By Jonathan Keeperman | Originally published at Office Hours with Lomez

Note: As of this writing—bedtime, June 23rd—it appears the land sale proposal is getting pushed out of budget reconciliation because of the Byrd Rule. Good news. Nonetheless, Mike Lee assures us he will continue to pursue this issue, so this post will remain relevant for the foreseeable future.

Another policy debate has erupted on X over the last couple of weeks regarding Senator Mike Lee’s proposal to sell off between .5% and .75% of public lands across eleven western states (Montana notably excluded). The proposal, which has been shoehorned into the budget reconciliation process, has the stated aims of increasing affordable housing and helping pay down the national debt.

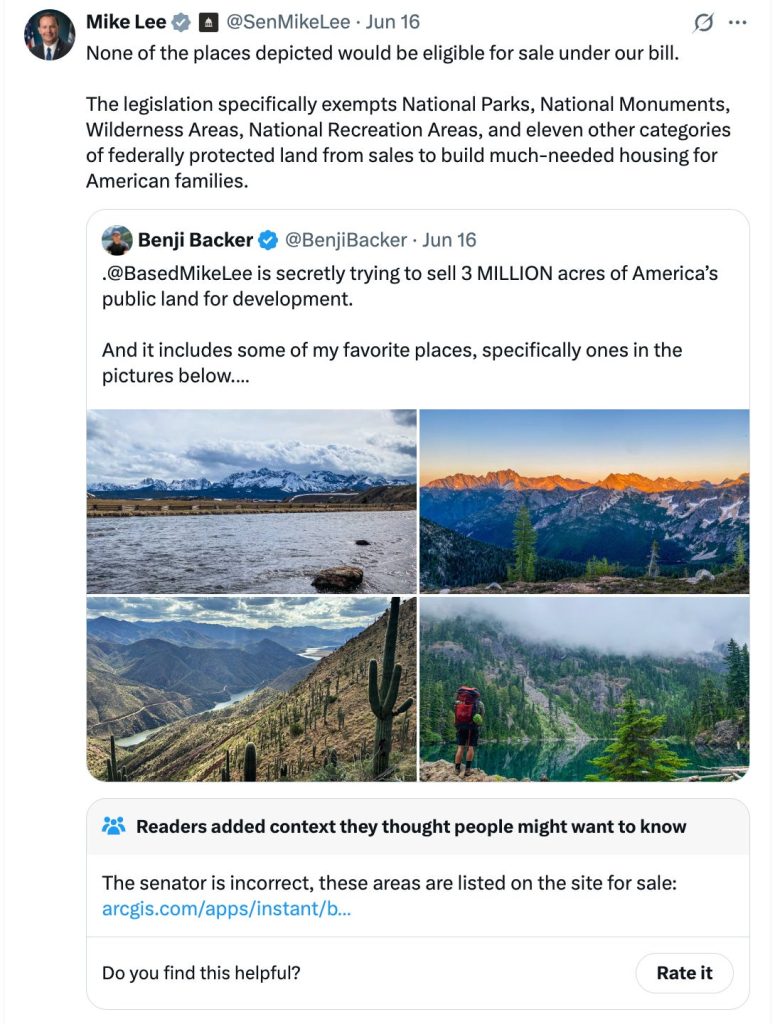

The proposal was first released on June 11th, then revised shortly thereafter with some qualifying language and additional specifications about existing mining, logging, and grazing rights, but went largely unnoticed until June 16th when Benji Backer posted the following tweet:

Lee then made the mistake of responding to the tweet stating that none of the places depicted in the images would be eligible for sale under the terms of the proposal. But he was wrong. Whoops. Turns out all of those places are eligible for sale.

Lee’s false correction, as of this writing, has racked up 4.7 million views on X, mostly from people newly aware, and very angry about the idea of our public lands, which contain much of the greatest natural beauty in the world, being sold-off for affordable housing (or any other reason, for that matter).

There have been attempts by Lee and other proponents of the bill to backtrack and clarify and point to sections of the proposal that might, in theory, narrow the scope of the sale to tracts of land bordering already existing municipalities that don’t get used much or are otherwise mismanaged or unobjectionably better suited for modest development, but these explanations have been unconvincing and have only raised more doubts about the language of the proposal and the true intentions of its backers.

