Last week, I wrote about the state of property taxes in Idaho and what it would take to eliminate them. Readers responded with a lot of feedback that I’d like to share with you today.

Several readers suggested that retirees should be exempt from property taxes. I’m sympathetic to this view. It’s troubling that people who’ve long since paid off their mortgages must continue paying an annual fee to the government just for the privilege of living in their own homes. Retirees have been paying into society all their lives, and at this point, they aren’t the ones using public schools, parks, and other services.

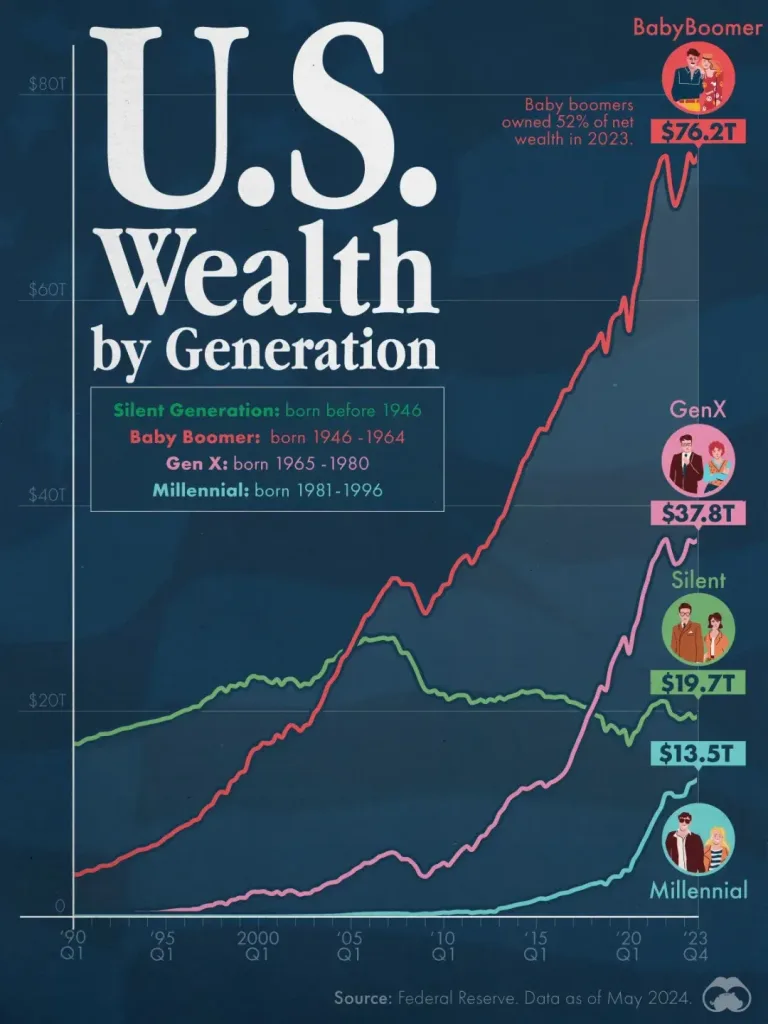

On the other hand, exempting one group from property taxes doesn’t reduce the overall tax burden; it merely shifts it onto everyone else. The homeowner’s exemption, for example, shifts a greater share of the tax burden onto businesses and those with multiple homes. Exempting senior citizens would shift the burden onto younger generations, who already have far less wealth per capita than retirees.

Recall that the biggest problem with Obamacare was the way individuals were mandated by the government to purchase health insurance, even if they believed they were healthy enough to go without. The reason for the individual mandate was that elderly people have much more expensive healthcare needs, so the government sought to subsidize their costs. Should younger generations likewise be forced to bear the lion’s share of taxation?

Obviously, we don’t want senior citizens taxed out of their homes either.

Others brought up renters, who do not directly pay property taxes. That’s technically true, but most landlords will build those taxes into the price of rent. The cost of rent has skyrocketed in recent years—as a homeowner, my mortgage is currently just over half of what I was paying as a renter a few years ago. Landlords must consider not only their own mortgages, but also property taxes, insurance, utilities, maintenance, and more, while still earning a profit to make it worthwhile. Landlords also pay income taxes on rental income and capital gains taxes if and when they sell those properties.

