Nobody likes taxes. Yet most people like the things taxes pay for. As conservatives, we believe in some government—limited government, good government—but not no government. The same rules that apply in the private sector apply here too: quality costs more than cheap. And as Christians, we believe the aphorism that a workman is worthy of his wages, even if that workman is in the public sector.

All that said, of course we want to keep taxes as low as possible across the board. Yet not all taxes are equal. Some are structured to impact certain classes of people more than others. Some fund local services, while others are used statewide. The first step in changing something is understanding it, so I’d like to offer this primer on Idaho taxes. (Let’s leave federal taxes out for now—they’re far harder for any of us to change.)

I most recently wrote about this last July, looking at Idaho’s so-called “three-legged stool” of taxation: income tax, sales tax, and property tax. I won’t rehash that article; go back and read it for background. Today I want to focus on what we get in return for the taxes we pay.

The impetus for this piece was an article by highly respected columnist Scott Greer on property taxes. Greer often takes positions that run counter to conventional wisdom on the right, and in doing so adds missing components to the conversation. Property taxes, for many conservatives, are a bete noire. I’ve shared my own concerns over the past few years:

- The Truth About Property Taxes

- The End of Property Taxes?

- Are Taxes Immoral?

- Idahoans Vote for More Property Taxes

- Can We Eliminate Property Taxes in Idaho?

Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida has suggested eliminating property taxes entirely, and former State Senator Scott Herndon has made eliminating them a centerpiece of his campaign.

However, Greer suggests that property taxes may be the most conservative tax there is, because they fund local government. Rather than going to a distant capital to be redistributed according to the whims of nameless bureaucrats or elected officials, property taxes support your community: cities, schools, roads, police, firefighters, and more.

Many Americans view their house as their own self-contained castle. They fail to see the roads that lead to their house and the first responders who protect it as an obligation they need to support. All of this is just supposed to magically exist on its own regardless if you pay your property taxes.

Take the time to read Greer’s article and consider his arguments. Personally, I’m still pondering them. I dislike how property taxes are levied on unrealized gains: if you buy a home for $100,000 in 2000 and it’s worth $1.2 million in 2025, you’re paying taxes on the latter figure, not the former. Yet most proposals to adjust this open their own cans of worms. If we were to replace property taxes with a state-level sales tax, for instance, what would happen to local accountability?

It’s a complex subject.

Marta Mossburg of Mountain States Policy Center (MSPC) recently wrote about property tax reform in Wyoming, echoing some of the same ideas as Greer:

As for a region’s economic outlook, multiple studies show that property taxes are healthier for growth than income and sales taxes. The data is clear: property taxes are both the most efficient way to raise local revenue, do the least harm, and can even help increase gross state and domestic product when taxes are shifted from income and sales taxes to property taxes.

Property taxes fund local services—most of which, like roads, we all use, while others, like police and fire protection, we hope never to need. Looking at my own tax bill, my property taxes pay for the City of Eagle, Ada County, West Ada School District, Ada County Highway District, Eagle Fire District, Eagle Sewer, Ada County mosquito abatement, and the College of Western Idaho. Your own bill will vary.

I wrote last June about “government as a service” suggesting that property tax dollars are like subscriptions—somewhat like Netflix or Amazon Prime. Unlike Netflix or Amazon, however, government services are not optional. This is where many conservatives and libertarians have a problem: our resources are taken against our will to pay for things we don’t necessarily support. Hence the phrase, “taxation is theft.”

Still, taxation has been part of human society since its earliest days. As soon as people began congregating in cities, they realized the need for a system to support the common good. Of course, it was all too easy for tyrants to abuse this power for personal gain—just look at King John in the Robin Hood stories.

The English principle of “no taxation without representation”—under which the king could not impose taxes without Parliament’s consent—was not the natural state of civilization, but a revolutionary step in civil rights. In 1215, Magna Carta, which King John was forced to sign, declared plainly:

No scutage or aid may be levied in our kingdom without its general consent…

Even today, elected bodies from cemetery boards to the Legislature cannot increase taxes without a vote from the people’s representatives. Article VII of the Idaho Constitution explains that the Legislature has the power to tax, and that authority is delegated to local elected bodies. Ideally, legislators and taxing district directors alike would listen to input from their constituents regarding tax proposals and vote accordingly. Voters always have the option of replacing elected officials who act without their consent.