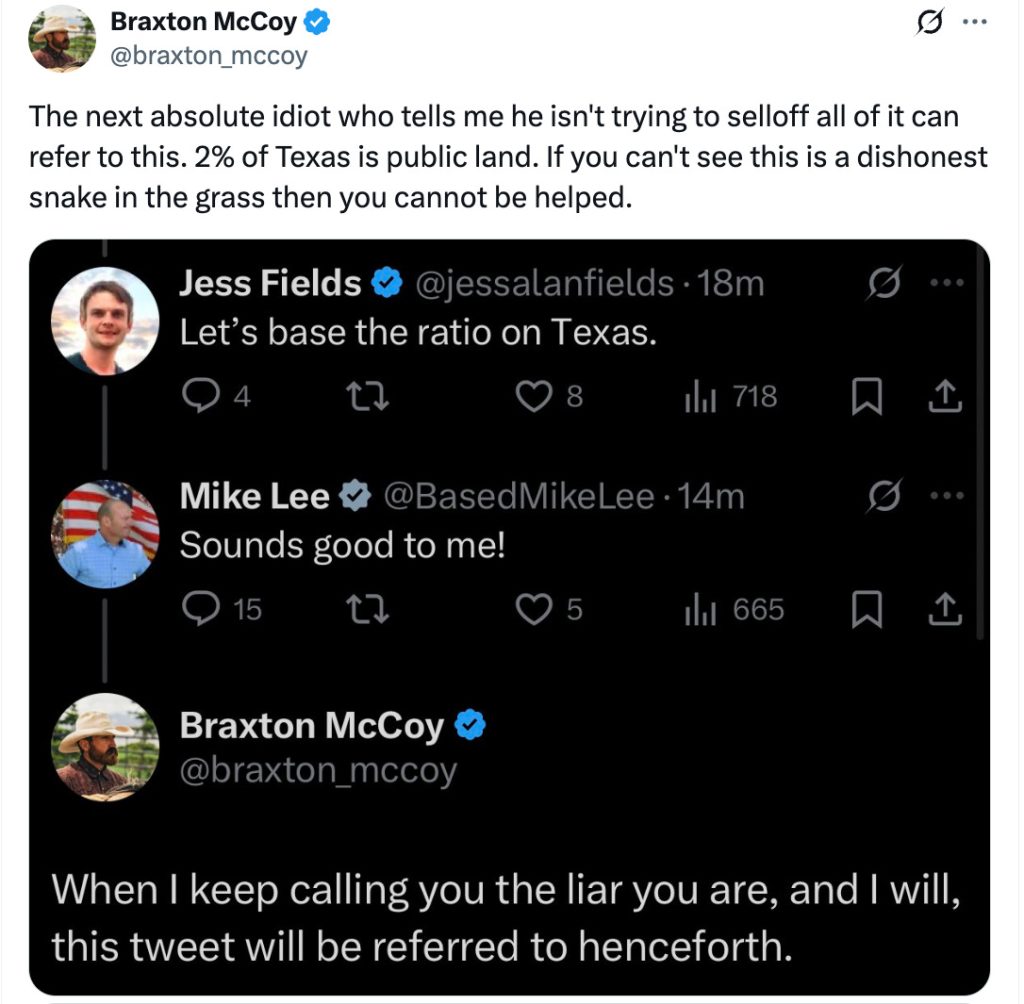

Lee, for example, despite his attempts to moderate his position, has been caught saying he hopes to sell off as much as 98% of our public lands—orders of magnitude in excess of the .75% being floated—and that he’d prefer if our public land was owned by BlackRock. I try not to put too much weight on rhetorical blunders like this, especially in the context of private DMs, but Lee’s admissions don’t exactly shore up the grave and mounting doubts the public has about this land grab.

So, okay, what exactly is at stake here? Where did this proposal to sell off public lands come from? What are “public lands” anyway? Doesn’t it make sense to reduce public land holdings, especially in the western states like Utah and Nevada where as much as 80% of the real estate is in federal hands? Does this proposal actually threaten places people fish and hunt and go camping etc. or is that just a social media fever dream? And isn’t it true that we do actually need more housing and that this proposal could help?

I will answer all of these questions and more below.

1. “People online seem to really not like the idea of selling public land. What’s the deal with that?”

