Perhaps the most important maxim to remember when engaging in political discourse is King Solomon’s observation that “there is nothing new under the sun.” Technology advances, but human nature remains unchanged, which means we keep debating the same ideas in new contexts.

I’ve noticed a temptation among conservatives to believe that social problems and dangerous ideologies are recent inventions. Most of us tend to look back on a nostalgic past—Boomers see the 1950s as idyllic, while my generation recalls the mid-1990s with fondness. The corollary to that nostalgia is the belief that “wrong” ideas like socialism are recent arrivals in the marketplace of ideas.

I was reminded of this again while reading about the debates surrounding the New Deal in the 1930s. Many American intellectuals believed free-market capitalism had reached its breaking point and that some form of socialism was inevitable. The old monarchies of Europe, shattered by the Great War, were being replaced with seemingly new ideological and economic systems. Russia exchanged the czar for Bolshevik Communists Vladimir Lenin and Josef Stalin. Italy embraced Fascism under Benito Mussolini. Germany’s brief experiment as a republic ended with Adolf Hitler and his National Socialists.

Leading American intellectuals did not view these revolutions as a bad thing. Many admired Stalin, Mussolini, and even Hitler—not as merciless dictators but as leaders advancing the cause of humanity. Mussolini and Hitler rightly fell into disrepute after World War II—it is hard to find anyone defending Hitler today outside of dark corners of the internet—but Stalin is still praised by supposedly mainstream academics, despite having a larger body count than the other two combined.

In fact, many Americans—including folk singer Pete Seeger, author Ernest Hemingway, poet Langston Hughes, and hundreds of other artists, authors, and professors—signed a letter defending Stalin and calling for “unity of the anti-fascist forces” against Hitler, Mussolini, and Francisco Franco of Spain. Yet mere days after its publication, Germany and the Soviet Union announced a non-aggression pact and jointly invaded Poland. Suddenly, these communist sympathizers called for peace with Germany. Two years later, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, they changed their tune again—and this time the U.S. government joined the cause, providing Stalin the means to defend against Nazi aggression.

Socialism was fashionable in America during the 1930s and 40s, and Idaho was no exception. In 1944, only months after the D-Day landings in Normandy, the Gem State elected outspoken socialist Glen Taylor to the U.S. Senate. Early in his term, Taylor submitted a resolution calling for the creation of a world republic. He generally supported the progressive domestic policies of President Harry Truman but broke with him on Cold War measures such as the Marshall Plan, believing it was too antagonistic.

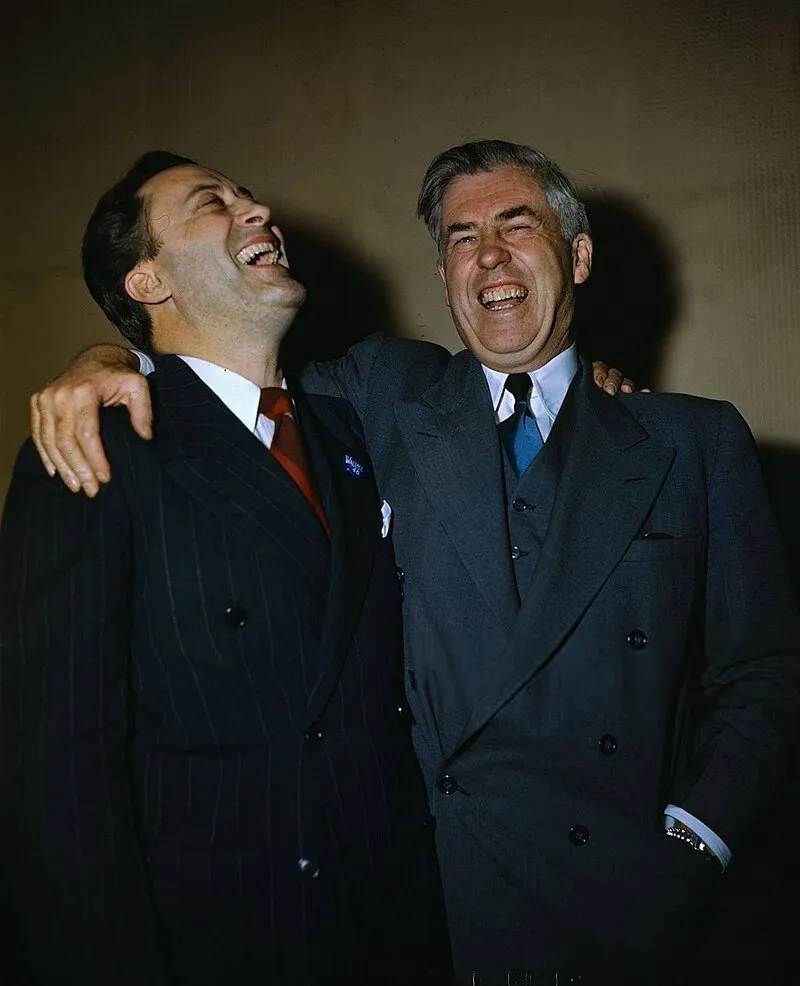

In 1948, Taylor was nominated for vice president by the new Progressive Party, which put former Vice President Henry Wallace at the top of the ticket. Wallace is a fascinating historical figure—his ideas were incredibly destructive, yet cloaked in a banality that made him seem far less dangerous than a Hitler or Stalin.

In 1942, while still vice president, Wallace gave his most famous speech, calling the 20th century “The Century of the Common Man.” He drew a line from the American Revolution to the Russian Revolution, casting the current fight against the Nazis as the culmination of a long uprising of regular people against powerful interests. His words inspired Aaron Copland’s famous Fanfare for the Common Man.

