There’s a scene in the 1970 film Patton where the title character walks among the ruins of ancient Carthage and declares that he is the reincarnation of ancient warriors:

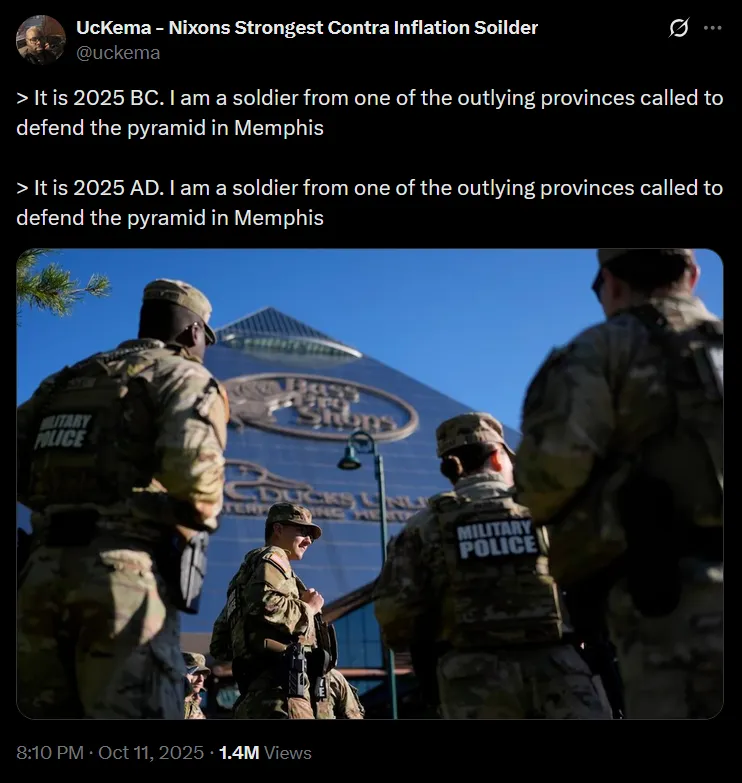

As a Christian, I don’t believe in literal reincarnation (“…it is appointed for man to die once…” — Hebrews 9:27). However, there is clearly a certain warrior archetype that appears in every generation and every society. Or, as a random Twitter poster put it in a viral tweet last night:

There have always been many reasons for men to go to war. Some went to defend their homes and families. Others went for pay or for glory. Still others were conscripted against their will. Yet all who served share a certain bond that those on the outside can never truly understand. As someone who never served in the military nor saw combat in my life, I can only learn about their experiences second- or third-hand.

All wars are bloody and terrible, some more than others. World War I demonstrated what happens when the military complex embraces the Industrial Revolution—destruction on an apocalyptic scale. In just 140 days on the Somme, Great Britain lost more soldiers than in all its wars from Waterloo to the eve of the Great War. Many WWI combat deaths were not at close range either—men were mowed down by machine guns in the no man’s land between trenches, or obliterated by artillery shells fired from miles away. Still more were felled by gas attacks or disease.

The Great War produced two fascinating works of literature, both by German combat veterans. Erich Maria Remarque was conscripted into the Imperial German Army at the age of eighteen and spent six weeks on the Western Front before being wounded by shrapnel. He published All Quiet on the Western Front ten years later, offering a brutal look at the realities of war. Remarque puts the reader in the shoes of a young German like himself, whose head is filled by parents and teachers with notions of the glory of war. Yet his experience is nothing like the stories. He watches his friends die in agony, trapped in no man’s land—close enough to hear their cries, yet too far to help. The main character, Paul (Remarque’s original middle name), is shot mere hours before the armistice of November 11, 1918.

Ernst Jünger served on the Western Front as well, for nearly all four years of the war. Wounded seven times, Jünger continually volunteered to return to the front, eager for more action. His postwar memoir, Storm of Steel, described how war brought out the best of human nature—honor, self-sacrifice, and loyalty.

As someone whose combat experience is restricted to childhood schoolyard scuffles, I can only read stories like these from a distance and conclude that war is all of these things and more. General William T. Sherman—whose unmerciful campaign of total war made him a hero in the North and a devil in the South—said, “War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it.” His opponent in the Civil War, General Robert E. Lee, remarked, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”

Yet many of the best people in our history were forged by war and combat. Would George Washington have been such a great leader and president without his battlefield experience? Harry Truman’s time on the front lines of World War I surely helped him understand the magnitude of dropping the first atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. John Kennedy and George H.W. Bush both served in combat during World War II, despite their wealthy fathers, and both faced death in the Pacific before returning home to enter politics. How could that experience not shape the leaders they became?

For generations, Republicans have held military service in high honor, with many believing it to be a prerequisite for high office. Yet it’s been more than two decades since America elected a president with military service—and even then it was George W. Bush’s tenure in the Texas Air National Guard, insulated from combat. The last three presidential contests have been between candidates with zero military service at all.

Perhaps this reflects the Pax Americana, or a shift away from military service among the scions of wealthy and powerful families. The last such gap in presidential service stretched from the election of William Howard Taft in 1908 to the succession of Harry Truman in 1945, a period when veterans of the Civil War had aged out and those of World War I and II had yet to come of age.

That pattern is surely ending as veterans of the Global War on Terror take the baton reluctantly handed off by the Baby Boomers. Republican leaders like Vice President J.D. Vance and Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida served in the Marine Corps and Navy, respectively, though neither saw front line combat. Many other young veterans are waiting in the wings as well.

The War on Terror was unlike any war our society has ever experienced, yet in many ways it was the same story replayed since the dawn of time. We don’t yet have as much literature or film that brings the war home to civilians like me, as we do from Vietnam or World War II. Yet the veterans are telling their stories.