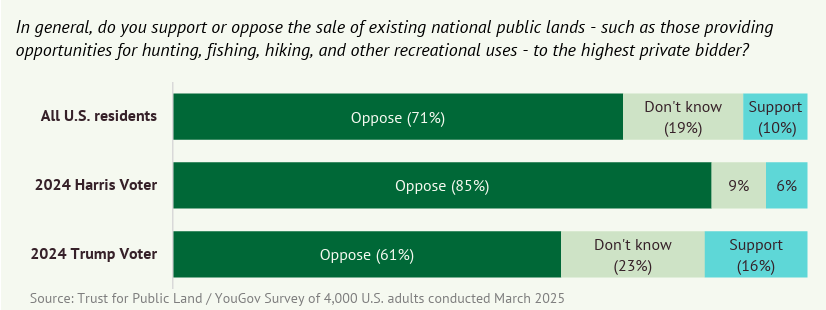

Before diving into the legal specifics or broader political context, it’s important to start with the plain descriptive fact that this proposal is wildly unpopular across the political spectrum, and even in the states where the feds control a majority of the land. Despite what Lee and his supporters insist, the vehement objections to this proposal they’ve encountered online are consistent with all available polling data on this issue.

A recent YouGov poll found that 71% of Americans oppose the sale of public lands to private interests, with just 10% in favor. This opposition is bipartisan:

- 61% of 2024 Trump voters oppose such sales (only 16% support),

- And 85% of Harris voters are opposed (just 6% support).

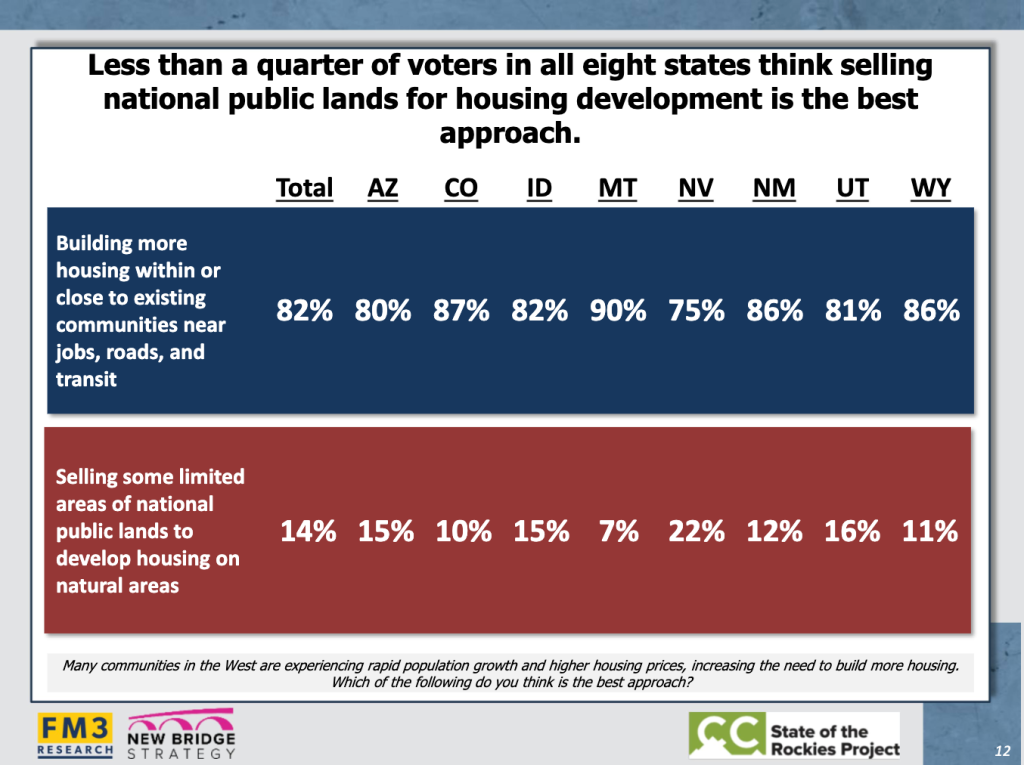

Even in the American West, where federal land holdings are vast and often seen as a mixed blessing, there is no appetite for mass privatization. According to the Colorado College State of the Rockies Project, an overwhelming 82% of Westerners prefer building more housing within or close to existing communities, rather than selling public lands for development. Only 14% support sales of public land for housing construction in natural areas. This, despite the fact that 81% also express serious concern about the rising cost of living. Even while acknowledging the problem of affordable housing, a vanishingly small number of people see this as a viable solution.

