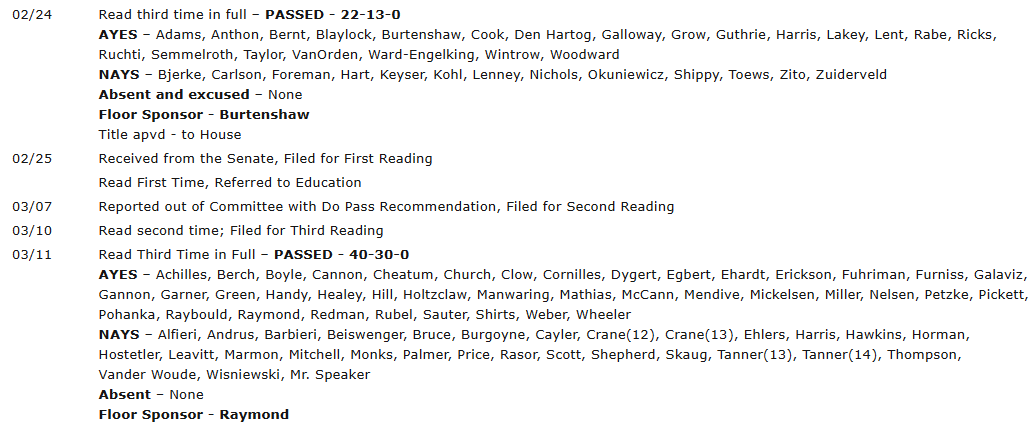

Education leaders in Idaho must have recognized that there was a fundamental problem with literacy in our state. 2021’s Senate Bill 1006, the comprehensive rewrite of laws related to literacy in the public school system I mentioned earlier, was an attempt to correct our course, codifying phonics-based instruction. 2025’s S1069 added more money while sharpening execution. Interestingly, despite S1006 passing the Legislature unanimously in 2021, S1069 barely squeaked by this year. Conservatives in both the House and the Senate voted against the bill, arguing it was sending good money after bad.

Floor sponsor Rep. Jerald Raymond explained that there were still gaps in literacy since 2021, requiring the additional appropriation, and called S1069 the most important bill the Legislature would consider that year. Rep. Kyle Harris, however, expressed his skepticism that the $5 million one-year appropriation would go directly toward literacy and would instead diffuse into the bureaucracy.

In the same session, Harris sponsored a bill requiring schools to properly account for all appropriations. That bill passed the House but was not given a hearing in the Senate.

Rep. Vito Barbieri said he remained astounded at how much money Idaho pours into public education, even as test scores don’t go up. “How can money be the answer?” Reps. Kent Marmon and Faye Thompson agreed.

Rep. Lori McCann pushed back, lamenting what she called the negativity toward public education, saying the Legislature was setting teachers up for failure rather than giving them the tools to fix the problem. Rep. Rick Cheatum debated in favor of the bill, saying that reading had changed, and Rep. Mark Sauter said the Legislature should support continuous improvement for teachers.

Rep. Dan Garner, also debating in support of the bill, pointed out the elephant in the room: Idaho had moved away from phonics as the primary method of teaching reading. He said the teachers who used the new program passed in 2021 had seen improvements in student literacy and said the new appropriation was necessary to teach teachers how to teach phonics.

Democratic Rep. Soñia Galaviz, herself a schoolteacher, explained that current conventional wisdom in literacy education involved a holistic approach. Nevertheless, the actual “cracking the code” of reading was phonics-based. “We have gotten away from some of that direct, back-to-basics, attack-the-code, learn the parts of a word and master reading early on.” She called the bill a “worthy investment” in children’s lives.

Debate lasted for more than half an hour before the bill passed 40-30.

From my perspective today, having read and researched this subject, I see both sides of the debate. I agree with those who opposed the bill that the public school system is already flush with cash—more than $3 billion in tax dollars—so why should we appropriate even more? Sam Lair, director of the Center for American Education at the Idaho Freedom Foundation (IFF), analyzed the bill, scoring it -1 on IFF’s Freedom Index:

Since 2017 the cost of the literacy intervention program has increased from $9.1 million a year to $72.8 million a year for a total investment of $257,737,100 over seven years. Despite the financial investment put into the literacy intervention program, no significant correlating growth in reading proficiency has been observed. From 2017 to 2024, the percentage of fourth grade students scoring proficient or above in English and language arts on the ISAT has only increased from 48.0% to 49.4%. All the while, the most recent performance reviews for Idaho’s public schools deemed 98.4% of teachers “proficient” or better. It is clear from this data that there is a failure of accountability in Idaho’s system of public education that will not be fixed by investing more in teachers with a track record of poor student performance. For this reason, additional funding for the literacy intervention program cannot be justified.

On the other hand, I find myself in agreement with Reps. Garner and Galaviz that the public school system needs to correct its course and return to phonics-based education. That’s exactly what people like Hilary Layne and Niels Hoven are talking about.

Yet I have questions:

- Does it really require another $5 million investment per year in public education to fix the problem?

- How much does it cost to teach a child to read?

- Are teacher training programs and curriculum developers still avoiding phonics?

- If test scores remain low in the future, will education leaders simply ask for more money?

- How do we, the taxpayers and citizens of Idaho, measure success?

With regards to literacy, low test scores are the least of my concerns. An adult population that struggles with comprehension is not only unable to meaningfully take part in the public square but is easily misled, whether by political candidates and organizations or by scoundrels who take advantage of people’s ignorance.

Yet the pace of modern technology seems to be creating new opportunities to avoid literacy, as smartphones and artificial intelligence provide a way for people to outsource their own thoughts to machines. Who needs to learn to read complex texts when ChatGPT will read and summarize them for you? Who needs to learn to write properly if Grok or Claude will do it for you, as Dana Palubiak demonstrated?

We’re entering an uncertain future, one that might well see a bifurcation of society like something out of H.G. Wells’ dystopian imagination. Those who are literate, who can make sense of the world, will have the opportunity to flourish, while those who struggle—the children who are left behind—will be at the mercy of their increasingly intelligent gadgets.

What can society do to ensure every American child can not only read but properly comprehend the world around them? Is there a solution in the government school system, or will it be easier to accomplish with more variety, more school choice, more alternatives? Niels Hoven’s Mentava program is pricey—$500 per month—yet that’s a bargain compared to the $9,000–$13,000 our state spends each year on average for each student enrolled in the public school system.

Having sifted through all of this information, I have a new appreciation for what our public school leaders and legislators are trying to do. Universal literacy is a noble goal. However, I suspect that real solutions are going to come from outside the government system. Just like President Bush’s efforts to implement phonics 25 years ago, such solutions will run into a lot of institutional opposition. After all, it was the public school system that went away from phonics in the first place, whether out of a sincere belief that it didn’t work, or as cynical political opposition.

It’s time to stop worrying so much about the achievement gap and instead allow all children to learn at their own pace. It’s time to think outside the box and embrace new solutions that let every child flourish in their own way, rather than maintaining a one-size-fits-all system. It’s also time to consider bold ideas while returning to time-tested methods, such as phonics, which were abandoned by pedagogical theorists who thought they knew better. Only then can we truly say we are leaving no child behind.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.