At an even lower level of governance, homeowners’ associations (HOAs) levy dues on citizens. Many people rightly take issue with HOAs: in some neighborhoods, owners cannot do anything without board approval, making the very concept of ownership seem farcical. A good HOA, however, exercises the lightest regulatory touch while using member dues to maintain common areas. HOAs are technically optional—you must agree to their covenants, conditions, and restrictions (CC&Rs) when buying your home.

Living in any taxing district is, in theory, optional. Someone moving to Idaho can choose low-tax Eagle, high-tax Boise, or a remote area with far fewer services. Yet in practice, choices are constrained by work, family, schools, and even geography or climate. Generally, the more municipal services that are available, the higher your property tax rate will be.

As Thomas Sowell said, there are no solutions, only tradeoffs, and the tradeoff for fewer taxes means you might have to pay to run electricity to your homestead, dig your own well, install your own septic tank, and have much longer response times for police, fire, and emergency medical care. That is a choice that some people make, and more power to them.

Generally, however, wherever we live, we must pay taxes. So where do they go?

Property taxes primarily fund local services. Local public schools rely on them, as do firefighters and emergency medical personnel. Sheriff’s offices and police departments need property taxes to pay for staff, equipment, and jail facilities. Almost every local service depends, at least in part, on property taxes.

When you pay your property tax bill, it goes to your county treasurer, who then distributes it according to the levy rates to each taxing district. Property tax money does not flow through the Capitol.

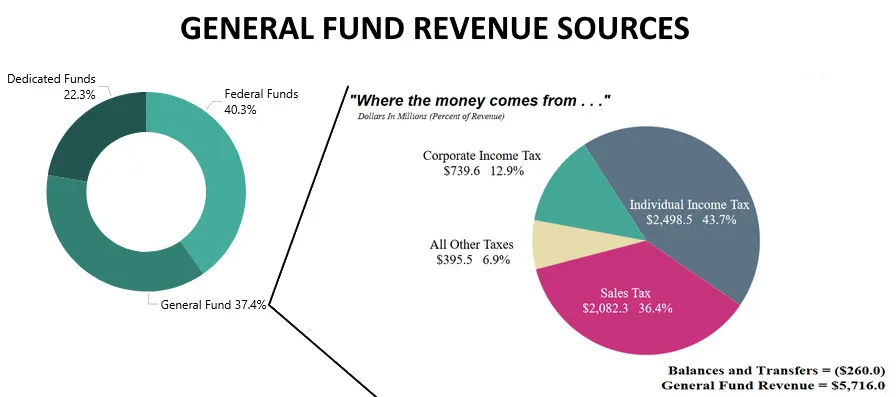

State government is funded by income and sales taxes. Idaho’s personal income tax is a flat 5.3% for anyone earning more than $2,500. For example, a $100,000 income results in slightly more than $5,000 going to the State of Idaho (not counting federal taxes). Corporations also pay 5.3% on profits.

Those funds flow into the state’s General Fund, distributed to agencies according to the Legislature’s annual budget. Income taxes support state government, state police, transportation projects, public schools—especially staff salaries—and welfare programs such as Medicaid.

The 6% sales tax also goes into the General Fund, though portions are diverted to cities and counties through revenue sharing and to school facilities funds via recent property tax relief legislation. That means sales taxes support both statewide initiatives and local governments—not necessarily your hometown or the place of purchase. Distribution is complex, generally based on population and property values. For example, a $10 lunch at McDonald’s incurs $0.60 in sales tax. That sixty cents is then split—some to multiple cities, some to schools, and the remainder to the General Fund.

Other taxes and fees, such as hunting licenses or gas taxes, go into the Dedicated Fund, which finances specific items like wildlife management and highway maintenance.

Each tax has advantages and disadvantages, both in the manner in which they are collected and what they fund.