These are strongly and widely held objections that are as much intuitive as they are based on any rational evaluation of the underlying trade-offs. People really really really like their public lands. And any politician who is going to propose selling off even a small fraction of them needs to address the issue with maximum prudence and sensitivity.

This basic political reality seems entirely absent from how the proposal has been messaged and sold. Whatever else one thinks, the concept is political poison for the GOP, and if pursued more aggressively, risks inflicting serious collateral damage on the broader Trump agenda.

This is simply VERY BAD politics.

2. “Where did this very unpopular idea come from, and why now?”

The stewardship of public lands in the west is, as far as I know, a uniquely American system that relies on a Public Trust Doctrine adapted from English Common Law and precedes the settlement of the American frontier. Rodeo Professor, who has been one of the leading voices in opposition to the Lee proposal, has talked in depth about this on X. In short this means that Feds do not “own” the land in the traditional sense…

You, dear reader, own the land.

The land, and the resources it contains, are held in a trust by the government for your (our) benefit and use. The state cannot sell or alienate these resources without strong justification. The presumption is against disposal.

The key statutory framework here is the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA). Before FLPMA, federal lands were largely governed by a patchwork of 19th- and early 20th-century statutes like the Homestead Act that focused on getting the lands into the hands of private citizens and entities for the purposes of settlement, mining, logging, ranching, railroad construction, and the like.

But by the mid-20th century, the mandate had changed. Private settlement, i.e. homesteading, had largely leveled off. Pretty much any piece of land that could produce water and sustain human communities had already been claimed. The FLPMA reoriented public land priorities in light of these realities by formalizing a policy of retention for its land holdings rather than disposal. It instructed the Bureau of Land Management to manage federal lands under the doctrine of “multiple use and sustained yield.” Under this new paradigm, public lands could simultaneously be used for hunting, fishing, grazing, mining, and proactive wildlife conservation, all balanced and weighed according to public input and preference.

Importantly, FLPMA, while maintaining the current status-quo of multi-use public land, does still allow for land sales. The Secretary of the Interior can dispose of public land through sale or exchange if it meets certain criteria and serves the public interest. Yes, it is admittedly slow and procedurally constrained, and must pass through a number of assessments and reviews, but that is a feature, not a bug. It is precisely that the system is designed to discourage impulsive or large-scale sell-offs. It is designed, in other words, to prevent exactly the kind of thing being proposed by Mike Lee.

Attempts to undo this settled consensus have cropped up periodically, most notably in the Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1970s and early 80s, when Western conservatives (especially in Utah and Nevada) pushed for federal land to be ceded to state control. The movement, driven largely by a sort of rugged libertarianism that prevailed in the west—and still prevails, though to a lesser degree—was not without very legitimate grievances.

Many rural communities felt locked out of decisions that affected their local economies and ways of life. Land use plans were drawn up in distant federal offices with little local input. Grazing permits became harder to obtain or more costly. Logging operations faced mounting restrictions. The pace and tone of federal environmental regulation changed dramatically in the wake of the 1960s and early 70s, mostly on account of what many saw as draconian restrictions imposed by the newly crafted EPA and the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the political right, for good measure, took up public land reform as a minor cause.

But this was a different time, without our current demographic pressures weighing down on western states and without the specter of multi-national REITs or foreign governments licking their chops at the idea of buying out America’s crown jewel. And even then, the idea of selling off these lands proved too politically risky, and Reagan was forced to abandon the issue.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, most serious land reform efforts were narrowly focused on land swaps and easements and occasional pilot programs like the Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act (1998), which allowed for limited sales of BLM land around Las Vegas, with proceeds reinvested in local conservation and development. These were slow, technical processes with a narrow scope and usually strong local support. They worked and should be regarded as templates for future efforts.

Over the past decade, especially since the Bundy standoff in 2014 and the Malheur occupation in 2016, land privatization has resurfaced as a political flashpoint. More recently—and in a case some suspect helped spur Lee’s proposal—the issue of public access came to a head in Wyoming over the legality of corner crossings when four hunters used a custom ladder to cross between BLM parcels in a checkerboard section of Elk Mountain Ranch owned by North Carolina pharmaceutical executive Fred Eshelman. Earlier this year, the hunters finally prevailed in federal appeals court, much to the dismay of big private land owners, but the episode has once again raised the question over the use and access to public lands.