Ada County Commissioner Rod Beck reminded me that property values in the region have increased dramatically in recent years, which has lowered the levy rate for everyone. He also noted that although Ada County accounts for 38% of my property tax bill, the regional average is 24%. I presume the difference is because I live in Eagle—a city known for low taxes—while residents of Boise must pay much higher rates, which decreases the county’s relative share. Commissioners Beck, Ryan Davidson, and Tom Dayley have done a great job keeping taxes low, but they can’t do much about Boise’s exorbitant demands.

Another reader pointed out that some developers in Boise don’t pay property taxes because they’re building on land owned by the city. Some cursory research (I asked ChatGPT) pointed me to Boise’s affordable housing initiatives, specifically:

Boise’s Housing Investment Program includes a Housing Land Trust component, where the city retains ownership of land and leases it to developers to create affordable housing. This approach aims to ensure long-term affordability.

Developments on city-owned land may benefit from reduced property tax obligations, especially if structured through Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOTs). These are negotiated agreements where developers make agreed-upon payments instead of standard property taxes, often resulting in lower contributions than traditional tax assessments.

You can read more about these initiatives here. I’m not entirely sure how property taxes are structured in these cases, but it deserves more investigation. If some apartment complexes are paying reduced or no property taxes, then that too shifts the burden onto others.

A few responses expressed concern that increased assessments automatically mean higher taxes. That’s not exactly true. Your tax bill is calculated by dividing the total budget by all the taxable property in the district (creating the levy rate), then multiplying that by your home’s assessed value, minus your homeowner’s exemption. This means your assessed value could rise while your taxes go down, depending on what’s happening with property values across your district.

I explained it more in this video I recorded last week:

Several people suggested property taxes are unconstitutional, which is not correct. The US Constitution is silent on the issue, while the Idaho Constitution directly authorizes them. You can still make the argument that property taxes are immoral, inefficient, or even discriminatory in some way, but they are unfortunately constitutional.

In fact, one reader argued that property taxes are perhaps the form of taxation most aligned with the principles of the Founding Fathers. Remember: in the early days of our Republic, only property owners could vote in most states. Taxation was inextricably linked to the franchise. Today, that connection has been severed. Anyone over 18 with a pulse can vote (your mileage may vary on the latter), so the relationship between taxation and representation is no longer obvious.

We now live in a world where many such connections have been broken. Many who vote for higher taxes, whether by supporting school levies or electing city council members who promise new spending, aren’t the ones paying those taxes. What would our state look like if only property owners could vote in taxing district elections? Would we be wiser stewards of our own money?

In conversations over the weekend I heard multiple suggestions to eliminate taxes on homeowners entirely and shift the burden to commercial properties and second homes. That’s an interesting idea. However, I’m always cautious about the long-term consequences of carving certain groups out of responsibility for funding government. The fewer people who pay taxes, the greater the temptation to raise them, since most voters won’t feel the effects directly. After all, a government that robs Peter to pay Paul can always count on Paul’s support.

Finally, I would be remiss not to link to Fred Birnbaum’s excellent article at the Idaho Freedom Foundation from last fall which laid out a roadmap for ending property taxes via spending cuts:

How could all this have worked differently? Well just as an example, in FY23 over $300 million in sales tax revenue was provided to county and local governments. There is nothing sacrosanct about this amount. Sales taxes pulled in over $3 billion in FY23. Had less money been spent on state appropriations, some of the extra sales tax revenue could have been used to displace property taxes. But this only works if spending growth at the state, county, and local levels had been held to inflation growth plus population.

This exercise isn’t an exact policy prescription but rather a rough example to show how ambitious tax relief is possible — including eliminating an entire class of taxes if proper spending restraint had been exercised.

It will be interesting to see what Florida does in response to Gov. Ron DeSantis’ call to eliminate property taxes entirely. Let’s keep this conversation going.

Gem State Chronicle is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

About Brian Almon

Brian Almon is the Editor of the Gem State Chronicle. He also serves as Chairman of the District 14 Republican Party and is a trustee of the Eagle Public Library Board. He lives with his wife and five children in Eagle.