According to Michael Malice in The White Pill, Wallace even visited Soviet gulags in Siberia and returned praising the prisoners’ “pioneering spirit,” comparing them to American frontiersmen. He denied the mass torture and starvation that was already well documented, excusing Stalin’s deliberate genocide of Ukrainians known as the Holodomor. To his credit, Wallace eventually recanted, admitting Stalin was a monster. Still, he was hardly alone in his earlier admiration. Democratic Party insiders were so worried about the potential of a socialist-friendly president that they forced Wallace off the ticket in 1944 in favor of Truman.

The Wallace/Taylor ticket was crushed in 1948, taking fourth place behind Truman, Thomas Dewey, and Strom Thurmond, running on a platform of segregation. Around this time, the House Un-American Activities Committee began investigating Soviet-directed communist influence in government and culture, while Sen. Joseph McCarthy accused the Truman administration of harboring communist sympathizers.

As for Sen. Taylor, his quixotic vice presidential bid cemented his status as a one-termer, and he lost his 1950 primary. Idaho would go on to elect Democrat Frank Church in 1956 and vote for Lyndon Johnson in 1964—the last time our state turned blue on the presidential map.

Yet ideological lines between conservatives and progressives were still blurry. Robert Smylie, the first Idaho governor born in the 20th century, was elected in 1954. He promptly pushed a bill abolishing gubernatorial term limits, succeeded, and went on to serve three terms. Smylie opposed right-to-work laws and introduced the state sales tax. His policies were not radically different from Cecil Andrus, who later served nonconsecutive terms as Idaho’s most recent Democratic governor.

Despite not going down the road of Fascism, Nazism, or Marxism-Leninism, America was nevertheless transformed during the 1930s and 40s. Citizens increasingly demanded government services and a social safety net. When Franklin Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act in 1935, he ensured it was funded by payroll taxes so that workers would feel they had paid into the system, making repeal politically impossible:

We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program.

As Ronald Reagan later quipped, the closest thing to eternal life on earth is a government program. Roosevelt discovered the secret of political patronage: make people dependent, and you’ll never lack for votes. Sen. Robert Taft—“Mr. Republican”—wanted the New Deal dismantled, but Roosevelt never won fewer than 430 electoral votes. His programs were broadly popular, regardless of constitutionality or efficacy.

That is the conservative conundrum: we may be right on principle, but restricting government is always a harder sell than promising voters free benefits at taxpayer expense. Consider Gov. Brad Little’s 2023 Launch Grant—a leftist-style free college program that funnels tax dollars to politically connected businesses using students as bagmen. He touts its popularity by quoting happy students, but as the old saying goes, if you rob Peter to pay Paul, you can always count on Paul’s support.

Dwight Eisenhower, the first Republican president after the New Deal, recognized this dilemma:

Now it is true that I believe this country is following a dangerous trend when it permits too great a degree of centralization of governmental functions. I oppose this–in some instances the fight is a rather desperate one. But to attain any success it is quite clear that the Federal government cannot avoid or escape responsibilities which the mass of the people firmly believe should be undertaken by it. The political processes of our country are such that if a rule of reason is not applied in this effort, we will lose everything–even to a possible and drastic change in the Constitution. This is what I mean by my constant insistence upon “moderation” in government. Should any political party attempt to abolish social security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group, of course, that believes you can do these things.

What does this mean today? The communist sympathizers lost the great debate of the 20th century—Stalin’s Soviet Union murdered millions yet ultimately collapsed under its own weight by 1991. But there are always technocrats who are convinced that representative democracy and the free market simply don’t work in the 21st. Politicians are always tempted to “do something,” because, as FDR proved in his four election victories, voters reward action—even failed action—over restraint.

We must remember that the idea of socialism has been around for centuries, long before Karl Marx gave it a name. Consider the Diggers, a faction of Englishmen in the mid-1600s who sought to abolish private property. Even American populists leaned toward socialism at times—for example, the People’s Party of the 1890s, which called for abolishing private banks, subsidizing farmers, imposing a progressive income tax, and nationalizing railroads. In 1892, Idaho’s first presidential election following statehood, our electoral votes went to the People’s Party candidate James Weaver.

Conservatives must rally around a positive vision of the future that is neither fully anarcho-libertarian nor the quasi-socialism that has been America’s norm since the New Deal. We must promote a free market that serves the American people—cutting off taxpayer subsidies for big corporations while easing burdensome regulations. We must abandon the notion that government exists to give established businesses a competitive edge, as with the racket of certification and licensure. And we must begin rolling back the welfare state, starting with repealing Medicaid expansion for able-bodied working-age adults.

Expanding government can bring short-term benefits, while reining it in often brings short-term pain. Politicians, facing re-election every two, four, or six years, are incentivized to chase immediate payoffs. Our task is to elevate statesmen who think in terms of the next twenty, forty, or sixty years instead. That requires steady, determined work—but also readiness to strike while the iron is hot. FDR transformed America more in his first hundred days than it had changed in the previous fifty years. In the same way, President Donald Trump’s administration is moving us back in the right direction. Now it falls to us in Idaho to resist the creeping growth of government and keep our state the freest in the nation, while we still have the chance.

Conservatives always face the uphill task of convincing voters that leaving people alone is often the best course. As John Kennedy said, we do the things we do “not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” Removing the yoke of government from the necks of our children and grandchildren is a noble cause, one worth our finite time and energy.

There is nothing new under the sun. As Ronald Reagan reminded us, freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction—each generation must fight anew against the old human temptation of control.

Feature image: Henry Wallace as editor of New Republic | Des Moines Register file photo

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.