It’s an issue that is not going away, and is deeply rooted in a long history of contestation and compromise, with high sensitivities on all sides, making it all the more surprising (and concerning) that Lee would choose the occasion of a budget reconciliation process to jam through the largest reduction of the public domain in the country’s history.

3. “Okay, that’s great and all but what about this specific proposal? I saw a thread from [Serious Online Pundit Man] that Mike Lee’s bill was actually good and the concerns of people like you and other random X users are unfounded.”

Wrong.

One of the more frustrating aspects of this debate has been the widespread insistence—often made with great confidence—that the bill contains ample safeguards and restrictions to prevent abuse and that anyone objecting to its forced inclusion in the reconciliation process is either illiterate, astroturfed, or otherwise opposed to its stated goals. The defenders insist, “It’s only 0.5%. It only affects land near cities. It’s up to local governments. There are protections for wildlife and recreation. The Secretary has to consider infrastructure, affordability, housing. BlackRock can’t buy it. China can’t buy it. Calm down!”

Let’s take a closer look:

Claim 1: “It’s only 0.5% of public land. This is a small, cautious pilot program.”

Not exactly. The bill requires the identification and disposal of not less than 0.5% and not more than 0.75% of BLM and National Forest land. That means somewhere between 2,000,000 and 3,000,000 acres, depending on how the numbers are run. There’s no upper limit on concentration in a given area, and the Secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture are required to dispose of all land selected within five years. So, even if there is some amount of unobjectionably useful land that satisfies the stated requirements of the bill (more on that in a bit), the disposal requirements potentially put highly valued acreage at risk if the initial sell-off falls short of the minimum requirement.

Are there 2 million acres of developable land that don’t run afoul of the constraints the bill’s proponents insist exist? Maybe. The problem is we have no idea. No one has taken the time to actually figure this out, or worse, they have figured it out and that’s why they won’t show us the map.

Claim 2: “The bill prohibits the sale of ecologically or recreationally sensitive land. If you are a hunter, fisherman, hiker, etc. you have nothing to worry about.”

False, egregiously so. The only land explicitly excluded from sale is what the bill defines as “federally protected land,” a term that includes national parks, wilderness areas, historic sites, and designated recreation areas, but which designation is actually quite narrow and doesn’t even begin to encompass the totality of national forest and BLM land that is enjoyed by millions of recreationalists.

As I’ve said elsewhere, this is one of those sneaky rhetorical sleights of hand that proponents of the proposal expect most people to overlook. It is either intentionally deceitful and should call their true motivations into question, or else an indication of their own ignorance of what these designations mean and should make you doubly concerned that the very people who authored the proposal do not understand its consequences.

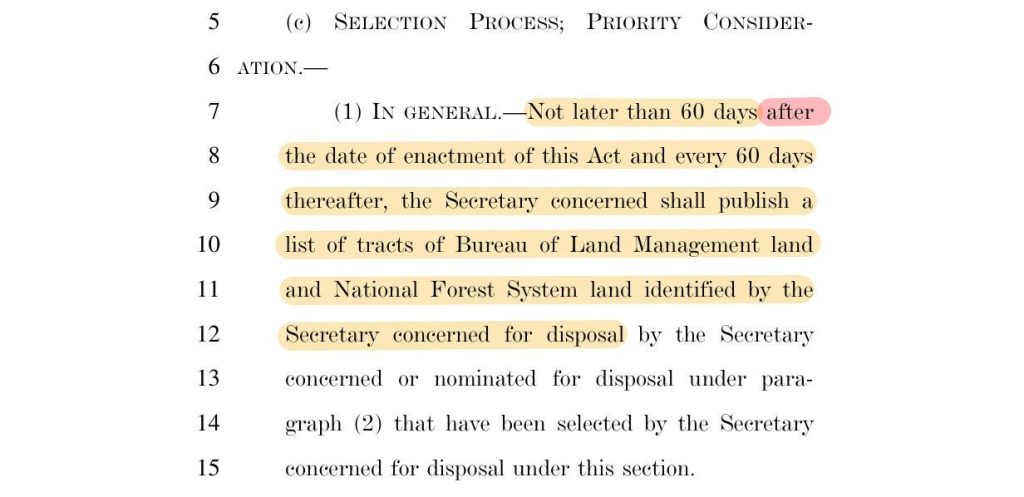

In any event, we can’t know what land will or will not be sold, because the people who drafted the bill have designed it so that the parcels being auctioned off will only be made available to the public 60 days after the bill has passed.