I recently finished The Glass Factory, a memoir by Idaho’s own Braxton McCoy. (He lived most of his life in Utah, but he’s here now, so I’m claiming him.) His website describes the moment that changed his life forever:

In 2006, Sgt. Braxton McCoy (Ret.) while performing a security detail outside of Ramadi, Iraq, was severely wounded by a suicide bomber. Both his legs and arms were broken in multiple places, spine was fractured, had a number of fractured ribs, had bleeding on the brain, and a severed medial nerve to his right hand. What followed was over two dozen surgeries and nearly a decade of physical therapy and rehabilitation.

The Glass Factory is not only the story of Braxton’s physical recovery, but also of his mental and spiritual ordeals. Between PTSD, a traumatic brain injury, and many months of opioid use for pain management, McCoy faced incredible challenges. He was told he would never walk again, but he overcame that prophecy and went on not only to walk, but to run, hike, and even climb mountains.

I finally had the pleasure of meeting Braxton a few months ago when he and his colleagues at the Sagebrush Institute hosted a talk with Sen. Ben Adams about managing public lands in Idaho. If I didn’t already know his story, I would not have guessed what he had endured since his time in Ramadi.

The book is well worth your time. Buy an autographed copy here.

As I read his story, I gained a glimmer of understanding of how the warrior spirit remains a part of human society. Braxton McCoy is just the latest incarnation of that archetype—one that reaches back into the mists of prehistory. The experience of war and combat forges a bond unique to those who live it, no matter the generation. Technology has changed; geopolitics have changed; but human nature never changes. The Roman legionary fighting in Gaul, the English longbowman at Agincourt, the Confederate soldier at Petersburg, the U.S. Marine at Iwo Jima, and the American GI at Ramadi are bound together by the common thread of experience.

William Shakespeare understood human nature. In Henry V, retelling events that occurred nearly two centuries before his own time, the Bard has his title character disguise himself as a common soldier and walk among the camp to gauge morale on the eve of Agincourt. Some soldiers are frightened, some are determined, and most simply want to do their jobs and return home. King Henry feels the weight of responsibility, asking himself whether his cause is just enough to risk the lives of his men.

A modern filmmaker could easily adapt this scene to a modern war with few changes to the dialogue. The next scene features perhaps the greatest pre-battle rallying cry in history: the famous St. Crispin’s Day speech.

Early in The Glass Factory, Braxton McCoy notes how his and his comrades’ experience was shaped by the pop culture they consumed before deployment. Soldiers today likely grew up playing Call of Duty and watching movies like Saving Private Ryan and Full Metal Jacket. Is that so different from young Roman legionaries retelling The Aeneid before marching to battle, or Greek spearmen listening to recitations of The Iliad?

Indeed, Saving Private Ryan has a scene in which a young and inexperienced soldier, brought along for his ability to speak German, remarks that they are just like the men of the Light Brigade, immortalized in Tennyson’s poem. His comrades ridicule his naivete, and by the end of the movie, Corporal Upham has learned that war is much more visceral than poems and stories.

Tennyson wrote “The Charge of the Light Brigade” to honor the courage of British cavalrymen at Balaclava during the Crimean War. A generation later, Rudyard Kipling wrote a scathing response, castigating the British people for enjoying the glory of their veterans’ sacrifice yet forgetting them once they returned home.

Societies throughout history have struggled with how to deal with combat veterans. We teach men to kill, then expect them to reintegrate into civilian life once our need for that skill has passed. Honoring the dead is simple; honoring the survivors is harder. After World War I, Laurence Binyon wrote a poem called “For the Fallen,” which contains these lines:

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted;

They fell with their faces to the foe.They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Filmmaker Peter Jackson used a line from that poem as the title for his revolutionary documentary about World War I soldiers, which used modern technology to add color and dialogue to original footage. The film ends with surviving soldiers returning home, only to find themselves out of place there.

J.R.R. Tolkien understood. A veteran of the Somme, he drew from that experience in writing The Lord of the Rings. Many assumed the books were allegories for World War II, with the One Ring representing atomic bombs or modern technology. But they are, in truth, Great War stories. Four friends embark on a journey into foreign lands, hoping to save their beloved home, and find themselves in the middle of a war. Frodo and Sam’s journey through Mordor—with its pits, ash, and noxious fumes—was surely inspired by Tolkien’s time in the trenches of the Western Front.

In the end, Frodo saves the Shire, but at the cost of himself. He returns home with permanent wounds: not only a missing finger and the lingering pain of the spider’s bite and Morgul blade, but deeper mental and spiritual scars. Unable to live in the world he saved, he departs for the Undying West, the only place where he can find peace.

Real life is not a movie, and there is no Valinor to which our veterans can depart. As Braxton McCoy’s experience shows, real healing takes years, or even decades, and for many, the scars will never fully fade. It’s up to those of us who did not serve to do whatever is necessary to make such healing possible.

War never changes, no matter the technology or geopolitical situation. While combat can bring out heroic qualities in men, it is still, as General Sherman noted, a cruel hell on earth that we should avoid whenever possible. “War is policy by other means,” wrote Carl von Clausewitz, which means we should exhaust every political and diplomatic option before sending our young men and women into battle. We honor the troops not only by caring for them when they return home, but by ensuring that their cause—as Shakespeare’s King Henry understood—is just.

As someone who never served, I hold in the highest esteem those who did. No matter our politics, I thank you for your service, and I hope that we as a society have upheld our part of the bargain that began when you put on the uniform.

Feature image from the United States Army.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.