Property taxes are levied on ownership rather than transactions, which can burden retirees who have paid off their homes. Programs like the homeowner’s exemption and the circuit breaker program help ease that burden. Still, the idea of continually paying a levy simply for owning something feels inherently wrong to many of us, despite its long history in America. Yet property taxes fund essential local services—and, as Scott Greer noted, conservatives generally believe government should be as close to the people as possible.

Is there a way to fund local services and retain local control without relying on a tax on property?

Renters pay property taxes indirectly, since landlords typically factor those costs into monthly rent. Many homeowners with mortgages also lose sight of what they pay, because banks often bundle taxes and insurance into escrow accounts. I prefer to keep them separate and pay directly, because I want to know exactly where my money goes.

Income taxes make working or doing business more expensive, potentially discouraging high earners or companies from moving to Idaho. Still, they are often seen as fairer than other taxes, since those with higher earnings pay more, and they provide predictable revenue for budgeting.

Avery Nichols, who participated in MSPC’s Sawtooth Leadership Academy, recently won a scholarship for his paper advocating for the complete abolition of income taxes in Idaho. He laid out options for replacing that lost revenue, such as increasing sales taxes or implementing novel ideas like a mineral extraction tax.

Sales taxes increase the cost of every purchase you make. Much hay has been raised over the fact that Idaho is among the handful of states that tax groceries. Originally, the tax was meant to provide a broader revenue base, particularly for education. Many conservatives consider consumption taxes the most fair, since citizens can directly choose how much to pay.

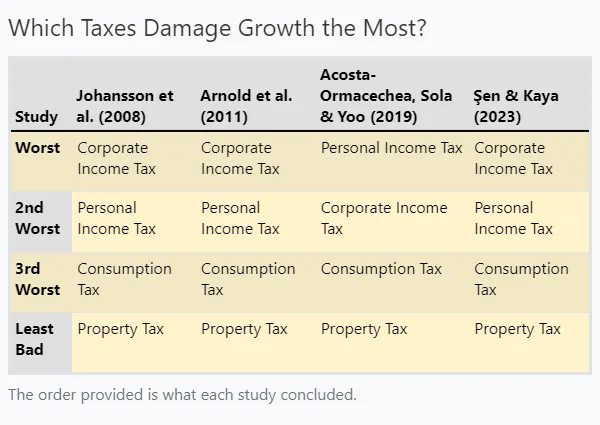

Several studies collected by Twitter poster Crémieux concluded that property taxes least hamper growth, while income taxes are the most damaging:

Idaho political leaders have varied priorities. My own state senator Scott Grow, chair of the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee (JFAC), dislikes property taxes and is constantly trying to give relief to homeowners. Speaker Mike Moyle, on the other hand, hates income taxes, working to reduce personal and corporate rates each year.

Personally, I’m fine with lawmakers battling each other over how many taxes to reduce. Everyone wins in that kind of fight.

Some city and county personnel, however, are unhappy with Speaker Moyle after he pushed legislation to cap annual property tax increases. They argue this limits their ability to fund services demanded by residents or mandated by the Legislature.

I appreciate that lawmakers passed so much tax relief in the 2025 session: reduced income tax rates, increased grocery tax credits, and more property tax relief. With a looming budget shortfall, additional relief next year is probably impossible. On the other hand, raising taxes in an election year would be political suicide, which means—as Fred Birnbaum of IFF wrote this week—cutting spending is the only viable option in the upcoming legislative session.

Having digested all of that, what do you think about Idaho’s three major taxes? Should we keep the “three-legged stool” in balance, or cut off one of those legs entirely? Should we eliminate property taxes, as Scott Herndon and Gov. Ron DeSantis propose? Should we eliminate the income tax, as Avery Nichols suggested? Or should we abolish sales taxes instead?

We all want lower taxes and more responsible spending. But as we decide where to focus our limited time and energy, we have to prioritize. Having taxes managed by representatives elected by the people is, in itself, an extraordinary privilege, a chance to participate directly in the work of republican government. It’s not something we should take for granted. Let’s learn all we can about the taxes we pay and work with our elected officials to keep them as low and as fair as possible.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.