Claim 3: “The bill requires state and local consultation, so the process will be democratic and accountable.”

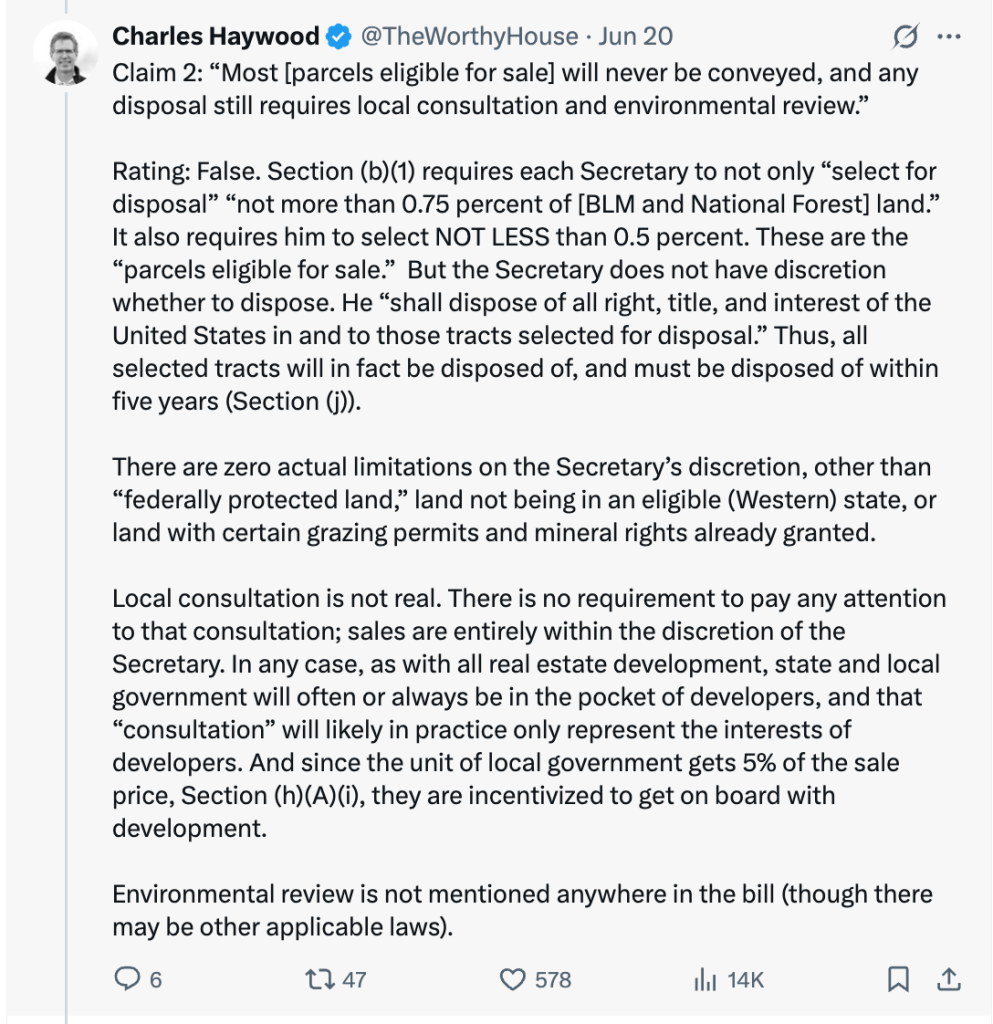

If you believe this, I have a bridge to sell you. The bill requires that the Secretaries consult with state, tribal, and local governments, yes, but it imposes no requirement that those entities approve the selection or sale of the land. Consultation does not equal consent and is bound by nothing. Nor does the bill require the Secretary to document the outcomes of those consultations or respond to any objections raised. There is no meaningful check on agency discretion. As Charles Haywood points out (as part of a long point-by-point rebuttal of Mike Lee’s claims that is well worth your time), the incentives for local governments to go along with the sales are strong—they receive 5% of the proceeds—and the political pressure from developers in many of these communities will be immense.

Even setting aside the weak definition of consultation, the idea that local governments will be meaningful competitors in land acquisition is mostly fantasy. Most of these municipalities don’t have the cash on hand to buy up parcels at “fair market value,” as the bill requires. They operate on lean budgets, often constrained by state-level tax caps or bonding restrictions, and are unlikely to even enter, let alone win a bidding war with private equity firms or development syndicates. There is no provision in the bill for preferential pricing, no earmarked funds for local purchases, or anything like that that might ensure meaningful public acquisition of high-value parcels. The “right of first refusal” is worthless if you can’t afford to make an offer.

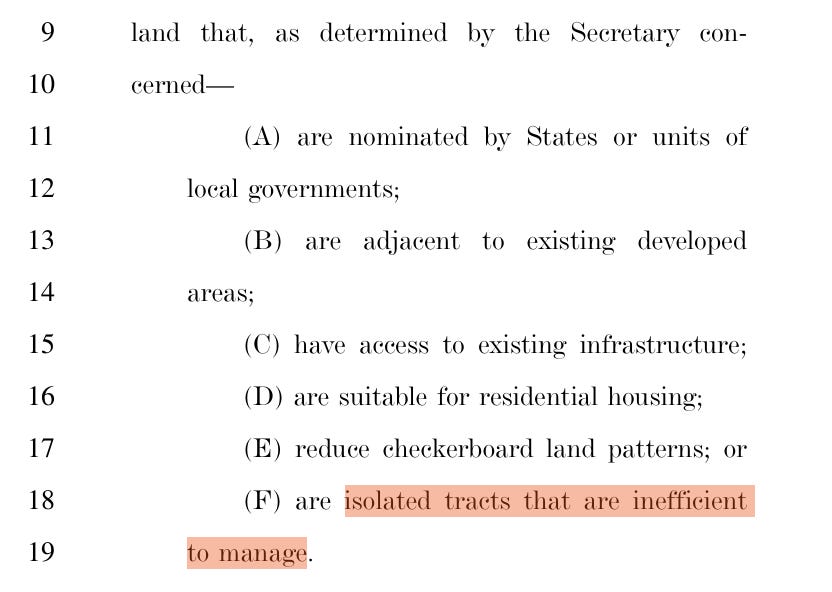

Claim 4: “Only land near cities and existing infrastructure can be sold.”

Also false and suspiciously misleading. The bill does not require that land be near existing infrastructure. It says only that “priority consideration” may be given to land that is adjacent to developed areas or has access to infrastructure. That language is non-binding. There is no requirement to exclude remote parcels. In fact, the same section explicitly gives priority to “isolated tracts that are inefficient to manage,” which is bureaucratic code for backcountry land that could be sold off without too much administrative headache. If the Secretary decides to sell land far from any road or sewer line, there is nothing in the bill to stop him.

This, truthfully, isn’t a problem in and of itself. In principle there is nothing wrong with selling land that is far more remote. But again, it’s indicative of the larger incoherence of this proposal, and/or the attempt to sneak through allowances that circumvent what’s being publicly stated about the bill’s parameters.

Claim 5: “Sales are limited to small buyers. BlackRock/China/Bill Gates/[choose your globalist boogeyman] can’t buy it all.”

False. The bill limits any individual sale to two tracts per buyer. But it imposes no limits on the number of total tracts any one entity can acquire over time, through multiple sales, through shell companies, or through agents. Nothing in the bill prevents a large institutional investor from structuring purchases in such a way that it accumulates massive holdings while remaining technically compliant. Anyone familiar with the way real estate is transacted in this country knows how easily this kind of rule can be gamed.

It’s frankly insulting—and also deeply suspicious—that proponents of the bill regard any of this language as being restrictive enough to prevent these kinds of purchases.

Do they actually believe that?

Claim 6: “The land has to be used for housing, so this will help address affordability.”

This is perhaps the most deceptive claim of all. The bill requires that the buyer submit a “statement of planned use” including how the land will address local housing needs, but the Secretary is under no obligation to weigh that information when selecting buyers. The land must, on paper, be used for “housing or associated community needs,” but that restriction is so vague (“associated community needs”… what does that mean?) and ultimately unenforceable, that it’s meaningless. To make matters worse, the restriction expires after ten years, at which point the landowner can do whatever they want. There is nothing here to ensure that any of this actually leads to affordable housing or serves the public good.

In summary, the bill contains no hard limits, no meaningful oversight, no enforceable restrictions, and no durable public-interest guarantees. Every supposed safeguard is either discretionary or easily circumvented. It might appear cautious, and might even offer its proponents some plausible deniability if/when these deals end up producing high-end vacation condos or bridging private ranches to cut-off access points to cherished hunting grounds, but it leaves open the door for every single abuse its opponents care about. And perhaps most tellingly, its authors refuse to produce even a simple map of which parcels might be sold or which tracts exist outside these supposed restrictions. Why not?

One wonders.

4. “Got it. Fine. But we need more housing. Cities in Utah and Nevada are filled to the brim, and the rest of the west has become unaffordable for young people. Can’t we do something about that?”

Yes. In fact, we can do many things about that. But selling off millions of acres of public land through a rushed and politically toxic reconciliation bill is somewhere in the range of 10 to 20 millionth on the list of best ideas.

If you want to reduce housing pressure, start by reducing demand. Burning political capital on land sales (unpopular) versus accruing political capital on deportations (very popular) is a no-brainer first step for anyone taking this issue seriously.

Here is a detailed look at the specific effects of illegal immigration on housing. In short, the surge in illegal immigration since 2021—amounting to an increase of 6.6 million people (minimum) and 2.4 million new immigrant-headed households—has significantly intensified demand for housing, particularly in high-immigration regions like the major cities in western states. Estimates point to a roughly 12% increase in home prices and rentals from illegal immigration.

Do you really care about increasing affordable housing supply? Okay. Then do something about that.

It’s also the case that we have cities around the country—Detroit and St. Louis come to mind—with massive reverses of unused housing stock that remain vacant for socio-political reasons we’re not allowed to talk about. These cities were built for populations significantly larger than they currently hold and under conditions of sufficient political will can quite quickly be converted into their former glory. Detroit, for instance, once home to nearly 2 million people, now houses fewer than 630,000. The city has an estimated 80,000 vacant buildings and tens of thousands more empty lots. St. Louis has more than 25,000 vacant properties. These already-built homes for young families come with the added bonus of intact plumbing, streets with sewer and electrical lines, schools, libraries, parks, little league fields, and commercial infrastructure.

I have a hard time taking any affordable housing advocate seriously who doesn’t address this problem. Some might say that cities are fertility shredders, and in recent generations this might be correct, but it’s not because cities, which for all of modernity supported family formation, suddenly, by virtue of being cities, somehow, by some logic of density or upward mobility or whatever, ceased to become livable for parents and their kids. Cities can—and should—support more people and more families, and for politicians who want to demonstrate real courage and real forward thinking on this issue, revitalization of our once great cities should be a central focus.

5. “So is there any way to get meaningful land reform out west that better balances state and local control of their own backyards with the interests of public land enjoyers?”

Yes. But it’s going to require a very different legislative approach and very different tone than the one adopted by Mike Lee and his allies.

To reiterate an item from above, we already have a process in the FLPMA for reviewing and disposing of federal lands. If there are areas where FLPMA is too slow or cumbersome, then make that the starting point for reform. This might mean expanding the eligibility criteria, or expedited sales for lands adjacent to municipal boundaries, or including robust claw-back provisions so speculative holdings for mining or unused land get auctioned off, or ten other targeted revisions that help the feds off-load mismanaged land to states and private actors who can better make use of them.

In other words, draft a real bill instead of trying to ram the largest sell-off of public lands in American history in the middle of a budget reconciliation process, without public hearings or maps, and absent any attempt to take seriously the complaints of a public that OVERWHELMINGLY opposes the entire concept.

Please, Mike Lee, if you or one of your surrogates is reading this, try to understand the emotional and spiritual gravity of this issue. For many Americans, myself included, our public lands are as central to our way of life and civic self-understanding as just about anything else. Our public lands, and the unsettled frontier they represent are, as Malmesbury Man put it, “…to the American spirit what the Royal Family is to the English, it’s the saying of mass in the Vatican to Catholics, it’s the Hajj to Muslims, it’s the Chrysanthemum Throne to Japanese. Without it, America is over.”

Such heady notions are rarely worthy of the political trenches on X, but when it comes to the vast expanses of our western lands we’ll allow such indulgences.

This proposal is treading on sacred ground. This is not something to be done lightly, and there is absolutely no reason to rush it. God has warned us before about making mistakes like this. Take heed.

About Jonathan Keeperman

Jonathan Keeperman is the founder and managing editor of Passage Press. Follow him on X @L0m3z.